J Gynecol Oncol.

2017 Nov;28(6):e76. 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e76.

Assessing the effect of guideline introduction on clinical practice and outcome in patients with endometrial cancer in Japan: a project of the Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) guideline evaluation committee

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan. s.shigeta@med.tohoku.ac.jp

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine, Yamagata, Japan.

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara, Japan.

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kumamoto University Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto, Japan.

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kawasaki Medical School, Kurashiki, Japan.

- 6Clinical Research, Innovation and Education Center, Tohoku University Hospital, Sendai, Japan.

- 7Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

- 8Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dokkyo Medical University, Tochigi, Japan.

- KMID: 2413202

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e76

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

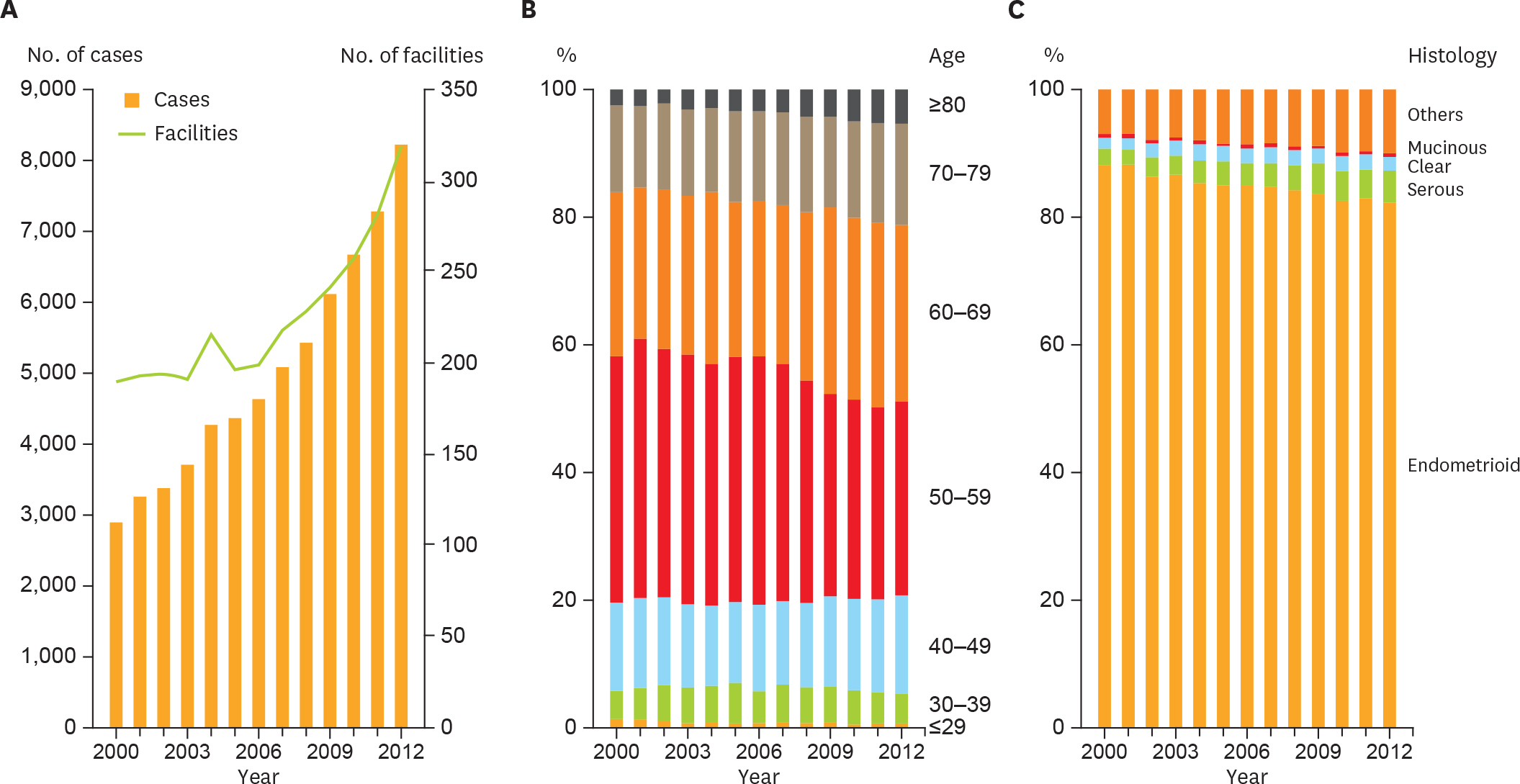

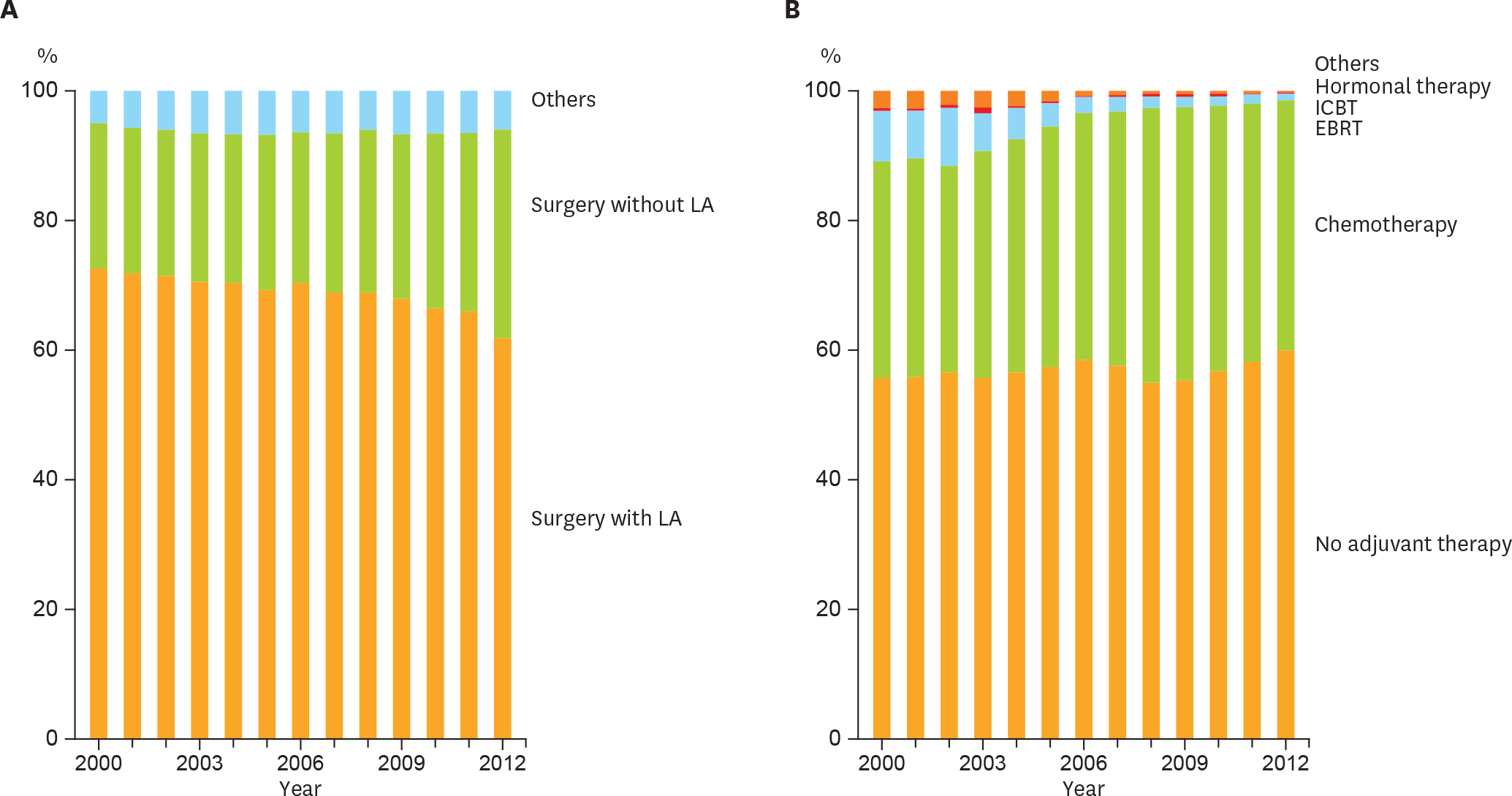

The Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) published the first practice guideline for endometrial cancer in 2006. The JSGO guideline evaluation committee assessed the effect of this guideline introduction on clinical practice and patient outcome using data provided by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) cancer registration system.

METHODS

Data of patients with endometrial cancer registered between 2000 and 2012 were analyzed, and epidemiological and clinical trends were assessed. The influence of guideline introduction on survival was determined by analyzing data of patients registered between 2004 and 2009 using competing risk model.

RESULTS

In total, 65,241 cases of endometrial cancer were registered. Total number of patients registered each year increased about 3 times in the analyzed period, and the proportion of older patients with type II endometrial cancer rapidly increased. The frequency of lymphadenectomy had decreased not only among the low-recurrence risk group but also among the intermediate- or high-recurrence risk group. Adjuvant therapy was integrated into chemotherapy (p<0.001). Overall survival did not significantly differ before and after the guideline introduction (hazard ratio [HR]=0.891; p=0.160). Additional analyses revealed patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy showed better prognosis than those receiving adjuvant radiation therapy when limited to stage I or II (HR= 0.598; p=0.003).

CONCLUSION

It was suggested that guideline introduction influenced the management of endometrial cancer at several aspects. Better organized information and continuous evaluation are necessary to understand the causal relationship between the guideline and patient outcome.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adenocarcinoma, Clear Cell/pathology/*therapy

Adult

Aged

Aged, 80 and over

Carcinoma, Endometrioid/pathology/*therapy

Chemotherapy, Adjuvant/utilization

Endometrial Neoplasms/pathology/*therapy

Female

Humans

Hysterectomy

Japan

Lymph Node Excision/utilization

Middle Aged

Multivariate Analysis

Neoplasm Staging

Neoplasms, Cystic, Mucinous, and Serous/pathology/*therapy

Outcome Assessment (Health Care)

*Practice Guidelines as Topic

Practice Patterns, Physicians'/*statistics & numerical data

Prognosis

Proportional Hazards Models

Radiotherapy, Adjuvant/utilization

*Registries

Retrospective Studies

Survival Rate

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Impact of lymphadenectomy on the treatment of endometrial cancer using data from the JSOG cancer registry

Keiko Saotome, Wataru Yamagami, Hiroko Machida, Yasuhiko Ebina, Yoichi Kobayashi, Tsutomu Tabata, Masanori Kaneuchi, Satoru Nagase, Takayuki Enomoto, Daisuke Aoki, Mikio Mikami

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(1):80-89. doi: 10.5468/ogs.20186.

Reference

-

References

1. Ushijima K. Current status of gynecologic cancer in Japan. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009; 20:67–71.

Article2. Hori M, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katanoda K, Sobue T, Nishimoto H, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2009: a study of 32 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015; 45:884–91.

Article3. Nagase S, Katabuchi H, Hiura M, Sakuragi N, Aoki Y, Kigawa J, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treatment of uterine body neoplasm in Japan: Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) 2009 edition. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010; 15:531–42.

Article4. Ebina Y, Katabuchi H, Mikami M, Nagase S, Yaegashi N, Udagawa Y, et al. Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology guidelines 2013 for the treatment of uterine body neoplasms. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016; 21:419–34.

Article5. McCluggage WG. Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol. 2002; 55:321–5.

Article6. Prat J. FIGO staging for uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009; 104:177–8.

Article7. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999; 94:496–509.

Article8. Shepherd JH. Revised FIGO staging for gynaecological cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989; 96:889–92.

Article9. Creasman W. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009; 105:109.

Article10. Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, Abu-Rustum N, Darai E. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2016; 387:1094–108.

Article11. Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983; 15:10–7.

Article12. Brinton LA, Felix AS, McMeekin DS, Creasman WT, Sherman ME, Mutch D, et al. Etiologic heterogeneity in endometrial cancer: evidence from a Gynecologic Oncology Group trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 129:277–84.

Article13. Cragun JM, Havrilesky LJ, Calingaert B, Synan I, Secord AA, Soper JT, et al. Retrospective analysis of selective lymphadenectomy in apparent early-stage endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:3668–75.

Article14. Candiani GB, Belloni C, Maggi R, Colombo G, Frigoli A, Carinelli SG. Evaluation of different surgical approaches in the treatment of endometrial cancer at FIGO stage I. Gynecol Oncol. 1990; 37:6–8.

Article15. Trimble EL, Kosary C, Park RC. Lymph node sampling and survival in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1998; 71:340–3.

Article16. Bar-Am A, Ron IG, Kuperminc M, Gal I, Jaffa A, Kovner F, et al. The role of routine pelvic lymph node sampling in patients with stage I endometrial carcinoma: second thoughts. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998; 77:347–50.

Article17. Sartori E, Gadducci A, Landoni F, Lissoni A, Maggino T, Zola P, et al. Clinical behavior of 203 stage II endometrial cancer cases: the impact of primary surgical approach and of adjuvant radiation therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001; 11:430–7.

Article18. Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Fowler J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:36–44.

Article19. Takayama S, Monma Y, Tsubota-Utsugi M, Nagase S, Tsubono Y, Numata T, et al. Food intake and the risk of endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma in Japanese women. Nutr Cancer. 2013; 65:954–60.

Article20. Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002; 11:1531–43.21. Dunn JE. Cancer epidemiology in populations of the United States–with emphasis on Hawaii and California–and Japan. Cancer Res. 1975; 35:3240–5.22. Ueda SM, Kapp DS, Cheung MK, Shin JY, Osann K, Husain A, et al. Trends in demographic and clinical characteristics in women diagnosed with corpus cancer and their potential impact on the increasing number of deaths. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198:218. e1–6.

Article23. Melamed A, Rauh-Hain JA, Clemmer JT, Diver EJ, Hall TR, Clark RM, et al. Changing trends in lymphadenectomy for endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126:815–22.

Article24. ASTEC study groupKitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009; 373:125–36.25. Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, Alberto Lissoni A, Signorelli M, Scambia G, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008; 100:1707–16.26. Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi M, Watari H, Takeda M, Sakuragi N. Survival effect of paraaortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010; 375:1165–72.

Article27. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (US). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Uterine neoplasms, version 2. 2016 [Internet]. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network;2016. [cited 2016 Oct 28]. Available from:. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf.28. Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, Bosse T, González-Martín A, Ledermann J, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Consensus Conference on Endometrial Cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016; 26:2–30.

Article29. Colombo N, Preti E, Landoni F, Carinelli S, Colombo A, Marini C, et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013; 24(Suppl 6):vi33–8.

Article30. Lee SW, Lee TS, Hong DG, No JH, Park DC, Bae JM, et al. Practice guidelines for management of uterine corpus cancer in Korea: a Korean Society of Gynecologic Oncology Consensus Statement. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017; 28:e12.

Article31. Nakano T. Status of Japanese radiation oncology. Radiat Med. 2004; 22:17–9.32. Teshima T, Owen JB, Hanks GE, Sato S, Tsunemoto H, Inoue T. A comparison of the structure of radiation oncology in the United States and Japan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996; 34:235–42.

Article33. Tanikawa T, Ohba H, Ogasawara K, Okuda Y, Ando Y. Geographical distribution of radiotherapy resources in Japan: investigating the inequitable distribution of human resources by using the Gini coefficient. J Radiat Res. 2012; 53:489–91.

Article34. Susumu N, Sagae S, Udagawa Y, Niwa K, Kuramoto H, Satoh S, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pelvic radiotherapy versus cisplatin-based combined chemotherapy in patients with intermediate- and high-risk endometrial cancer: a Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008; 108:226–33.

Article35. Maggi R, Lissoni A, Spina F, Melpignano M, Zola P, Favalli G, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy vs radiotherapy in high-risk endometrial carcinoma: results of a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2006; 95:266–71.

Article36. Johnson N, Bryant A, Miles T, Hogberg T, Cornes P. Adjuvant chemotherapy for endometrial cancer after hysterectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. CD003175.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The trend and outcome of postsurgical therapy for high-risk early-stage cervical cancer with lymph node metastasis in Japan: a report from the Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) guidelines evaluation committee

- Role of lymphadenectomy for ovarian cancer

- Opportunistic bilateral salpingectomy during benign gynecological surgery for ovarian cancer prevention: a survey of Gynecologic Oncology Committee of Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology 2018 guidelines for treatment of uterine body neoplasms

- Impact of institutional accreditation by the Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology on the treatment and survival of women with cervical cancer