J Korean Med Sci.

2017 Oct;32(10):1603-1609. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.10.1603.

Incidence, Predictors, and Clinical Outcomes of New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Drug-Eluting Stent

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. mkhong61@yuhs.ac

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Yongin Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Yongin, Korea.

- 3Cardiovascular Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Severance Biomedical Science Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2400431

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.10.1603

Abstract

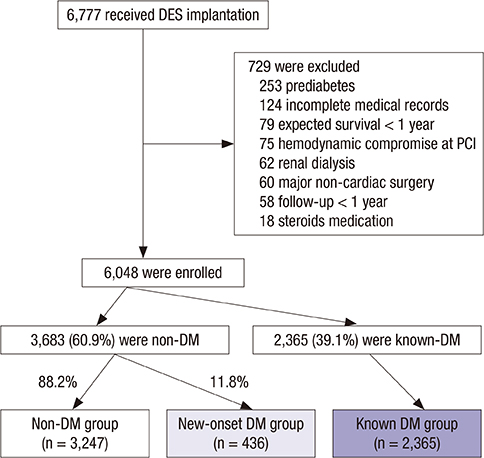

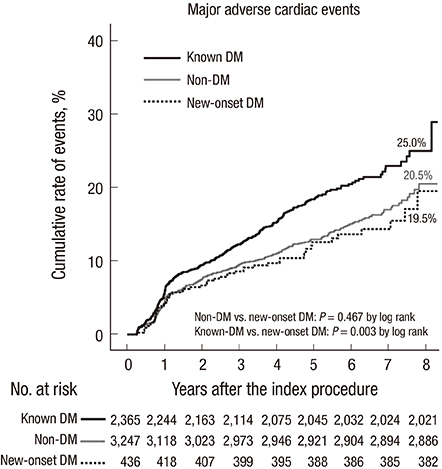

- We investigated the incidence, predictors, and long-term clinical outcomes of new-onset diabetes mellitus (DM) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent (DES). A total of 6,048 patients treated with DES were retrospectively reviewed and divided into three groups: 1) known DM (n = 2,365; fasting glucose > 126 mg/dL, glycated hemoglobin > 6.5%, already receiving DM treatment, or previous history of DM at the time of PCI); 2) non-DM (n = 3,247; no history of DM, no laboratory findings suggestive of DM at PCI, and no occurrence of DM during follow-up); and 3) new-onset DM (n = 436; non-DM features at PCI and occurrence of DM during follow-up). Among 3,683 non-DM patients, 436 (11.8%) patients were diagnosed with new-onset DM at 3.4 ± 1.9 years after PCI. Independent predictors for new-onset DM were high-intensity statin therapy, high body mass index (BMI), and high level of fasting glucose and triglycerides. The 8-year cumulative rate of major adverse cardiac events (a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, or any revascularization) in the new-onset DM group was 19.5%, which was similar to 20.5% in the non-DM group (P = 0.467), but lower than 25.0% in the known DM group (P = 0.003). In conclusion, the incidence of new-onset DM after PCI with DES was not low. High-intensity statin therapy, high BMI, and high level of fasting glucose and triglycerides were independent predictors for new-onset DM. Long-term clinical outcomes of patients with new-onset DM after PCI were similar to those of patients without DM.

MeSH Terms

-

Body Mass Index

Coronary Artery Disease

Diabetes Mellitus*

Drug-Eluting Stents*

Fasting

Glucose

Hemoglobin A, Glycosylated

Humans

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors

Incidence*

Myocardial Infarction

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention*

Retrospective Studies

Stents

Thrombosis

Triglycerides

Glucose

Triglycerides

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Statin and the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus

Sang-Hyun Kim

J Korean Med Assoc. 2017;60(11):901-911. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2017.60.11.901.Should We Intensify Statin Management in ACS Patients with Very Low LDL Cholesterol Levels?

Ki Hoon Han

J Lipid Atheroscler. 2019;8(2):204-207. doi: 10.12997/jla.2019.8.2.204.

Reference

-

1. Hammoud T, Tanguay JF, Bourassa MG. Management of coronary artery disease: therapeutic options in patients with diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 36:355–365.2. Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, Mitch W, Smith SC Jr, Sowers JR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999; 100:1134–1146.3. Folsom AR, Szklo M, Stevens J, Liao F, Smith R, Eckfeldt JH. A prospective study of coronary heart disease in relation to fasting insulin, glucose, and diabetes. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Diabetes Care. 1997; 20:935–942.4. Becker A, Bos G, de Vegt F, Kostense PJ, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CD. Cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes: comparison with nondiabetic individuals without and with prior cardiovascular disease. 10-year follow-up of the Hoorn Study. Eur Heart J. 2003; 24:1406–1413.5. Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Rinaldi MJ, Neumann FJ, Metzger DC, Henry TD, Cox DA, Duffy PL, Mazzaferri E, et al. Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES): a prospective multicentre registry study. Lancet. 2013; 382:614–623.6. Barsness GW, Peterson ED, Ohman EM, Nelson CL, DeLong ER, Reves JG, Smith PK, Anderson RD, Jones RH, Mark DB, et al. Relationship between diabetes mellitus and long-term survival after coronary bypass and angioplasty. Circulation. 1997; 96:2551–2556.7. Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002; 105:2696–2698.8. Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, Seshasai SR, McMurray JJ, Freeman DJ, Jukema JW, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010; 375:735–742.9. Kim S, Yun KH, Kang WC, Shin DH, Kim JS, Kim BK, Ko YG, Choi D, Jang Y, Hong MK. Comparison of full lesion coverage versus spot drug-eluting stent implantation for coronary artery stenoses. Yonsei Med J. 2014; 55:584–591.10. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 129:S1–45.11. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011; 34:Suppl 1. S11–S61.12. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007; 115:2344–2351.13. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Katus HA, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Clemmensen PM, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012; 126:2020–2035.14. LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, Shear C, Barter P, Fruchart JC, Gotto AM, Greten H, Kastelein JJ, Shepherd J, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1425–1435.15. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A 3rd, Goldstein LB, Hennerici M, Rudolph AE, Sillesen H, Simunovic L, Szarek M, Welch KM, et al. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:549–559.16. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM Jr, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2195–2207.17. Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Langendorfer A, Stein EA, Kruyer W, Gotto AM Jr. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA. 1998; 279:1615–1622.18. Waters DD, Ho JE, DeMicco DA, Breazna A, Arsenault BJ, Wun CC, Kastelein JJ, Colhoun H, Barter P. Predictors of new-onset diabetes in patients treated with atorvastatin: results from 3 large randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:1535–1545.19. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005; 112:2735–2752.20. Nesto RW. Correlation between cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus: current concepts. Am J Med. 2004; 116:Suppl 5A. 11S–22S.21. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC Jr, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009; 120:1640–1645.22. Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P, Peto R; Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003; 361:2005–2016.23. Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, DeMicco DA, Barter P, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011; 305:2556–2564.24. Xia F, Xie L, Mihic A, Gao X, Chen Y, Gaisano HY, Tsushima RG. Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis impairs insulin secretion and voltage-gated calcium channel function in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2008; 149:5136–5145.25. Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, Libby P, Glynn RJ. Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: an analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2012; 380:565–571.