J Korean Med Sci.

2017 Sep;32(9):1423-1430. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1423.

Association of Emotional Labor, Self-efficacy, and Type A Personality with Burnout in Korean Dental Hygienists

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, The Graduate School of Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine and Institute of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea. chang0343@yonsei.ac.kr

- 3Department of Dental Hygiene, Wonkwang Health Science University, Iksan, Korea.

- 4Department of Dental Hygiene, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea.

- 5Department of Preventive Medicine and Institute of Occupational Medicine, College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Biostatistics and Computing, The Graduate School of Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2385947

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1423

Abstract

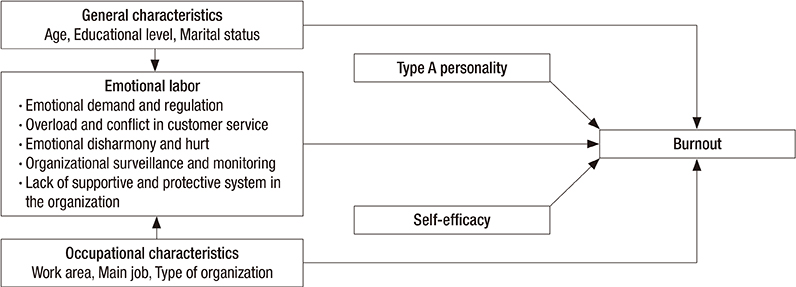

- The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between emotional labor and burnout, and whether the levels of self-efficacy and type A personality characteristics increase the risk of burnout in a sample of Korean female dental hygienists. Participants were 807 female dental hygienists with experience in performing customer service for one year or more in dental clinics, dental hospitals, or general hospitals in Korea. Data were collected using a structured self-administered questionnaire. A hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine the effects of emotional labor on burnout, and to elucidate the additive effects of self-efficacy and type A personality on burnout. The results showed that "overload and conflict in customer service,""emotional disharmony and hurt," and "lack of a supportive and protective system in the organization" were positively associated with burnout. With reference to the relationship between personality traits and burnout, we found that personal traits such as self-efficacy and type A personality were significantly related to burnout, which confirmed the additive effects of self-efficacy and type A personality on burnout. These results indicate that engaging in excessive and prolonged emotional work in customer service roles is more likely to increase burnout. Additionally, an insufficient organizational supportive and protective system toward the negative consequences of emotional labor was found to accelerate burnout. The present findings also revealed that personality traits such as self-efficacy and type A personality are also important in understanding the relationship between emotional labor and burnout.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Mental disorders among workers in the healthcare industry: 2014 national health insurance data

Min-Seok Kim, Taeshik Kim, Dongwook Lee, Ji-hoo Yook, Yun-Chul Hong, Seung-Yup Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon, Mo-Yeol Kang

Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018;30(1):. doi: 10.1186/s40557-018-0244-x.Emotional Labor and Burnout: A Review of the Literature

Da-Yee Jeung, Changsoo Kim, Sei-Jin Chang

Yonsei Med J. 2018;59(2):187-193. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.2.187.Does Emotional Labor Increase the Risk of Suicidal Ideation among Firefighters?

Dae-Sung Hyun, Da-Yee Jeung, Changsoo Kim, Hye-Yoon Ryu, Sei-Jin Chang

Yonsei Med J. 2020;61(2):179-185. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2020.61.2.179.

Reference

-

1. Central Intelligence Agency (US). The World Factbook 2009. Washington, D.C: Central Intelligence Agency;2009.2. Hochschild AR. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press;1983.3. Morris JA, Feldman DC. Managing emotions in the workplace. J Manag Issue. 1997; 9:257–274.4. Zapf D. Emotion work and psychological well-being: a review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2002; 12:237–268.5. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001; 52:397–422.6. Brotheridge CM, Grandey AA. Emotional labor and burnout: comparing two perspectives of “people work”. J Vocat Behav. 2002; 60:17–39.7. Grandey AA. When “the show must go on”: surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Acad Manage J. 2003; 46:86–96.8. Pugliesi K. The consequences of emotional labor: effects on work stress, job satisfaction, and well-being. Motiv Emot. 1999; 23:125–154.9. Le Blanc PM, Hox JJ, Schaufeli WB, Taris TW, Peeters MC. Take care! The evaluation of a team-based burnout intervention program for oncology care providers. J Appl Psychol. 2007; 92:213–227.10. Lee RT, Ashforth BE. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol. 1996; 81:123–133.11. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977; 84:191–215.12. Brown CG. A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy and burnout in teachers. Educ Child Psychol. 2012; 29:47–63.13. Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005; 139:439–457.14. Friedman M, Rosenman RH. Type A Behavior and Your Heart. New York, NY: Fawcett Crest;1974.15. Froggatt KL, Cotton JL. The impact of Type A behavior pattern on role overload-induced stress and performance attributions. J Manage. 1987; 13:87–98.16. Khan S. Relationship of job burnout and Type A behaviour on psychological health among secretaries. Int J Bus Manage. 2011; 6:31–38.17. Korean Health & Medical Workers' Union. Current Status and Situations of Emotional Labor in Korean Health Care Providers: Data from a Survey. Seoul: Korean Health Medical Workers' Union;2010.18. Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (KR). Developing Korean Emotional labor Scale (K-ELS) and Workplace Violence Scale (K-WVS). Ulsan: Korean Occupational Safety and Health Agency;2014.19. Chen G, Gully SM, Eden D. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organ Res Methods. 2001; 4:62–83.20. Haynes SG, Levine S, Scotch N, Feinleib M, Kannel WB. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. I. Methods and risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1978; 107:362–383.21. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981; 2:99–113.22. Howard A. A framework for work change. In : Howard A, editor. The Changing Nature of Work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass;1995. p. 3–44.23. Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Validation of the Maslach burnout inventory-general survey: an internet study. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2002; 15:245–260.24. Schaufeli WB. Past performance and future perspectives of burnout research. SA J Ind Psychol. 2003; 29:1–15.25. Lim SS, Lee W, Hong K, Jeung D, Chang SJ, Yoon JH. Facing complaining customer and suppressed emotion at worksite related to sleep disturbance in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31:1696–1702.26. Yoon JH, Jeung D, Chang SJ. Does high emotional demand with low job control relate to suicidal ideation among service and sales workers in Korea? J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31:1042–1048.27. Yoon JH, Kang MY, Jeung DY, Chang SJ. Suppressing emotion and engaging with complaining customers at work related to experience of depression and anxiety symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Ind Health. 2017; 55:265–274.28. Leiter MP. Burn-out as a crisis in self-efficacy: conceptual and practical implications. Work Stress. 1992; 6:107–115.29. Lee RT, Seo B, Hladkyj S, Lovell BL, Schwartzmann L. Correlates of physician burnout across regions and specialties: a meta-analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2013; 11:48.30. Alarcon G, Eschleman KJ, Bowling NA. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: a meta-analysis. Work Stress. 2009; 23:244–263.31. Soria MS, Gumbau RG, Peiro JM. New Technologies and Continuous Training in the Company: a Psychosocial Study. Castelló de la Plana: Publicaciones Universitat Jaume I;2001.32. Pick D, Leiter MP. Nurses’ perceptions of burnout: a comparison of self-reports and standardized measures. Can J Nurs Res. 1991; 23:33–48.33. Kirmeyer SL. Coping with competing demands: interruption and the Type A pattern. J Appl Psychol. 1988; 73:621–629.34. Spector PE, O'Connell BJ. The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1994; 67:1–12.35. Caplan RD, Jones KW. Effects of work load, role ambiguity, and Type A personality on anxiety, depression, and heart rate. J Appl Psychol. 1975; 60:713–719.36. Burke RJ, Deszca E. Preferred organizational climates of Type A individuals. J Vocat Behav. 1982; 21:50–59.37. Burke RJ, Greenglass E. A longitudinal study of psychological burnout in teachers. Hum Relat. 1995; 48:187–202.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The effects of emotional labor on burnout, turnover intention, and job satisfaction among clinical dental hygienists

- Emotional Labor and Burnout: A Review of the Literature

- A study on Burnout, Emotional labor, and Self-efficacy in Nurses

- Influences of Type D Personality, Positive Psychological Capital, and Emotional Labor on the Burnout of Psychiatric Nurses

- A Scoping Review on Burnout among Dental Hygienists in South Korea