Tuberc Respir Dis.

2017 Jan;80(1):27-34. 10.4046/trd.2017.80.1.27.

Duration of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Infectiousness under Adequate Therapy, as Assessed Using Induced Sputum Samples

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. bfspark2@gmail.com

- 2Lung Research Institute, Hallym University College of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 3Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 5Division of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju, Korea.

- KMID: 2396338

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2017.80.1.27

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

A sputum culture is the most reliable indicator of the infectiousness of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB); however, a spontaneous sputum specimen may not be suitable. The aim of this study was to evaluate the infectious period in patients with non-drug-resistant (DR) PTB receiving adequate standard chemotherapy, using induced sputum (IS) specimens.

METHODS

We evaluated the duration of infectiousness of PTB using a retrospective cohort design.

RESULTS

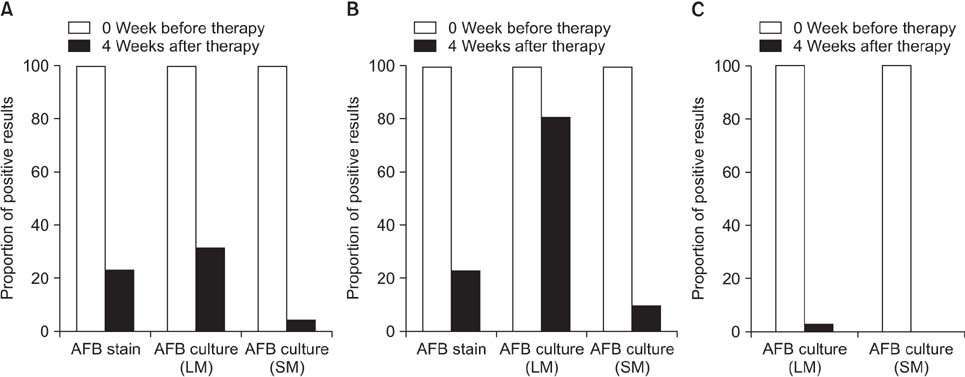

Among the 35 patients with PTB, 22 were smear-positive. The rates of IS culture positivity from baseline to the sixth week of anti-tuberculosis medication in the smear-positive PTB group were 100%, 100%, 91%, 73%, 36%, and 18%, respectively. For smear-positive PTB cases, the median time of conversion to culture negativity was 35.0 days (range, 28.0-42.0 days). In the smear-negative PTB group (n=13), the weekly rates of positive IS culture were 100%, 77%, 39%, 8%, 0%, and 0%, respectively, and the median time to conversion to culture-negative was 21.0 days (range, 17.5-28.0 days).

CONCLUSION

The infectiousness of PTB, under adequate therapy, may persist longer than previously reported, even in patients with non-DR PTB.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Paulson T. Epidemiology: a mortal foe. Nature. 2013; 502:S2–S3.2. Eurosurveillance editorial team. WHO publishes Global tuberculosis report 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013; 18:20615.3. American Thoracic Society. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infectious Diseases Society of America. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005; 172:1169–1227.4. Luna JA. A tubeculosis guide for specialist physicians. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease;2003.5. Riley RL, Mills CC, O'Grady F, Sultan LU, Wittstadt F, Shivpuri DN. Infectiousness of air from a tuberculosis ward: ultraviolet irradiation of infected air: comparative infectiousness of different patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1962; 85:511–525.6. Yeager H Jr, Lacy J, Smith LR, LeMaistre CA. Quantitative studies of mycobacterial populations in sputum and saliva. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967; 95:998–1004.7. Loudon RG, Spohn SK. Cough frequency and infectivity in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1969; 99:109–111.8. Sultan L, Nyka W, Mills C, O'Grady F, Wells W, Riley RL. Tuberculosis disseminators: a study of the variability of aerial infectivity of tuberculous patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1960; 82:358–369.9. Jindani A, Aber VR, Edwards EA, Mitchison DA. The early bactericidal activity of drugs in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980; 121:939–949.10. Brooks SM, Lassiter NL, Young EC. A pilot study concerning the infection risk of sputum positive tuberculosis patients on chemotherapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973; 108:799–804.11. Rouillon A, Perdrizet S, Parrot R. Transmission of tubercle bacilli: the effects of chemotherapy. Tubercle. 1976; 57:275–299.12. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: guidance. Tuberculosis: clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence;2011.13. National Tuberculosis Controllers Association. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious tuberculosis: recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005; 54:1–47.14. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Lung Association. Canadian Thoracic Society. Canadian tuberculosis standards. 7th edition. Ottwa: Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Lung Association, Canadian Thoracic Society;2013.15. Behr MA, Warren SA, Salamon H, Hopewell PC, Ponce de Leon A, Daley CL, et al. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli. Lancet. 1999; 353:444–449.16. Hernandez-Garduno E, Cook V, Kunimoto D, Elwood RK, Black WA, FitzGerald JM. Transmission of tuberculosis from smear negative patients: a molecular epidemiology study. Thorax. 2004; 59:286–290.17. Tostmann A, Kik SV, Kalisvaart NA, Sebek MM, Verver S, Boeree MJ, et al. Tuberculosis transmission by patients with smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in a large cohort in the Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47:1135–1142.18. Fitzwater SP, Caviedes L, Gilman RH, Coronel J, LaChira D, Salazar C, et al. Prolonged infectiousness of tuberculosis patients in a directly observed therapy short-course program with standardized therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2010; 51:371–378.19. Park JS. Efficacy of induced sputum for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in adults unable to expectorate sputum. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2015; 78:203–209.20. Gonzalez-Angulo Y, Wiysonge CS, Geldenhuys H, Hanekom W, Mahomed H, Hussey G, et al. Sputum induction for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012; 31:1619–1630.21. Hepple P, Ford N, McNerney R. Microscopy compared to culture for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in induced sputum samples: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012; 16:579–588.22. Anderson C, Inhaber N, Menzies D. Comparison of sputum induction with fiber-optic bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995; 152:1570–1574.23. Grant LR, Hammitt LL, Murdoch DR, O'Brien KL, Scott JA. Procedures for collection of induced sputum specimens from children. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54:Suppl 2. S140–S145.24. Brown M, Varia H, Bassett P, Davidson RN, Wall R, Pasvol G. Prospective study of sputum induction, gastric washing, and bronchoalveolar lavage for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in patients who are unable to expectorate. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44:1415–1420.25. Geldenhuys HD, Kleynhans W, Buckerfield N, Tameris M, Gonzalez Y, Mahomed H, et al. Safety and tolerability of sputum induction in adolescents and adults with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012; 31:529–537.26. Bae E, Im JH, Kim SW, Yoon NS, Sung H, Kim MN, et al. Evaluation of combination of BACTEC mycobacteria growth indicator tube 960 system and Ogawa media for mycobacterial culture. Korean J Lab Med. 2008; 28:299–306.27. Diagnostic Standards and Classification of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Disease Society of America, September 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 161:1376–1395.28. Yimer SA, Holm-Hansen C, Storla DG, Bjune GA. Tuberculosis management time: an alternative parameter for measuring the tuberculosis infectious pool. Trop Med Int Health. 2014; 19:313–320.29. Senkoro M, Mfinanga SG, Morkve O. Smear microscopy and culture conversion rates among smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients by HIV status in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2010; 10:210.30. Dominguez-Castellano A, Muniain MA, Rodriguez-Bano J, Garcia M, Rios MJ, Galvez J, et al. Factors associated with time to sputum smear conversion in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003; 7:432–438.31. Parikh R, Nataraj G, Kanade S, Khatri V, Mehta P. Time to sputum conversion in smear positive pulmonary TB patients on category I DOTS and factors delaying it. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012; 60:22–26.32. Rueda ZV, Lopez L, Velez LA, Marin D, Giraldo MR, Pulido H, et al. High incidence of tuberculosis, low sensitivity of current diagnostic scheme and prolonged culture positivity in four colombian prisons. A cohort study. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e80592.33. Aoki M. Transmission of tuberculosis (I). Kekkaku. 2004; 79:509–518.34. Hales CM, Heilig CM, Chaisson R, Leung CC, Chang KC, Goldberg SV, et al. The association between symptoms and microbiologically defined response to tuberculosis treatment. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013; 10:18–25.35. Turner RD, Bothamley GH. Cough and the transmission of tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2015; 211:1367–1372.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of Induced Sputum and Bronchoscopy in Diagnosis of Active Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- Observation on sputum cytology in pulmonary tuberculosis

- Comparison of Smear and Culture Positivity using NaOH Method and NALC-NaOH Method for Sputum Treatment

- The Diagnostic Value of Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid microscopic study and PCR in Pulmonary tuberculosis

- Potential Role of Immunodiagnosis for Pulmonary Tuberculosis Using Induced Sputum Cells