J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2018 Mar;59(3):246-251. 10.3341/jkos.2018.59.3.246.

Change in Axial Length in Highly Myopic Adults Using Partial Coherence Interferometry

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Yangsan, Korea. jlee@pusan.ac.kr

- 2Medical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 3Department of Ophthalmology, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 4Research Institute for Convergence of Biomedical Science and Technology, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea.

- KMID: 2406959

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2018.59.3.246

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the change in axial length (AL) in highly myopic adults using partial coherence interferometry, and to identify the factors associated with the increase in AL.

METHODS

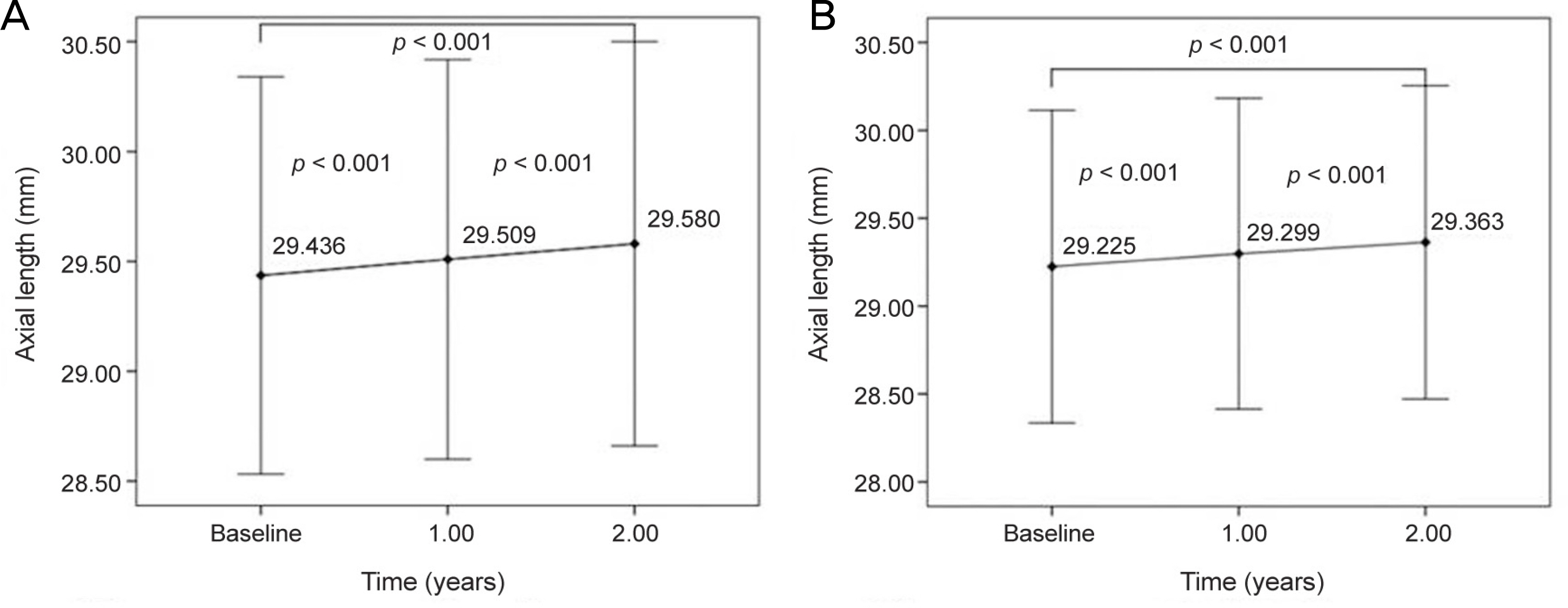

Medical records of highly myopic adults (≥−6 diopters [D] or AL ≥ 26.0 mm) were retrospectively reviewed. The AL of each patient was measured using partial coherence interferometry at least three times over 2 years, and the yearly change in AL was calculated. Associations between age, AL, choroidal thickness, and the rate of AL change were evaluated using multiple regression analysis.

RESULTS

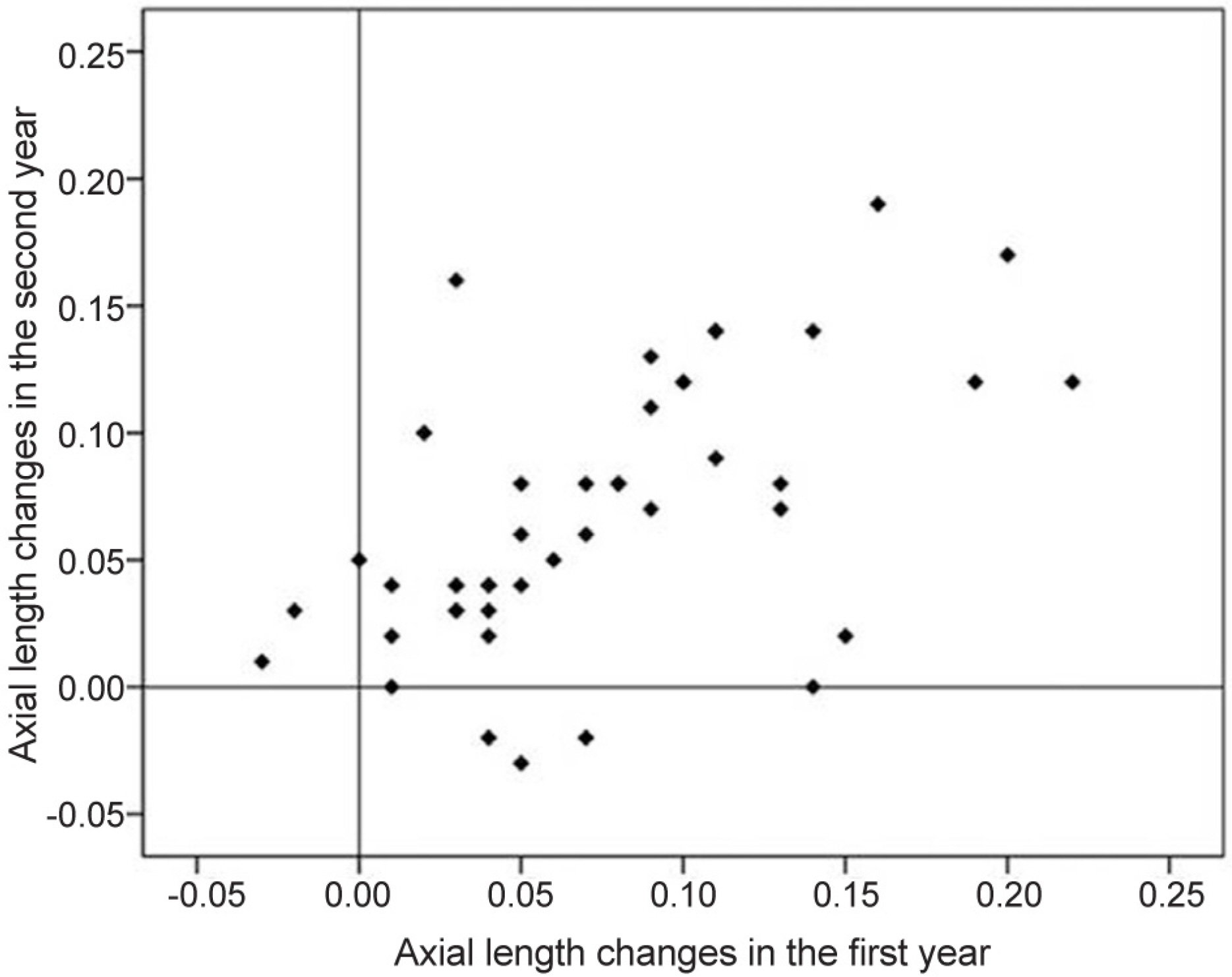

In total, 24 patients (4 males, 20 females) and 44 eyes were included in this study. The mean age was 54.9 ± 10.4 years, the initial AL was 29.335 ± 2.006 mm, the choroidal thickness was 72.7 ± 41.80 µm, the average spherical equivalent was −11.86 ± 3.85 D (−5.1~−22.0 D), and the mean follow-up period was 2.2 ± 0.5 years. A significant increase in AL of ≥0.05 mm was observed in 38 eyes (86.4%) at 2 years. The mean AL was significantly increased, to 29.409 ± 2.007 mm (p < 0.001), at 1 year and to 29.476 ± 2.028 mm (p < 0.001) at 2 years. The average rate of AL change was 0.071 ± 0.049 mm (−0.01~0.19 mm) per year. None of the included factors showed an association with the rate of AL change in multiple regression analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, an increase in AL in highly myopic adults was more frequent than in previous reports using A-scan. Periodic measurements are therefore recommended for the early detection of complications.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1). Saw SM, Katz J, Schein OD, et al. Epidemiology of myopia. Epidemiol Rev. 1996; 18:175–87.

Article2). Saw SM, Tong L, Chua WH, et al. Incidence and progression of myopia in Singaporean school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46:51–7.

Article3). Seet B, Wong TY, Tan DT, et al. Myopia in Singapore: taking a public health approach. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001; 85:521–6.

Article4). Wong TY, Foster PJ, Hee J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in adult Chinese in Singapore. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41:2486–94.5). He M, Zeng J, Liu Y, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern china. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45:793–9.

Article6). Sperduto RD, Seigel D, Roberts J, Rowland M. Prevalence of myopia in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983; 101:405–7.

Article7). Vitale S, Cotch MF, Sperduto RD. Prevalence of visual impairment in the United States. JAMA. 2006; 295:2158–63.

Article8). Wensor M, McCarty CA, Taylor HR. Prevalence and risk factors of myopia in Victoria, Australia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999; 117:658–63.

Article9). Lu P, Chen X, Zhang W, et al. Prevalence of ocular disease in Tibetan primary school children. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008; 43:95–9.

Article10). Naidoo KS, Raghunandan A, Mashige KP, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44:3764–70.

Article11). Kim DM. Refraction in young adults. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1983; 24:711–5.12). Kim JC. A statistical analysis of the ocular status of young adults in Seoul. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1985; 26:1055–61.13). Kang SH, Kim PS, Choi DG. Prevalence of myopia in 19-year-old Korean males: the relationship between the prevalence and education or urbanization. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2004; 45:2082–7.14). Lee SJ, Kim JM, Yu BC, et al. Prevalence of myopia in 19-year-old men in gyeongsangnam-do, Ulsan and Busan in 2002. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2009; 50:1392–403.

Article15). Saka N, Ohno-Matsui K, Shimada N, et al. Long-term changes in axial length in adult eyes with pathologic myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010; 150:562–8.e1.

Article16). Koh V, Yang A, Saw SM, et al. Differences in prevalence of refractive errors in young Asian males in Singapore between 1996-1997 and 2009-2010. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014; 21:247–55.

Article17). Risk factors for idiopathic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Am J Epidemiol. 1993; 137:749–57.18). Mitchell P, Hourihan F, Sandbach J, Wang JJ. The relationship between glaucoma and myopia: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:2010–5.19). Buch H, Vinding T, La Cour M, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness among 9980 Scandinavian adults: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:53–61.20). Javitt JC, Chiang YP. The socioeconomic aspects of laser refractive surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994; 112:1526–30.

Article21). Buch H, Vinding T, Nielsen NV. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment according to World Health Organization and United States criteria in an aged, urban Scandinavian population: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:2347–57.

Article22). Cedrone C, Nucci C, Scuderi G, et al. Prevalence of blindness and low vision in an Italian population: a comparison with other European studies. Eye (Lond). 2006; 20:661–7.

Article23). Klaver CC, Wolfs RC, Vingerling JR, et al. Age-specific prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in an older population: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998; 116:653–8.24). Shah M, Khan M, Khan MT, et al. Causes of visual impairment in children with low vision. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011; 21:88–92.25). Pi LH, Chen L, Liu Q, et al. Prevalence of eye diseases and causes of visual impairment in school-aged children in Western China. J Epidemiol. 2012; 22:37–44.

Article26). Sainz-Gomez C, Fernandez-Robredo P, Salinas-Alaman A, et al. Prevalence and causes of bilateral blindness and visual impairment among institutionalized elderly people in Pamplona, Spain. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010; 20:442–50.27). Khan SA. A retrospective study of low-vision cases in an Indian tertiary eye-care hospital. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2000; 48:201–7.28). Holladay JT. Refractive power calculations for intraocular lenses in the phakic eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993; 116:63–6.

Article29). Drexler W, Findl O, Menapace R, et al. Partial coherence interferometry: a novel approach to biometry in cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998; 126:524–34.

Article30). Verhulst E, Vrijghem JC. Accuracy of intraocular lens power calculations using the Zeiss IOL master. A prospective study. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2001; (281):61–5.31). Kimura S, Hasebe S, Miyata M, et al. Axial length measurement using partial coherence interferometry in myopic children: repeatability of the measurement and comparison with refractive components. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2007; 51:105–10.

Article32). Connors R, Boseman P, Olson RJ. Accuracy and reproducibility of biometry using partial coherence interferometry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002; 28:235–8.

Article33). Rajan MS, Keilhorn I, Bell JA. Partial coherence laser interferometry vs conventional ultrasound biometry in intraocular lens power calculations. Eye (Lond). 2002; 16:552–6.

Article34). Song BY, Yang KJ, Yoon KC. Accuracy of partial coherence interferometry in intraocular lens power calculation. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2005; 46:775–80.35). Oslen T, Thorwest M. Calibration of axial length measurements with the Zeiss IOLMaster. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005; 31:1345–50.36). Ohsugi H, Ikuno Y, Shoujou T, et al. Axial length changes in highly myopic eyes and influence of myopic macular complications in Japanese adults. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0180851.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Accuracy of Partial Coherence Interferometry in Intraocular Lens Power Calculation

- The Accuracy of Axial Length Measurement Using Partial Coherence Interferometrys

- Comparison of Formulas for Intraocular Lens Power Calculation Installed in a Partial Coherence Interferometer

- Comparison of Partial Interferometry and Ultrasound A-scan for Axial Length Measurement in Retinal Vein Occlusions

- Biometry with Partial Coherence Interferometry and Ultrasonography in High Myopes