Intest Res.

2018 Jan;16(1):134-141. 10.5217/ir.2018.16.1.134.

Clinical outcomes of surveillance colonoscopy for patients with sessile serrated adenoma

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea. bodnsoul@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2402657

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2018.16.1.134

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/AIMS

Sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs) are known to be precursors of colorectal cancer (CRC). The proper interval of follow-up colonoscopy for SSAs is still being debated. We sought to determine the proper interval of colonoscopy surveillance in patients diagnosed with SSAs in South Korea.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients diagnosed with SSAs who received 1 or more follow-up colonoscopies. The information reviewed included patient baseline characteristics, SSA characteristics, and colonoscopy information.

RESULTS

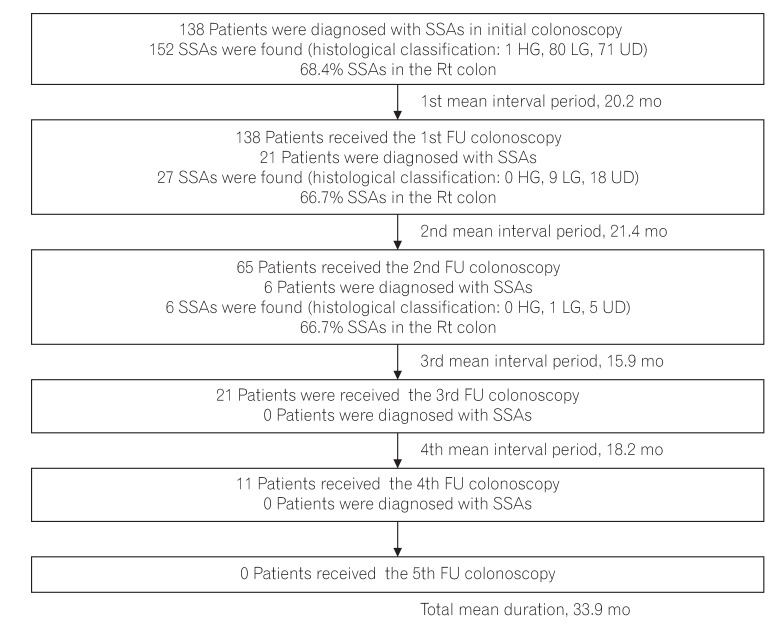

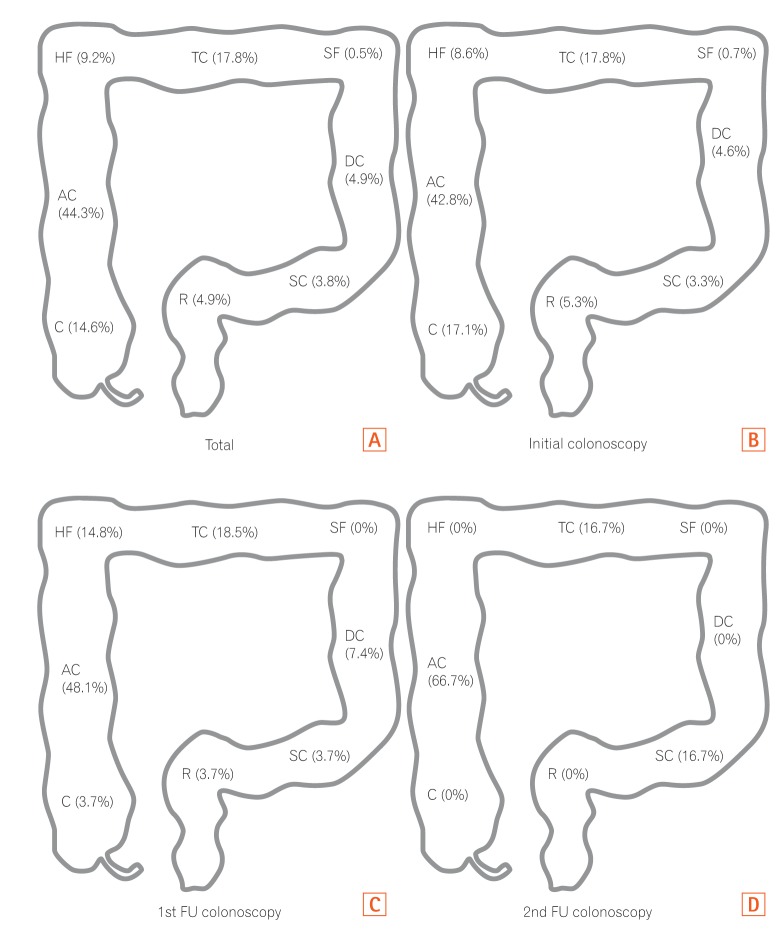

From January 2007 to December 2011, 152 SSAs and 8 synchronous adenocarcinomas were identified in 138 patients. The mean age of the patients was 62.2 years and 60.1% patients were men. SSAs were located in the right colon (i.e., from the cecum to the hepatic flexure) in 68.4% patients. At the first follow-up, 27 SSAs were identified in 138 patients (right colon, 66.7%). At the second follow-up, 6 SSAs were identified in 65 patients (right colon, 66.7%). At the 3rd and 4th follow-up, 21 and 11 patients underwent colonoscopy, respectively, and no SSAs were detected. The total mean follow-up duration was 33.9 months. The mean size of SSAs was 8.1±5.0 mm. SSAs were most commonly found in the right colon (126/185, 68.1%). During annual follow-up colonoscopy surveillance, no cancer was detected.

CONCLUSIONS

Annual colonoscopy surveillance is not necessary for identifying new CRCs in all patients diagnosed with SSAs. In addition, the right colon should be examined more carefully because SSAs occur more frequently in the right colon during initial and follow-up colonoscopies.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Surveillance colonoscopy in patients with sessile serrated adenoma

Ji Hyung Nam, Hyoun Woo Kang

Intest Res. 2018;16(3):502-503. doi: 10.5217/ir.2018.16.3.502.

Reference

-

1. Rosty C, Hewett DG, Brown IS, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Gastroenterol. 2013; 48:287–302. PMID: 23208018.2. Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1315–1329. PMID: 22710576.

Article3. Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011; 42:1–10. PMID: 20869746.4. Noffsinger AE. Serrated polyps and colorectal cancer: new pathway to malignancy. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009; 4:343–364. PMID: 19400693.

Article5. Bauer VP, Papaconstantinou HT. Management of serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008; 21:273–279. PMID: 20011438.6. Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2088–2100. PMID: 20420948.7. Huang CS, Farraye FA, Yang S, O'Brien MJ. The clinical significance of serrated polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106:229–240. PMID: 21045813.8. Aust DE, Baretton GB. Members of the Working Group GI-Pathology of the German Society of Pathology. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps)-proposal for diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch. 2010; 457:291–297. PMID: 20617338.9. Sweetser S, Smyrk TC, Sugumar A. Serrated polyps: critical precursors to colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 5:627–635. PMID: 21910580.10. Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1106–1114. PMID: 24047060.11. le Clercq CM, Bouwens MW, Rondagh EJ, et al. Postcolonoscopy colorectal cancers are preventable: a population-based study. Gut. 2014; 63:957–963. PMID: 23744612.

Article12. Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:1977–1981. PMID: 8247072.

Article13. Lieberman DA. American Gastroenterological Association. Colon polyp surveillance: clinical decision tool. Gastroenterology. 2014; 146:305–306. PMID: 24269291.

Article14. Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau JM, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2013; 45:842–851. PMID: 24030244.

Article15. Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012; 143:844–857. PMID: 22763141.

Article16. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorec-tal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut. 2010; 59:666–689. PMID: 20427401.

Article17. British Columbia Medical Association. BCGuidelines.ca: follow-up of colorectal polyps or cancer. Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Health;2013.18. Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for surveillance colonoscopy: in adenoma follow-up; following curative resection of colorectal cancer; and for cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Accessed July 4, 2017. http://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Colorectal_cancer/Colonoscopy_surveillance .19. Baron TH, Smyrk TC, Rex DK. Recommended intervals between screening and surveillance colonoscopies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013; 88:854–858. PMID: 23910411.

Article20. Buda A, De Bona M, Dotti I, et al. Prevalence of different subtypes of serrated polyps and risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk population undergoing first-time colonoscopy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012; 3:e6. DOI: 10.1038/ctg.2011.5. PMID: 23238028.

Article21. IJspeert JE, de Wit K, van der Vlugt M, Bastiaansen BA, Fockens P, Dekker E. Prevalence, distribution and risk of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps at a center with a high adenoma detection rate and experienced pathologists. Endoscopy. 2016; 48:740–746. PMID: 27110696.

Article22. Li D, Jin C, McCulloch C, et al. Association of large serrated polyps with synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:695–702. PMID: 19223889.

Article23. Schreiner MA, Weiss DG, Lieberman DA. Proximal and large hyperplastic and nondysplastic serrated polyps detected by colonoscopy are associated with neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2010; 139:1497–1502. PMID: 20633561.

Article24. Hiraoka S, Kato J, Fujiki S, et al. The presence of large serrated polyps increases risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 139:1503–1510. PMID: 20643134.

Article25. Lu FI, van Niekerk de W, Owen D, Tha SP, Turbin DA, Webber DL. Longitudinal outcome study of sessile serrated adenomas of the colorectum: an increased risk for subsequent right-sided colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:927–934. PMID: 20551824.

Article26. Vu HT, Lopez R, Bennett A, Burke CA. Individuals with sessile serrated polyps express an aggressive colorectal phenotype. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011; 54:1216–1223. PMID: 21904135.

Article27. Glazer E, Golla V, Forman R, Zhu H, Levi G, Bodenheimer HC Jr. Serrated adenoma is a risk factor for subsequent adenomatous polyps. Dig Dis Sci. 2008; 53:2204–2207. PMID: 18320324.

Article28. Álvarez C, Andreu M, Castells A, et al. Relationship of colonoscopy-detected serrated polyps with synchronous advanced neoplasia in average-risk individuals. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013; 78:333–341.e1. PMID: 23623039.

Article29. Zhu H, Zhang G, Yi X, et al. Histology subtypes and polyp size are associated with synchronous colorectal carcinoma of colorectal serrated polyps: a study of 499 serrated polyps. Am J Cancer Res. 2014; 5:363–374. PMID: 25628945.30. Leung WK, Tang V, Lui PC. Detection rates of proximal or large serrated polyps in Chinese patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. J Dig Dis. 2012; 13:466–471. PMID: 22908972.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Strategy for post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: focus on the revised Korean guidelines

- Korean Guidelines for Postpolypectomy Colonoscopic Surveillance: 2022 Revision

- Surveillance colonoscopy in patients with sessile serrated adenoma

- Characteristics and outcomes of endoscopically resected colorectal cancers that arose from sessile serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas

- Serrated Polyposis Syndrome with a Synchronous Colon Adenocarcinoma Treated by an Endoscopic Mucosal Resection