Korean Circ J.

2018 Jun;48(6):481-491. 10.4070/kcj.2018.0088.

Understanding the Coronary Bifurcation Stenting

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hcgwon@naver.com

- KMID: 2412540

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2018.0088

Abstract

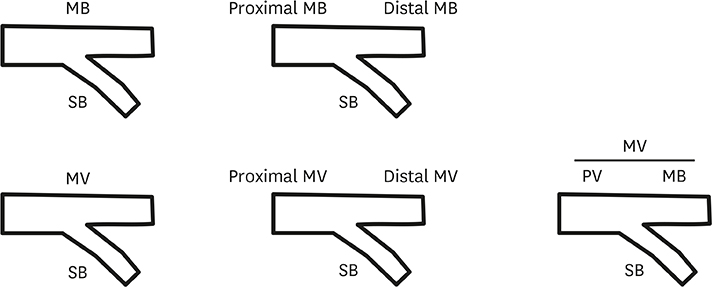

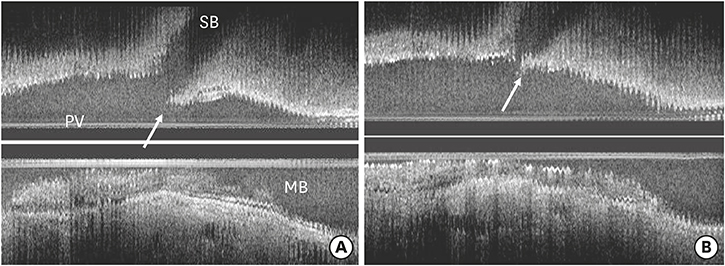

- Coronary bifurcation stenting is still complex and associated with a high risk of stent thrombosis and restenosis even with contemporary techniques. Although provisional approach has been proved to be the standard strategy of treatment, There is still lack of evidences for multiple steps of the procedure. For so many years we have been focused on the optimization of side branch (SB), but the clinical outcome is mostly dependent on the main vessel (MV) stenting. The optimal expansion of MV stent without the compromise of SB is the ultimate goal to achieve in the coronary bifurcation stenting. Understanding the anatomy and physiology of coronary bifurcation lesion should be the most important step to this goal. The relationship of vessel diameter between branches and the anatomical and functional significance of plaque shift and carina shift are two most important concepts to understand. They are the science behind the predictors of SB occlusion, and the rationale of proximal optimization technique and final kissing ballooning. This specific review will be devoted to review those concepts as well as clinical evidences to support them.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Serruys PW, Onuma Y, Garg S, et al. 5-year clinical outcomes of the ARTS II (Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study II. of the sirolimus-eluting stent in the treatment of patients with multivessel de novo coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:1093–1101.

Article2. Tanabe K, Hoye A, Lemos PA, et al. Restenosis rates following bifurcation stenting with sirolimus-eluting stents for de novo narrowings. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 94:115–118.

Article3. Ge L, Airoldi F, Iakovou I, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcome after implantation of drug-eluting stents in bifurcation lesions with the crush stent technique: importance of final kissing balloon post-dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:613–620.4. Nairooz R, Saad M, Elgendy IY, et al. Long-term outcomes of provisional stenting compared with a two-stent strategy for bifurcation lesions: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Heart. 2017; 103:1427–1434.5. Behan MW, Holm NR, Curzen NP, et al. Simple or complex stenting for bifurcation coronary lesions: a patient-level pooled-analysis of the Nordic Bifurcation Study and the British Bifurcation Coronary Study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011; 4:57–64.6. Colombo A, Jabbour RJ. Bifurcation lesions: no need to implant two stents when one is sufficient! Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:1929–1931.

Article7. Serruys PW. The treatment of coronary bifurcations: a true art form. EuroIntervention. 2015; 11:Suppl V. V7.

Article8. Lassen JF, Burzotta F, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for the left main stem and other bifurcation lesions: 12th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2018; 13:1540–1553.

Article9. Murray CD. The physiological principle of minimum work: I. The vascular system and the cost of blood volume. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1926; 12:207–214.

Article10. Hahn JY, Gwon HC, Kwon SU, et al. Comparison of vessel geometry in bifurcation between normal and diseased segments: intravascular ultrasound analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2008; 201:326–331.

Article11. Foin N, Secco GG, Ghilencea L, et al. Final proximal post-dilatation is necessary after kissing balloon in bifurcation stenting. EuroIntervention. 2011; 7:597–604.

Article12. Finet G, Gilard M, Perrenot B, et al. Fractal geometry of arterial coronary bifurcations: a quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound analysis. EuroIntervention. 2008; 3:490–498.

Article13. Kim JS, Hong MK, Ko YG, et al. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on long-term clinical outcomes in patients treated with drug-eluting stent for bifurcation lesions: data from a Korean multicenter bifurcation registry. Am Heart J. 2011; 161:180–187.

Article14. Nakamura S, Hall P, Maiello L, et al. Techniques for Palmaz-Schatz stent deployment in lesions with a large side branch. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995; 34:353–361.

Article15. Lefèvre T, Louvard Y, Morice MC, et al. Stenting of bifurcation lesions: classification, treatments, and results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000; 49:274–283.16. Medina A, Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M. A new classification of coronary bifurcation lesions. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006; 59:183.

Article17. Nakazawa G, Yazdani SK, Finn AV, et al. Pathological findings at bifurcation lesions: the impact of flow distribution on atherosclerosis and arterial healing after stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:1679–1687.18. Xu JQ, Song YB, Hahn JY, et al. Pattern of instent neointimal formation compared to native atherosclerosis in the coronary bifurcation lesions: volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013; 126:3505–3510.19. Vassilev D, Gil RJ. Relative dependence of diameters of branches in coronary bifurcations after stent implantation in main vessel--importance of carina position. Kardiol Pol. 2008; 66:371–378.20. Koo BK, Waseda K, Kang HJ, et al. Anatomic and functional evaluation of bifurcation lesions undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3:113–119.

Article21. Xu J, Hahn JY, Song YB, et al. Carina shift versus plaque shift for aggravation of side branch ostial stenosis in bifurcation lesions: volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis of both branches. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012; 5:657–662.22. Kang SJ, Kim WJ, Lee JY, et al. Hemodynamic impact of changes in bifurcation geometry after single-stent cross-over technique assessed by intravascular ultrasound and fractional flow reserve. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 82:1075–1082.

Article23. Koo BK, Kang HJ, Youn TJ, et al. Physiologic assessment of jailed side branch lesions using fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:633–637.

Article24. Hahn JY, Chun WJ, Kim JH, et al. Predictors and outcomes of side branch occlusion after main vessel stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the COBIS II Registry (COronary BIfurcation Stenting). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:1654–1659.25. Park JJ, Chun EJ, Cho YS, et al. Potential predictors of side-branch occlusion in bifurcation lesions after percutaneous coronary intervention: a coronary CT angiography study. Radiology. 2014; 271:711–720.

Article26. Darremont O, Leymarie JL, Lefèvre T, Albiero R, Mortier P, Louvard Y. Technical aspects of the provisional side branch stenting strategy. EuroIntervention. 2015; 11:Suppl V. V86–V90.

Article27. Mylotte D, Routledge H, Harb T, et al. Provisional side branch-stenting for coronary bifurcation lesions: evidence of improving procedural and clinical outcomes with contemporary techniques. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 82:E437–E445.28. Song PS, Song YB, Yang JH, et al. Periprocedural myocardial infarction is not associated with an increased risk of long-term cardiac mortality after coronary bifurcation stenting. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 167:1251–1256.

Article29. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007; 115:2344–2351.30. Poerner TC, Kralev S, Voelker W, et al. Natural history of small and medium-sized side branches after coronary stent implantation. Am Heart J. 2002; 143:627–635.

Article31. Pan M, Medina A, Romero M, et al. Assessment of side branch predilation before a provisional T-stent strategy for bifurcation lesions. A randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2014; 168:374–380.

Article32. Pan M, Suárez de Lezo J, Medina A, et al. Six-month intravascular ultrasound follow-up of coronary bifurcation lesions treated with rapamycin-eluting stents: technical considerations. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005; 58:1278–1286.

Article33. Niemelä M, Kervinen K, Erglis A, et al. Randomized comparison of final kissing balloon dilatation versus no final kissing balloon dilatation in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions treated with main vessel stenting: the Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study III. Circulation. 2011; 123:79–86.34. Kim YH, Lee JH, Roh JH, et al. Randomized comparisons between different stenting approaches for bifurcation coronary lesions with or without side branch stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015; 8:550–560.35. Song YB, Hahn JY, Song PS, et al. Randomized comparison of conservative versus aggressive strategy for provisional side branch intervention in coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the SMART-STRATEGY (Smart Angioplasty Research Team-Optimal Strategy for Side Branch Intervention in Coronary Bifurcation Lesions) randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012; 5:1133–1140.36. Koo BK, Park KW, Kang HJ, et al. Physiological evaluation of the provisional side-branch intervention strategy for bifurcation lesions using fractional flow reserve. Eur Heart J. 2008; 29:726–732.

Article37. Finet G, Derimay F, Motreff P, et al. Comparative analysis of sequential proximal optimizing technique versus kissing balloon inflation technique in provisional bifurcation stenting: fractal coronary bifurcation bench test. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015; 8:1308–1317.38. Steigen TK, Maeng M, Wiseth R, et al. Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation. 2006; 114:1955–1961.39. Colombo A, Moses JW, Morice MC, et al. Randomized study to evaluate sirolimus-eluting stents implanted at coronary bifurcation lesions. Circulation. 2004; 109:1244–1249.

Article40. Colombo A, Bramucci E, Saccà S, et al. Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side-branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: the CACTUS (Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stents) Study. Circulation. 2009; 119:71–78.41. Ferenc M, Gick M, Comberg T, et al. Culotte stenting vs. TAP stenting for treatment of de-novo coronary bifurcation lesions with the need for side-branch stenting: the Bifurcations Bad Krozingen (BBK) II angiographic trial. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:3399–3405.

Article42. Erglis A, Kumsars I, Niemelä M, et al. Randomized comparison of coronary bifurcation stenting with the crush versus the culotte technique using sirolimus eluting stents: the Nordic stent technique study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2:27–34.43. Chen SL, Xu B, Han YL, et al. Comparison of double kissing crush versus Culotte stenting for unprotected distal left main bifurcation lesions: results from a multicenter, randomized, prospective DKCRUSH-III study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:1482–1488.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- An Unusual Case of Guide Wire Fracture during Coronary Artery Stenting for Bifurcation Lesion

- Sex Differences in Procedural Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Bifurcation PCI

- Consecutive Jailed- and Kissing-Corsair Technique: Side Branch Protection and Dilation during Stent Implantation

- Predictors of side branch occlusions just after coronary stenting

- Long-term outcomes of simple crossover stenting from the left main to the left anterior descending coronary artery