Korean J Orthod.

2009 Oct;39(5):330-337.

What determines dental protrusion or crowding while both malocclusions are caused by large tooth size?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, Chonnam National University, Korea.

- 2Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Korea.

- 3Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Korea.

- 4Korean Adult Occlusion Study Center, Korea.

- 5Department of Orthodontics, 2nd Stage of Brain Korea 21, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Korea. hhwang@chonnam.ac.kr

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the differences in lateral cephalometric characteristics between patients with dental protrusion and crowding in order to determine what factors affect dental protrusion or crowding while both malocclusion types are caused by large tooth size.

METHODS

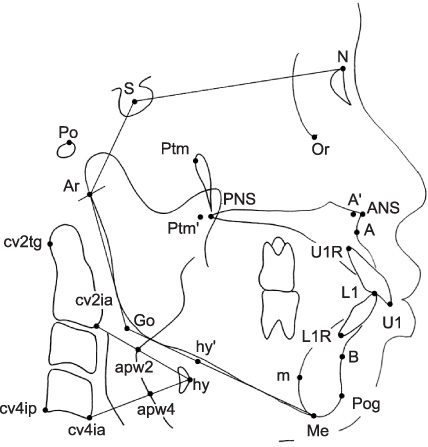

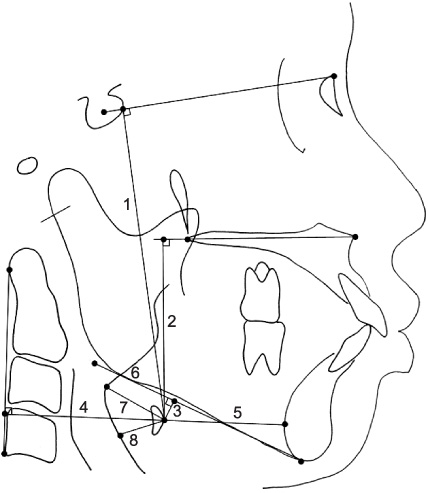

Twenty nine individuals with dental protrusion and 22 individuals with dental crowding were enrolled in this study. All subjects had larger teeth than average and Class I molar relationships. Craniofacial characteristics and hyoid bone positions were determined from lateral cephalograms and compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

In the comparisons of craniofacial characteristics, the measurements indicating maxillary length and facial convexity showed greater values in the protrusion group than in the crowding group. Comparisons of hyoid bone positions showed that the hyoid bone was positioned more anteriorly and superiorly in the protrusion group than in the crowding group.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study indicate that some craniofacial characteristics and tongue position may affect the development of dental protrusion or crowding; when an individual has large teeth, dental protrusion or crowding might be determined according to maxillary growth and tongue position.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Downs WB. Analysis of the dentofacial profile. Angle Orthod. 1956. 26:191–212.2. Graber TM. Orthodontics: principles and practice. 1972. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders;437–447.3. Posen AL. The influence of maximum perioral and tongue force on the incisor teeth. Angle Orthod. 1972. 42:285–309.4. Cox NH, van der Linden FP. Facial harmony. Am J Orthod. 1971. 60:175–183.

Article5. Keating PJ. Bimaxillary protrusion in the Caucasian: a cephalometric study of the morphological features. Br J Orthod. 1985. 12:193–201.

Article6. McCann J, Burden DJ. An investigation of tooth size in Northern Irish people with bimaxillary dental protrusion. Eur J Orthod. 1996. 18:617–621.

Article7. Fastlicht J. Crowding of mandibular incisors. Am J Orthod. 1970. 58:156–163.

Article8. Norderval K, Wisth PJ, Böe OE. Mandibular anterior crowding in relation to tooth size and craniofacial morphology. Scand J Dent Res. 1975. 83:267–273.

Article9. Doris JM, Bernard BW, Kuftinec MM, Stom D. A biometric study of tooth size and dental crowding. Am J Orthod. 1981. 79:326–336.

Article10. Hwang HS, Kim JT, Cho JH, Baik HS. Relationship of dental crowding to tooth size and arch width. Korean J Orthod. 2004. 34:488–496.11. Fonseca RJ, Klein WD. A cephalometric evaluation of American Negro women. Am J Orthod. 1978. 73:152–160.

Article12. Mitchell JI, Williamson EH. A comparison of maximum perioral muscle forces in North American blacks and whites. Angle Orthod. 1978. 48:126–131.13. Posen AL. The application of quantitative perioral assessment to orthodontic case analysis and treatment planning. Angle Orthod. 1976. 46:118–143.14. Lamberton CM, Reichart PA, Triratananimit P. Bimaxillary protrusion as a pathologic problem in the Thai. Am J Orthod. 1980. 77:320–329.

Article15. Kim DS, Kim YJ, Choi JH, Han JH. A study of Korean norm about tooth size and ratio in Korean adults with normal occlusion. Korean J Orthod. 2001. 31:505–515.16. Garn SM. McNamara JA, editor. Genetics of dental development. The biology of occlusal development. Craniofacial Growth Series. 1977. Vol 7. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for Human Growth and Development, The University of Michigan;61–88.17. Moyers RE. Moyers RE, editor. Analysis of the dentition and occlusion. Handbook of orthodontics. 1988. Chicago, Il: Year Book Medical Publishers;221–246.18. Rose JC, Roblee RD. Origins of dental crowding and malocclusions: an anthropological perspective. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009. 30:292–300.19. Fromm B, Lundberg M. Postural behaviour of the hyoid bone in normal occlusion and before and after surgical correction of mandibular protrusion. Swed J Dent. 1970. 63:425–433.20. Bibby RE, Preston CB. The hyoid triangle. Am J Orthod. 1981. 80:92–97.

Article21. Gustavsson U, Hansson G, Holmqvist A, Lundberg M. Hyoid bone position in relation to head posture. Sven Tandlak Tidskr. 1972. 65:423–430.22. King EW. A roentgenographic study of pharyngeal growth. Angle Orthod. 1952. 22:23–37.23. Graber LW. Hyoid changes following orthopedic treatment of mandibular prognathism. Angle Orthod. 1978. 48:33–38.24. Tallgren A, Solow B. Long-term changes in hyoid bone position and craniocervical posture in complete denture wearers. Acta Odontol Scand. 1984. 42:257–267.

Article25. Carlsoo S, Leijon G. A radiographic study of the position of the hyo-laryngeal complex in relation to the skull and the cervical column in man. Trans R Sch Dent Stockh Umea. 1960. 5:13–34.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A statistical study of dental crowding and its relationship to tooth size, and arch dimension and shape

- A statistical study on the effect of tooth size and dental arch size upon the crowding

- Relationship of dental crowding to tooth size and arch width

- A comparative study on crowding according to the status of the third molars in mandibular arch

- A study on the relationship between tooth size and arch dimension in dental crowding