Korean J healthc assoc Infect Control Prev.

2017 Jun;22(1):1-8. 10.14192/kjhaicp.2017.22.1.1.

Recurrent Burkholderia cepacia Pseudo-bacteremia Related to Contaminated Commercial Product of 0.5% Chlorhexidine Solution

- Affiliations

-

- 1Infection Control Office, Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. hswon1@snu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2416033

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14192/kjhaicp.2017.22.1.1

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Burkholderia cepacia is one of the key pathogens involved in the nosocomial outbreaks via contaminated supplies. We describe here an experience of recurrent B. cepacia pseudo-bacteremia caused by the contaminated commercial product of 0.5% chlorhexidine solution in a hospital.

METHODS

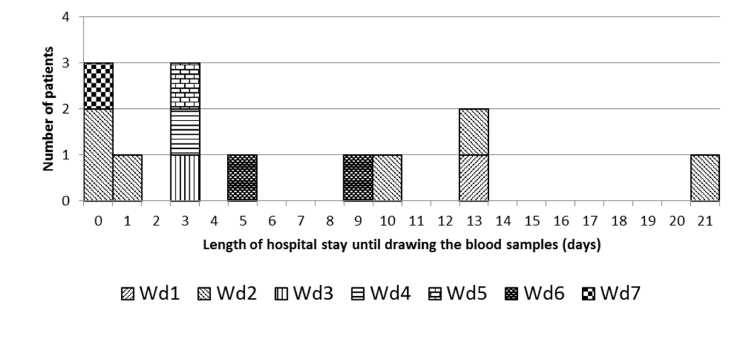

B. cepacia bacteremias detected from 30 November to 17 December 2014 were defined as cases. Epidemiological data were collected by reviewing the medical records and interviews with the healthcare workers. Suspected antiseptics were cultured using blood culture media.

RESULTS

Using regular active surveillance of microbiological results, 15 B. cepacia isolates were found in 13 patients. Pseudo-bacteremia was suspected in all of the cases based on the clinical analysis of individual patients. Misuse of 0.5% chlorhexidine in its solution rather than its tincture form as a skin antiseptic prior to drawing blood for blood culture procedures was the only identifiable risk factor for B. cepacia pseudo-bacteremia. Culture of 0.5% chlorhexidine solution was negative. Suspending the use of 0.5% chlorhexidine solution and educating healthcare workers on the proper use of the antiseptic ended the outbreak.

CONCLUSION

Regular surveillance of unusual pathogens may lead to early detection of nosocomial outbreaks. Epidemiological analysis is a strong indicator for the source of outbreak even when there is no microbiological evidence of contamination source.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Mangram A, Jarvis WR. Nosocomial Burkholderia cepacia outbreaks and pseudo-outbreaks. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996; 17:718–720.

Article2. Romero-Gómez MP, Quiles-Melero MI, Peña García P, Gutiérrez Altes A, García de, Jiménez C, et al. Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bacteremia caused by contaminated chlorhexidine in a hemodialysis unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008; 29:377–378.

Article3. Lee CS, Lee HB, Cho YG, Park JH, Lee HS. Hospital-acquired Burkholderia cepacia infection related to contaminated benzalkonium chloride. J Hosp Infect. 2008; 68:280–282.

Article4. Nasser RM, Rahi AC, Haddad MF, Daoud Z, Irani-Hakime N, Almawi WY. Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bacteremia traced to contaminated hospital water used for dilution of an alcohol skin antiseptic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004; 25:231–239.

Article5. Panlilio AL, Beck-Sague CM, Siegel JD, Anderson RL, Yetts SY, Clark NC, et al. Infections and pseudoinfections due to povidone-iodine solution contaminated with Pseudomonas cepacia. Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 14:1078–1083.

Article6. Ko S, An HS, Bang JH, Park SW. An outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia complex pseudobacteremia associated with intrinsically contaminated commercial 0.5% chlorhexidine solution. Am J Infect Control. 2015; 43:266–268.

Article7. Moehring RW, Lewis SS, Isaacs PJ, Schell WA, Thomann WR, Althaus MM, et al. Outbreak of bacteremia due to Burkholderia contaminans linked to intravenous fentanyl from an institu tional compounding pharmacy. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174:606–612.

Article8. Jumaa PA, Chattopadhyay B. Pseudobacteraemia. J Hosp Infect. 1994; 27:167–177.

Article9. Ben-Ari J, Wolach O, Gavrieli R, Wolach B. Infections associated with chronic granulomatous disease: linking genetics to phenotypic expression. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012; 10:881–894.

Article10. George RB, Cartier Y, Casson AG, Hernandez P. Suppurative mediastinitis secondary to Burkholderia cepacia in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Can Respir J. 2006; 13:215–218.

Article11. Mann T, Ben-David D, Zlotkin A, Shachar D, Keller N, Toren A, et al. An outbreak of Burkholderia cenocepacia bacteremia in immunocompromised oncology patients. Infection. 2010; 38:187–194.

Article12. Yamagishi Y, Fujita J, Takigawa K, Negayama K, Nakazawa T, Takahara J. Clinical features of Pseudomonas cepacia pneumonia in an epidemic among immunocompromised patients. Chest. 1993; 103:1706–1709.

Article13. Irwin AE, Price CS. More than skin deep: moisturizing body milk and Burkholderia cepacia. Crit Care. 2008; 12:115.14. Lu DC, Chang SC, Chen YC, Luh KT, Lee CY, Hsieh WC. Burkholderia cepacia bacteremia: a retrospective analysis of 70 episodes. J Formos Med Assoc. 1997; 96:972–978.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pseudoinfections Due to Benzalconium-chloride Solution Contaminated with Burkholderia cepacia

- Microbial Contamination of 0.05% Chlorhexidine Gluconate Solution

- A Case of Burkholderia cepacia Bacteremia and Infective Spondylitis, Treated with Ceftazidime and Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Combination Therapy, which did not Respond to Carbapenem Monotherapy

- Two Cases of Skin Infection with Burkholderia cepacia

- Vertebral Osteomyelitis caused by Burkholderia cepacia in an Immunocompetent Elderly Patient After Acupuncture