J Nutr Health.

2017 Feb;50(1):53-63. 10.4163/jnh.2017.50.1.53.

Comparison of sweetness preference and motivational factors between Korean and Japanese children

- Affiliations

-

- 1Graduate School of Nutrition and Health Sciences, Undergraduate School of Nutrition Sciences, Kagawa Nutrition University, Sakado, 350-0214, Japan.

- 2Department of Food and Nutrition, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea. jung77e@changwon.ac.kr

- KMID: 2377981

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4163/jnh.2017.50.1.53

Abstract

- PURPOSE

This study was performed to examine motivational factors affecting sweetness preference in Korean and Japanese children. We identified meaningful variables that could be targeted to nutrition education interventions designed to overcome innate barriers and reduce sweetness preference and sweet food intake in Korean and Japanese children.

METHODS

Questionnaire surveys and sweetness preference test were conducted to examine variables affecting behavioral intention (BI) regarding sweetness preference. Questionnaire variables were based on the theory of planned behavior. Participants were recruited from one urban school from each country. In total, 166 children (mean age: 8.4 years) and their guardians (n = 166) participated in the study. A trained research assistant provided all children with personal guidance regarding completion of the sweetness preference test and survey questionnaire at school. The data were analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficients, t tests, repeated measure ANOVA, and stepwise multiple regression analysis (significance level: p < 0.05).

RESULTS

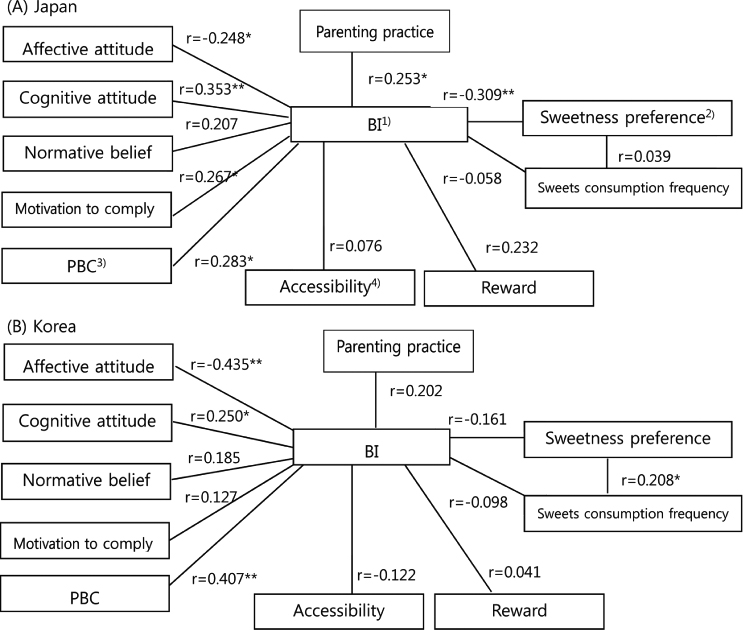

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) and parenting practice were significantly associated with BI in both groups. Motivation to comply affected BI only in Japanese children, whereas affective attitude was associated with BI only in Korean children. In predicting sweetness preference, BI was associated only in Japanese children, whereas sweets consumption frequency had a significant effect in Korean children.

CONCLUSION

The study shows similarities and differences in motivational factors, which could be considered when developing nutrition education programs in Korea and Japan. PBC and parenting practice were common factors in predicting BI. In predicting sweetness preference, BI had a significant effect on Japanese children, whereas sweets consumption frequency was the greatest contributor in Korean children.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Exploring parenting variables associated with sweetness preferences and sweets intake of children

Taejung Woo, Kyung-Hea Lee

Nutr Res Pract. 2019;13(2):169-177. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2019.13.2.169.

Reference

-

1. Contento IR. Nutrition education: linking research, theory, and practice. 3rd ed. Burlington (MA): Jones & Bartlett Learning;2016.2. Drewnowski A, Mennella JA, Johnson SL, Bellisle F. Sweetness and food preference. J Nutr. 2012; 142(6):1142S–1148S.

Article3. Kim SH, Chung HK. Sugar supply and intake of Koreans. Korean J Nutr. 2007; 40:Suppl. 22–28.4. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (KR). Increased sugar intake through processed foods [Internet]. Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety;2014. 09. 23. cited 2016 Apr 1. Available from: http://www.mfds.go.kr/index.do?mid=675&pageNo=89&seq=25171&sitecode=1&cmd=v.5. Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004; 79(4):537–543.

Article6. Reed DR, McDaniel AH. The human sweet tooth. BMC Oral Health. 2006; 6:Suppl 1. S17.

Article7. Son HN, Park MJ, Han JS. A study on dietary habits and food frequency of young children who like sweets. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2009; 15(1):10–21.8. Baik I, Lee M, Jun NR, Lee JY, Shin C. A healthy dietary pattern consisting of a variety of food choices is inversely associated with the development of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res Pract. 2013; 7(3):233–241.

Article9. Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999; 19(1):41–62.

Article10. Zoellner J, Estabrooks PA, Davy BM, Chen YC, You W. Exploring the theory of planned behavior to explain sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012; 44(2):172–177.

Article11. Conner M, Norman P, Bell R. The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychol. 2002; 21(2):194–201.

Article12. Rozin P, Fischler C, Imada S, Sarubin A, Wrzesniewski A. Attitudes to food and the role of food in life in the U.S.A., Japan, Flemish Belgium and France: possible implications for the diet-health debate. Appetite. 1999; 33(2):163–180.

Article13. Knof K, Lanfer A, Bildstein MO, Buchecker K, Hilz H. IDEFICS Consortium. Development of a method to measure sensory perception in children at the European level. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011; 35:Suppl 1. S131–S136.

Article14. Roininen K, Tuorila H, Zandstra EH, de Graaf C, Vehkalahti K, Stubenitsky K, Mela DJ. Differences in health and taste attitudes and reported behaviour among Finnish, Dutch and British consumers: a cross-national validation of the Health and Taste Attitude Scales (HTAS). Appetite. 2001; 37(1):33–45.

Article15. Brug J, Tak NI, te Velde SJ, Bere E, de Bourdeaudhuij I. Taste preferences, liking and other factors related to fruit and vegetable intakes among schoolchildren: results from observational studies. Br J Nutr. 2008; 99:Suppl 1. S7–S14.

Article16. Lanfer A, Bammann K, Knof K, Buchecker K, Russo P, Veidebaum T, Kourides Y, De Henauw S, Molnar D, Bel-Serrat S, Lissner L, Ahrens W. Predictors and correlates of taste preferences in European children: the IDEFICS study. Food Qual Prefer. 2013; 27(2):128–136.

Article17. Estima CC, Bruening M, Hannan PJ, Alvarenga MS, Leal GV, Philippi ST, Neumark-Sztainer D. A cross-cultural comparison of eating behaviors and home food environmental factors in adolescents from São Paulo (Brazil) and Saint Paul-Minneapolis (US). J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014; 46(5):370–375.

Article18. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD data: life expectancy at birth [Internet]. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development;2015. cited 2015 Dec 31. Available from: http://data.oecd.org/healthstat/lifeexpectancy-at-birth.htm.19. Takeichi H, Taniguchi H, Fukinbara M, Tanaka N, Shikanai S, Sarukura N, Hsu TF, Wong Y, Yamamoto S. Sugar intakes from snacks and beverages in Japanese children. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2012; 58(2):113–117.

Article20. Shikanai S, Koung Ry L, Takeichi H, Emiko S, San P, Sarukura N, Kamoshita S, Yamamoto S. Sugar intake and body weight in Cambodian and Japanese children. J Med Invest. 2014; 61(1-2):72–78.

Article21. Liem DG, Mars M, De Graaf C. Sweet preferences and sugar consumption of 4- and 5-year-old children: role of parents. Appetite. 2004; 43(3):235–245.

Article22. Kampov-Polevoy AB, Alterman A, Khalitov E, Garbutt JC. Sweet preference predicts mood altering effect of and impaired control over eating sweet foods. Eat Behav. 2006; 7(3):181–187.

Article23. Kobayashi T, Tanaka S, Toji C, Shinohara H, Kamimura M, Okamoto N, Imai S, Fukui M, Date C. Development of a food frequency questionnaire to estimate habitual dietary intake in Japanese children. Nutr J. 2010; 9(1):17.

Article24. Kang MH, Yoon KS. Elementary school students’ amounts of sugar, sodium, and fats exposure through intake of processed food. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2009; 38(1):52–61.

Article25. Bazillier C, Verlhiac JF, Mallet P, Rouëssé J. Predictors of intentions to eat healthily in 8-9-year-old children. J Cancer Educ. 2011; 26(3):572–576.

Article26. Musher-Eizenman D, Holub S. Comprehensive feeding practice questionnaire: validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007; 32(8):960–972.27. Woo T, Lee KH. Relationship between sweet preferences and motivation factors of 2nd grade schoolchildren. Korean J Food Nutr. 2014; 27(3):383–392.28. Matsushita Y, Mizoue T, Takahashi Y, Isogawa A, Kato M, Inoue M, Noda M, Tsugane S. JPHC Study Group. Taste preferences and body weight change in Japanese adults: the JPHC study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009; 33(10):1191–1197.

Article29. Faith MS. Development and modification of child food preferences and eating patterns: behavior genetics strategies. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005; 29(6):549–556.

Article30. Scaglioni S, Arrizza C, Vecchi F, Tedeschi S. Determinants of children's eating behavior. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011; 94:6 Suppl. 2006S–2011S.

Article31. Eisenberg CM, Ayala GX, Crespo NC, Lopez NV, Zive MM, Corder K, Wood C, Elder JP. Examining multiple parenting behaviors on young children's dietary fat consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012; 44(4):302–309.

Article32. Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to palatable foods affects children's behavioral response, food selection, and intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999; 69(6):1264–1272.

Article33. Margolis H, McCabe PP. Improving self-efficacy and motivation: what to do, what to say. Interv Sch Clin. 2006; 41(4):218–227.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Erratum: Authorship Correction. Comparison of sweetness preference and motivational factors between Korean and Japanese children

- Exploring parenting variables associated with sweetness preferences and sweets intake of children

- Using Motivational Interviewing in Diabetes Self-Management Education

- Factors influencing the career preferences of medical students and interns: a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey from India

- The Effect of Lifestyle, Dietary Habit, Food Preference and Eating Frequency on Sweet Taste Sensitivity and Preference of the Middle School Students