J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2018 Mar;59(3):217-222. 10.3341/jkos.2018.59.3.217.

Effectiveness of Mitomycin C Combined with Amniotic Membrane Transplantation to Treat Recurrent Pterygia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea. kopupil@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2406955

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2018.59.3.217

Abstract

- PURPOSE

We evaluated a combination of intraoperative mitomycin C (MMC) and amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) for treating recurrent pterygia.

METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed 40 eyes of 39 patients with recurrent pterygia who underwent AMT from December 2007 to July 2015 and who were followed-up for a minimum of 12 months. In all, 22 eyes received intraoperative MMC (group A) and 18 did not (group B). Recurrence rates and complications were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

Conjunctival recurrence was noted in two and corneal recurrence was noted in four eyes of group A (27.3%); the figures for group B were four and three (38.9%). These recurrence rates were not significantly different (p = 0.545). In five cases with preoperative symblepharon, this condition recurred when MMC was not used (two eyes) but not when MMC was used (three eyes). No major complications such as necrotizing scleritis, scleromalacia, or corneal ulcer were observed in either group after surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Intraoperative adjunct MMC therapy did not significantly inhibit recurrence after AMT for treating recurrent pterygia but may reduce the recurrence rate of symblepharon.

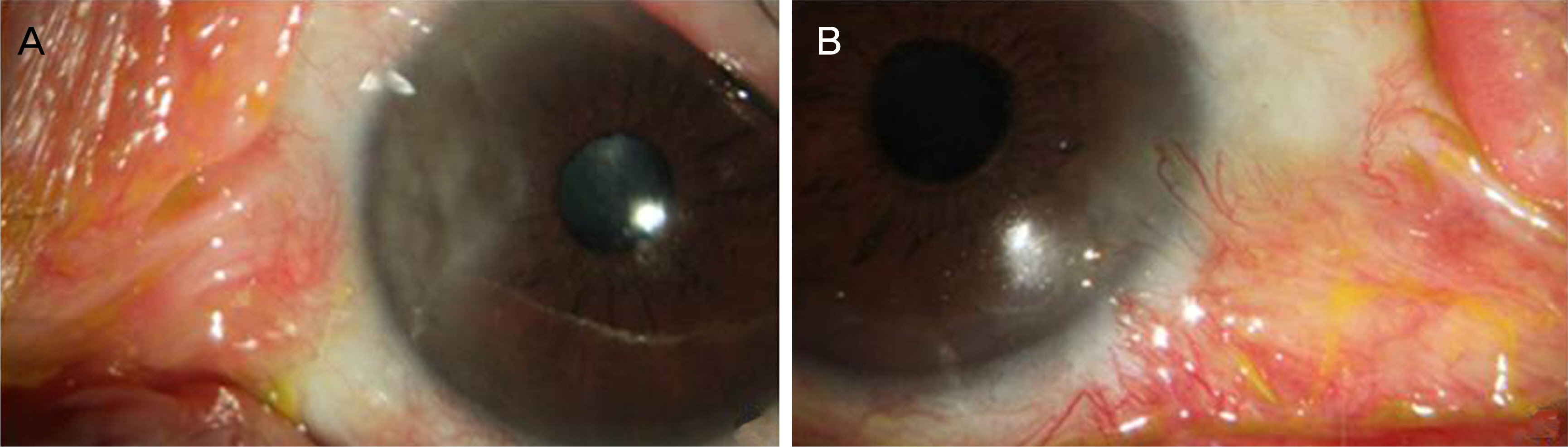

Figure

Reference

-

1). Dushku N, John MK, Schultz GS, Reid TW. Pterygia pathogenesis: corneal invasion by matrix metalloproteinase expressing altered limbal epithelial basal cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119:695–706.2). Pinkerton OD, Hokama Y, Shigemura LA. Immunologic basis for the pathogenesis of pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984; 98:225–8.

Article3). Lee SH, Jeong HJ. Immune reactions in pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1987; 28:927–33.4). Detorakis ET, Spandidos DA. Pathogenetic mechanisms and treatment options for ophthalmic pterygium: trends and perspectives (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2009; 23:439–47.

Article5). Baharassa F, Datta R. Postoperative beta radiation treatment of pterygium. Int J Radiat Oncolo Biol Phys. 1983; 9:679–84.6). Kunitomo N, Mori S. Studies on the pterygium. Report IV! A treatment of the pterygium by mitomycin C instillation. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1963; 67:601–7.7). Hayasaka S, Noda S, Yamamoto Y, Setogawa T. Postoperative instillation of low dose mitomycin C in the treatment of primary pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988; 106:715–8.8). Frucht-Pery J, Siganos CS, Ilsar M. Intraoperative application of topical mitomycin C for pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103:674–7.

Article9). Hirst LW. The treatment of pterygium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003; 48:145–80.

Article10). Min JB, Choi YS, Kim JY. Immunohistochemical study of PCNA(Proliferating cell nuclear antigen) in pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1999; 40:70–4.11). Lam DS, Wong AK, Fan DS, et al. Intraoperative mitomycin C to prevent recurrence of pterygium after excision: a 30-month follow-up study. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105:901–4. discussion 904-5.12). Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SC. Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary closure for pterygium excision. Ophthalmology. 1997; 104:974–85.

Article13). Shimazaki J, Kosaka K, Shimmura S, Tsubota K. Amniotic membrane transplantation with conjunctival autograft for recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2003; 110:119–24.

Article14). Lee BH, Lee JW, Park YJ, Lee KW. Clinical research on effectiveness of mitomycin C on primary pterygium with limbal-conjunctival autograft. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2009; 50:996–1004.

Article15). Bae SG, Kim JK, Lee JK, Park DJ. The effective of mitomycin C on pterygium surgery with amniotic membrane transplantation. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2012; 53:200–7.16). Tan DT, Chee SP, Dear KB, Lim AS. Effect of pterygium morphology on pterygium recurrence in a controlled trial comparing conjunctival autografting with bare sclera excision. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997; 115:1235–40.

Article17). Solomon A, Espana EM, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for reconstruction of the conjunctival fornices. Ophthalmology. 2003; 110:93–100.

Article18). Bradley JC, Yang W, Bradley RH, et al. The science of pterygia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010; 94:815–20.

Article19). Ehrlich D. The management of pterygium. Ophthalmic Surg. 1977; 8:23–30.

Article20). Mutlu FM, Sobaci G, Tatar T, Yildirim E. A comparative study of recurrent pterygium surgery: limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation versus mitomycin C with conjunctival flap. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:817–21.

Article21). Frucht-Pery J, Raiskup F, Ilsar M, et al. Conjunctival autografting combined with low-dose mitomycin C for preventing of primary pterygium recurrence. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006; 141:1044–50.22). Sonnenberg A, Calafat J, Janssen H, et al. Integrin alpha 6/beta 4 complex is located in hemidesmosomes, suggesting a major role in epidermal cell-basement membrane adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1991; 113:907–17.

Article23). Streuli CH, Bailey N, Bissel MJ. Control of mammary epithelial differentiation: basement membrane induces tissue-specific gene expression in the absence of cell-cell interaction and morphological polarity. J Cell Biol. 1991; 115:1383–95.

Article24). Na BK, Hwang JH, Kim JC, et al. Analysis of human amniotic membrane components as proteinase inhibitors for development of therapeutic agent for recalcitrant keratitis. Placenta. 1999; 20:453–66.

Article25). Kim KW, Kim JC. The clinical effect of micro-multiporous expanded polytetrafluoroethylene insertion for recurrent pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013; 54:416–26.

Article26). Ozgurhan EB, Agca A, Kara N, et al. Topical application of bevacizumab as an adjunct to recurrent pterygium surgery. Cornea. 2013; 32:835–8.

Article27). Verweij J, Pinedo HM. Mitomycin C: mechanism of action, usefulness and limitations. Anticancer Drugs. 1990; 1:5–13.28). Rubinfeld RS, Pfister RR, Stein RM, et al. Serious complications of topical mitomycin-C after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992; 99:1647–54.

Article29). Solomon A, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation after extensive removal of primary and recurrent pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:449–60.

Article30). Keklikci U, Celik Y, Cakmak SS, et al. Conjunctival-limbal autograft, amniotic membrane transplantation, and intraoperative mitomycin C for primary pterygium. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie). 2007; Winter. 39:296–301.

Article31). Wong VA, Law FC. Use of mitomycin C with conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery in Asian-Canadians. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:1512–5.

Article32). Ma DH, See LC, Hwang YS, Wang SF. Comparison of amniotic membrane graft alone or combined with intraoperative mitomycin C to prevent recurrence after excision of recurrent pterygia. Cornea. 2005; 24:141–50.

Article33). Salman AG, Mansour DE. The recurrence of pterygium after different modalities of surgical treatment. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmol. 2011; 25:411–5.

Article34). Yao YF, Qiu WY, Zhang YM, Tseng SC. Mitomycin C, amniotic membrane transplantation and limbal conjunctival autograft for treating multirecurrent pterygia with symblepharon and motility restriction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006; 244:232–6.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Amniotic Membrane Transplantation and Use of Adjunctive Mitomycin C in the Treatment of Symblepharon

- The Effectiveness of Mitomycin C on Pterygium Surgery with Amniotic Membrane Transplantation

- Ocular Surface Reconstruction with Amniotic Membrane Transplantation in Pterygium

- Treatment of Pterygium with Amniotic Membrane Transplantation

- The Effect of Amniotic Membrane Transplantation for Pterygium Excision