Intest Res.

2017 Oct;15(4):524-528. 10.5217/ir.2017.15.4.524.

Fatal infections in older patients with inflammatory bowel disease on anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Paediatrics, University of Malaya Faculty of Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. leews@ummc.edu.my

- 2University Malaya Paediatrics and Child Health Research Group, University of Malaya Faculty of Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- 3Department of Medicine, University of Malaya Faculty of Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- 4Department of Medicine, University Sains Islam Malaysia Faculty of Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- KMID: 2396403

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2017.15.4.524

Abstract

- Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) is highly effective in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); however, it is associated with an increased risk of infections, particularly in older adults. We reviewed 349 patients with IBD, who were observed over a 12-month period, 74 of whom had received anti-TNF therapy (71 patients were aged <60 years and 3 were aged ≥60 years). All the 3 older patients developed serious infectious complications after receiving anti-TNFs, although all of them were also on concomitant immunosuppressive therapy. One patient developed disseminated tuberculosis, another patient developed cholera diarrhea followed by nosocomial pneumonia, while the third patient developed multiple opportunistic infections (Pneumocystis pneumonia, cryptococcal septicemia and meningitis, Klebsiella septicemia). All 3 patients died within 1 year from the onset of the infection(s). We recommend that anti-TNF, especially when combined with other immunosuppressive therapy, should be used with extreme caution in older adult patients with IBD.

MeSH Terms

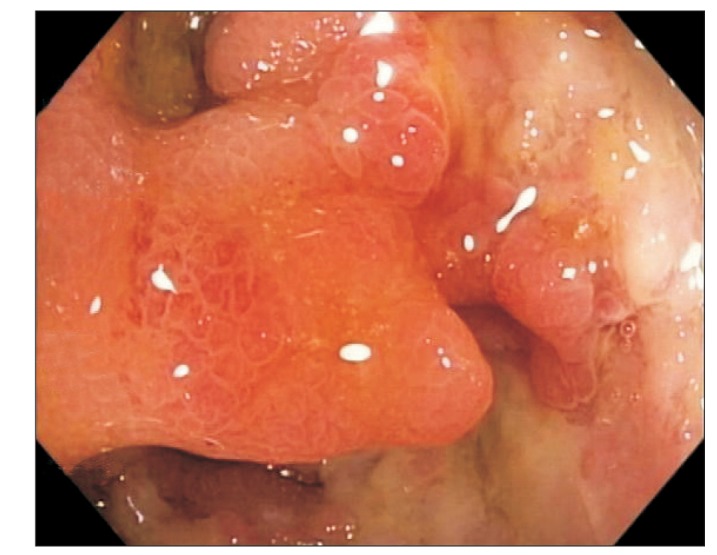

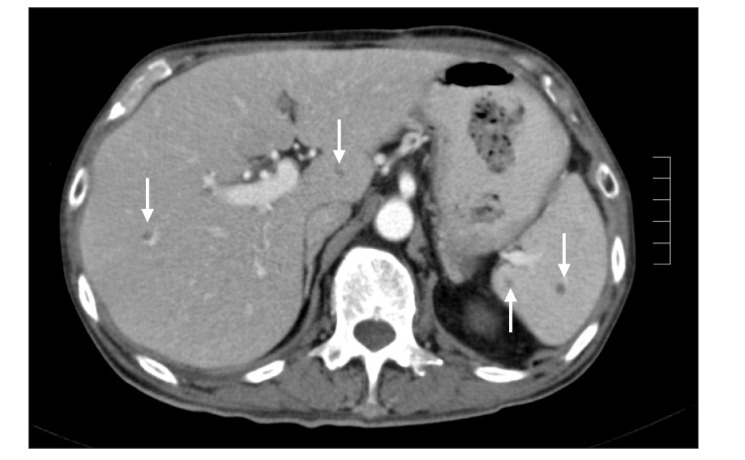

Figure

Reference

-

1. Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010; 4:28–62. PMID: 21122489.

Article2. Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012; 6:991–1030. PMID: 23040451.

Article3. Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002; 359:1541–1549. PMID: 12047962.

Article4. Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007; 56:1232–1239. PMID: 17299059.

Article5. Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance IC, et al. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:239–250. PMID: 17634459.

Article6. D’Haens GR, Panaccione R, Higgins PD, et al. The London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology on Biological Therapy for IBD with the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization: when to start, when to stop, which drug to choose, and how to predict response. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106:199–212. PMID: 21045814.

Article7. Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011; 60:571–607. PMID: 21464096.

Article8. Ueno F, Matsui T, Matsumoto T, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for Crohn’s disease, integrated with formal consensus of experts in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2013; 48:31–72. PMID: 23090001.

Article9. Park JJ, Yang SK, Ye BD, et al. Second Korean guidelines for the management of Crohn’s disease. Intest Res. 2017; 15:38–67. PMID: 28239314.

Article10. Choi CH, Moon W, Kim YS, et al. Second Korean guidelines for the management of ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2017; 15:7–37. PMID: 28239313.

Article11. Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, et al. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:1179–1207. PMID: 24909831.12. Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Infectious and malignant complications of TNF inhibitor therapy in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013; 108:1835–1842. PMID: 24042192.

Article13. Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008; 134:929–936. PMID: 18294633.

Article14. Cottone M, Kohn A, Daperno M, et al. Advanced age is an independent risk factor for severe infections and mortality in patients given anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 9:30–35. PMID: 20951835.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Biological Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children

- Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy in Intestinal Behçet's Disease

- Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus Following Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Therapy

- Rectal tuberculosis after infliximab therapy despite negative screening for latent tuberculosis in a patient with ulcerative colitis

- Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor Agents and Tuberculosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease