J Gastric Cancer.

2018 Jun;18(2):118-133. 10.5230/jgc.2018.18.e12.

Feasibility and Effects of a Postoperative Recovery Exercise Program Developed Specifically for Gastric Cancer Patients (PREP-GC) Undergoing Minimally Invasive Gastrectomy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Surgery, Graduate School, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. wjhyung@yuhs.ac

- 2Department of Surgery, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon, Korea.

- 3Exercise Physiology Laboratory, Kookmin University, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Medi Plus Solution, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Biostatistics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 7Gastric Cancer Center, Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Sports, Health, and Rehabilitation Major, Kookmin University, Seoul, Korea.

- 9Robot and MIS Center, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2414532

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5230/jgc.2018.18.e12

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Exercise intervention after surgery has been found to improve physical fitness and quality of life (QOL). The purpose of this study was to investigate the feasibility and effects of a postoperative recovery exercise program developed specifically for gastric cancer patients (PREP-GC) undergoing minimally invasive gastrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

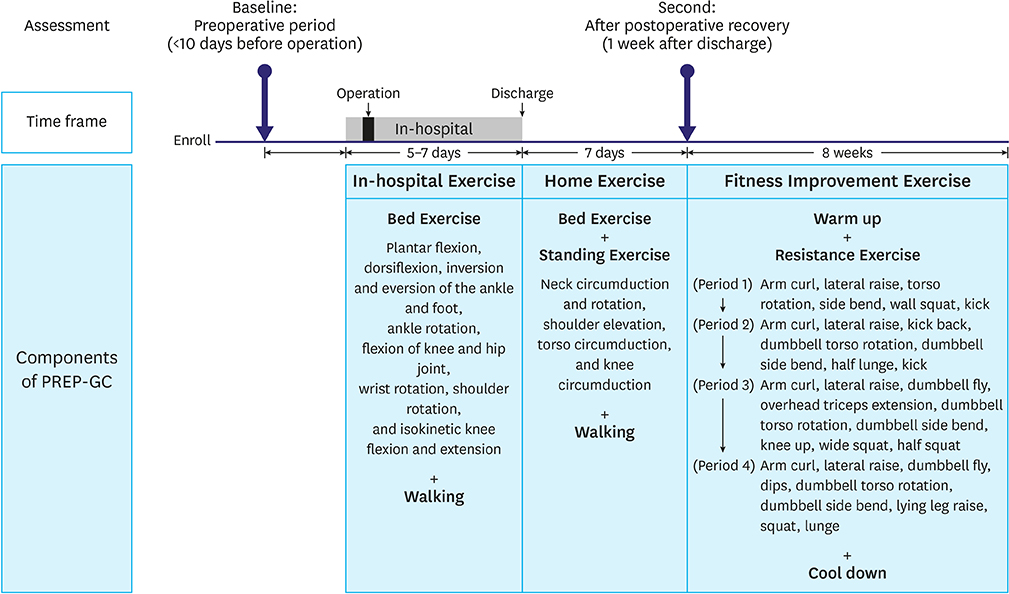

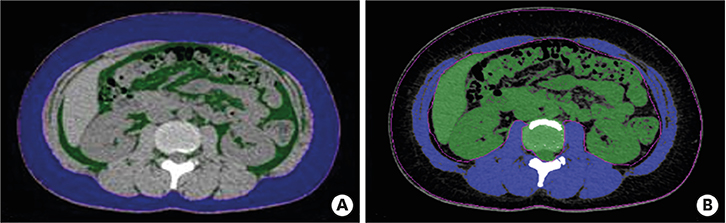

Twenty-four patients treated surgically for early gastric cancer were enrolled in the PREP-GC. The exercise program comprised sessions of In-hospital Exercise (1 week), Home Exercise (1 week), and Fitness Improvement Exercise (8 weeks). Adherence and compliance to PREP-GC were evaluated. In addition, body composition, physical fitness, and QOL were assessed during the preoperative period, after the postoperative recovery (2 weeks after surgery), and upon completing the PREP-GC (10 weeks after surgery).

RESULTS

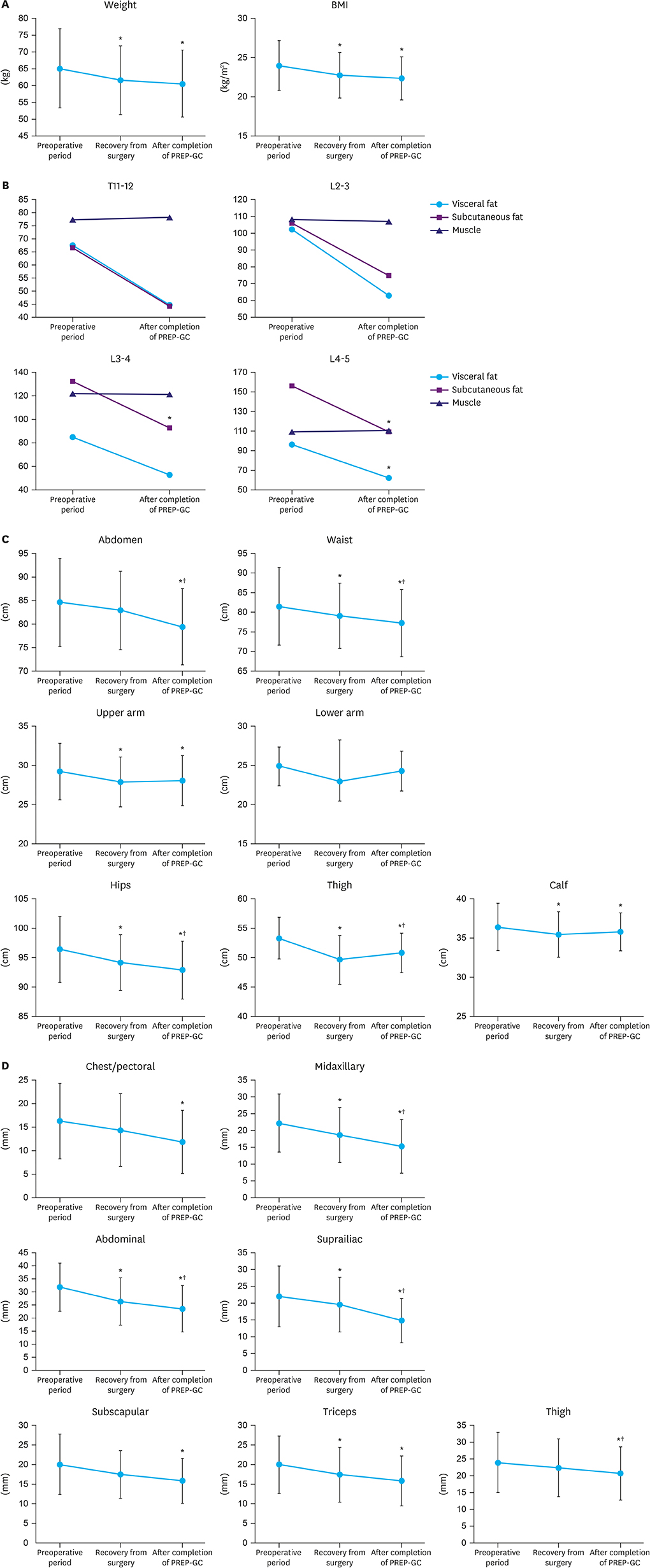

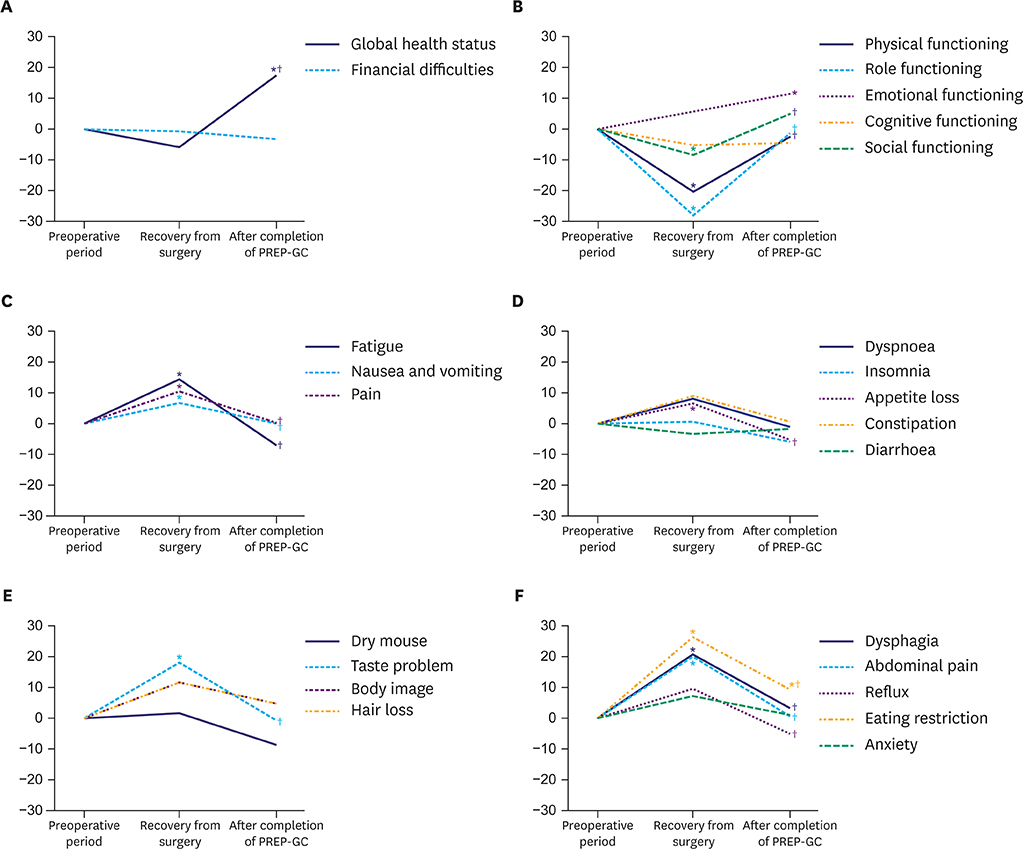

Of the 24 enrolled patients, 20 completed the study without any adverse events related to the PREP-GC. Adherence and compliance rates to the Fitness Improvement Exercise were 79.4% and 99.4%, respectively. Upon completing the PREP-GC, patients also exhibited restored cardiopulmonary function and muscular strength, with improved muscular endurance and flexibility (P < 0.05). Compared to those in the preoperative period, no differences were found in symptom scale scores measured using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) and Quality of Life Questionnaire-Stomach Cancer-Specific Module (QLQ-STO22); however, higher scores for global health status and emotional functioning were observed after completing the PREP-GC (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

In gastric cancer patients undergoing minimally invasive gastrectomy, PREP-GC was found to be feasible and safe, with high adherence and compliance. Although randomized studies evaluating the benefits of exercise intervention during postoperative recovery are needed, surgeons should encourage patients to participate in systematic exercise intervention programs in the early postoperative period (Registered at the ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01751880).

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lee JH, Kim KM, Cheong JH, Noh SH. Current management and future strategies of gastric cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2012; 53:248–257.

Article2. Akoh JA, Macintyre IM. Improving survival in gastric cancer: review of 5-year survival rates in English language publications from 1970. Br J Surg. 1992; 79:293–299.

Article3. Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Field CJ, Fairey AS. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:1660–1668.

Article4. Sellar CM, Bell GJ, Haennel RG, Au HJ, Chua N, Courneya KS. Feasibility and efficacy of a 12-week supervised exercise intervention for colorectal cancer survivors. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014; 39:715–723.

Article5. Zopf EM, Bloch W, Machtens S, Zumbe J, Rubben H, Marschner S, et al. Effects of a 15-month supervised exercise program on physical and psychological outcomes in prostate cancer patients following prostatectomy: the prorehab study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015; 14:409–418.6. Streckmann F, Kneis S, Leifert JA, Baumann FT, Kleber M, Ihorst G, et al. Exercise program improves therapy-related side-effects and quality of life in lymphoma patients undergoing therapy. Ann Oncol. 2014; 25:493–499.

Article7. van Waart H, Stuiver MM, van Harten WH, Geleijn E, Kieffer JM, Buffart LM, et al. Effect of low-intensity physical activity and moderate- to high-intensity physical exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy on physical fitness, fatigue, and chemotherapy completion rates: results of the PACES randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:1918–1927.

Article8. Broderick JM, Guinan E, Kennedy MJ, Hollywood D, Courneya KS, Culos-Reed SN, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a supervised exercise intervention in de-conditioned cancer survivors during the early survivorship phase: the PEACH trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2013; 7:551–562.

Article9. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2011; 14:101–112.10. O'Sullivan SB. Perceived exertion. A review. Phys Ther. 1984; 64:343–346.11. Thompson WR, Gordon NF, Pescatello LS. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2010.12. Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Gettman LR. Intertester reliability of selected skinfold and circumference measurements and percent fat estimates. Res Q. 1978; 49:546–551.

Article13. American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009; 41:687–708.14. Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999; 70:113–119.15. Escamilla RF, Zheng N, Imamura R, Macleod TD, Edwards WB, Hreljac A, et al. Cruciate ligament force during the wall squat and the one-leg squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009; 41:408–417.

Article16. Chen CH, Ho C, Huang YZ, Hung TT. Hand-grip strength is a simple and effective outcome predictor in esophageal cancer following esophagectomy with reconstruction: a prospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011; 6:98.

Article17. Fayers P, Bottomley A. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Quality of Life Unit. Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002; 38:Suppl 4. S125–S133.18. Yun YH, Park YS, Lee ES, Bang SM, Heo DS, Park SY, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2004; 13:863–868.

Article19. Fayers PM, Aronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer;2001.20. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004; 240:205–213.21. Campo RA, Agarwal N, LaStayo PC, O'Connor K, Pappas L, Boucher KM, et al. Levels of fatigue and distress in senior prostate cancer survivors enrolled in a 12-week randomized controlled trial of Qigong. J Cancer Surviv. 2014; 8:60–69.

Article22. Jensen W, Baumann FT, Stein A, Bloch W, Bokemeyer C, de Wit M, et al. Exercise training in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2014; 22:1797–1806.

Article23. Spence RR, Heesch KC, Brown WJ. Exercise and cancer rehabilitation: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010; 36:185–194.

Article24. Son T, Kwon IG, Hyung WJ. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer treatment: current status and future perspectives. Gut Liver. 2014; 8:229–236.

Article25. Blair SN, Kohl HW 3rd, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Clark DG, Cooper KH, Gibbons LW. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989; 262:2395–2401.

Article26. Abdiev S, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Ohashi N, et al. Nutritional recovery after open and laparoscopic gastrectomies. Gastric Cancer. 2011; 14:144–149.

Article27. Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008; 248:721–727.28. Aoyama T, Kawabe T, Hirohito F, Hayashi T, Yamada T, Tsuchida K, et al. Body composition analysis within 1 month after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016; 19:645–650.29. Misawa K, Fujiwara M, Ando M, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Ito Y, et al. Long-term quality of life after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective multi-institutional comparative trial. Gastric Cancer. 2015; 18:417–425.

Article30. Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, et al. Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg. 2012; 256:1008–1013.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer

- Which patients with gastric cancer should be candidates for Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols?

- Laparoscopic Surgery for Early Gastric Cancer

- Risk Factors for the Severity of Complications in Minimally Invasive Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: a Retrospective Cohort Study

- Recent Advances in Sentinel Node Navigation Surgery for Early Gastric Cancer