Korean J Ophthalmol.

2015 Apr;29(2):102-108. 10.3341/kjo.2015.29.2.102.

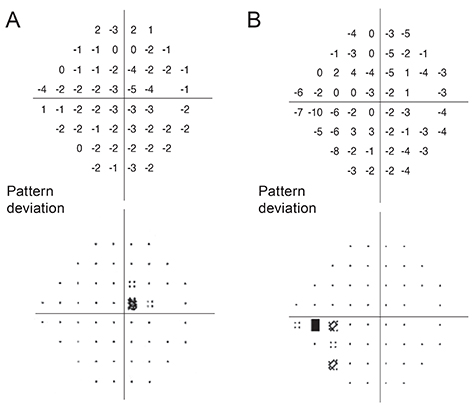

Comparison of Risk Factors for Initial Central Scotoma versus Initial Peripheral Scotoma in Normal-tension Glaucoma

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Konkuk University Medical Center, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. bjcho@kuh.ac.kr

- KMID: 2363715

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2015.29.2.102

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the risk factors for initial central scotoma (ICS) compared with initial peripheral scotoma (IPS) in normal-tension glaucoma (NTG).

METHODS

Fifty-six NTG patients (56 eyes) with an ICS and 103 NTG patients (103 eyes) with an IPS were included. Retrospectively, the differences were assessed between the two groups for baseline characteristics, ocular factors, systemic factors, and lifestyle factors. Also, the mean deviation of visual field was compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

Patients from both ICS and IPS groups were of similar age, gender, family history of glaucoma, and follow-up periods. Frequency of disc hemorrhage was significantly higher among patients with ICS than in patients with IPS. Moreover, systemic risk factors such as hypotension, migraine, Raynaud's phenomenon, and snoring were more prevalent in the ICS group than in the IPS group. There were no statistical differences in lifestyle risk factors such as smoking or body mass index. Pattern standard deviation was significantly greater in the ICS group than in the IPS group, but the mean deviation was similar between the two groups.

CONCLUSIONS

NTG Patients with ICS and IPS have different profiles of risk factors and clinical characteristics. This suggests that the pattern of initial visual field loss may be useful to identify patients at higher risk of central field loss.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Association between Corneal Biomechanical Properties and Initial Visual Field Defect Pattern in Normal Tension Glaucoma

Bo Ram Lee, Kyung Eun Han, Kyu Ryong Choi

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2017;58(2):178-184. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2017.58.2.178.

Reference

-

1. Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90:262–267.2. Berenson K, Kymes S, Walt JG, Siegartel LR. The relationship of mean deviation scores and resource utilization among patients with glaucoma: a retrospective United States and European chart review analysis. J Glaucoma. 2009; 18:390–394.3. Kamal D, Hitchings R. Normal tension glaucoma: a practical approach. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998; 82:835–840.4. Iwase A, Suzuki Y, Araie M, et al. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in Japanese: the Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:1641–1648.5. Pekmezci M, Vo B, Lim AK, et al. The characteristics of glaucoma in Japanese Americans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009; 127:167–171.6. Kim CS, Seong GJ, Lee NH, et al. Prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in central South Korea the Namil study. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1024–1030.7. Flammer J, Mozaffarieh M. What is the present pathogenetic concept of glaucomatous optic neuropathy? Surv Ophthalmol. 2007; 52:Suppl 2. S162–S173.8. Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998; 126:487–497.9. Flammer J, Orgul S, Costa VP, et al. The impact of ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002; 21:359–393.10. Demailly P, Cambien F, Plouin PF, et al. Do patients with low tension glaucoma have particular cardiovascular characteristics? Ophthalmologica. 1984; 188:65–75.11. Tielsch JM, Katz J, Sommer A, et al. Hypertension, perfusion pressure, and primary open-angle glaucoma: a population-based assessment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995; 113:216–221.12. Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, et al. High prevalence of glaucoma in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:1009–1012.13. Lee AJ, Rochtchina E, Wang JJ, et al. Does smoking affect intraocular pressure? Findings from the Blue Mountains Eye Study. J Glaucoma. 2003; 12:209–212.14. Renard JP, Rouland JF, Bron A, et al. Nutritional, lifestyle and environmental factors in ocular hypertension and primary open-angle glaucoma: an exploratory case-control study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013; 91:505–513.15. Pasquale LR, Kang JH. Lifestyle, nutrition, and glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2009; 18:423–428.16. Kolker AE. Visual prognosis in advanced glaucoma: a comparison of medical and surgical therapy for retention of vision in 101 eyes with advanced glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1977; 75:539–555.17. Nah YS, Seong GJ, Kim CY. Visual function and quality of life in Korean patients with glaucoma. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2002; 16:70–74.18. Wiggs JL, Hewitt AW, Fan BJ, et al. The p53 codon 72 PRO/PRO genotype may be associated with initial central visual field defects in caucasians with primary open angle glaucoma. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e45613.19. Buys ES, Ko YC, Alt C, et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase α1-deficient mice: a novel murine model for primary open angle glaucoma. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e60156.20. Park SC, De Moraes CG, Teng CC, et al. Initial parafoveal versus peripheral scotomas in glaucoma: risk factors and visual field characteristics. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1782–1789.21. Coeckelbergh TR, Brouwer WH, Cornelissen FW, et al. The effect of visual field defects on driving performance: a driving simulator study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002; 120:1509–1516.22. Fujita K, Yasuda N, Oda K, Yuzawa M. Reading performance in patients with central visual field disturbance due to glaucoma. Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2006; 110:914–918.23. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983; 67:818–821.24. Caprioli J, Spaeth GL. Comparison of visual field defects in the low-tension glaucomas with those in the high-tension glaucomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984; 97:730–737.25. Thonginnetra O, Greenstein VC, Chu D, et al. Normal versus high tension glaucoma: a comparison of functional and structural defects. J Glaucoma. 2010; 19:151–157.26. Uhler TA, Piltz-Seymour J. Optic disc hemorrhages in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: implications and recommendations. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008; 19:89–94.27. Healey PR, Mitchell P, Smith W, Wang JJ. Optic disc hemorrhages in a population with and without signs of glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105:216–223.28. Budenz DL, Anderson DR, Feuer WJ, et al. Detection and prognostic significance of optic disc hemorrhages during the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113:2137–2143.29. Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, et al. Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:1965–1972.30. Drance S, Anderson DR, Schulzer M. Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Risk factors for progression of visual field abnormalities in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001; 131:699–708.31. Siegner SW, Netland PA. Optic disc hemorrhages and progression of glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103:1014–1024.32. Feke GT, Pasquale LR. Retinal blood flow response to posture change in glaucoma patients compared with healthy subjects. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:246–252.33. Grieshaber MC, Terhorst T, Flammer J. The pathogenesis of optic disc splinter haemorrhages: a new hypothesis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006; 84:62–68.34. Mozaffarieh M, Grieshaber MC, Flammer J. Oxygen and blood flow: players in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2008; 14:224–233.35. Anstead M, Phillips B. The spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing. Respir Care Clin N Am. 1999; 5:363–377.36. Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, et al. Normal-tension glaucoma is associated with sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmologica. 2002; 216:180–184.37. Karakucuk S, Goktas S, Aksu M, et al. Ocular blood flow in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008; 246:129–134.38. Wilson MR, Hertzmark E, Walker AM, et al. A case-control study of risk factors in open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987; 105:1066–1071.39. Ramdas WD, Wolfs RC, Hofman A, et al. Lifestyle and risk of developing open-angle glaucoma: the Rotterdam study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011; 129:767–772.40. Klein BE, Klein R, Ritter LL. Relationship of drinking alcohol and smoking to prevalence of open-angle glaucoma: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1993; 100:1609–1613.41. Edwards R, Thornton J, Ajit R, et al. Cigarette smoking and primary open angle glaucoma: a systematic review. J Glaucoma. 2008; 17:558–566.42. Gasser P, Stumpfig D, Schotzau A, et al. Body mass index in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 1999; 8:8–11.43. Leske MC, Connell AM, Wu SY, et al. Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995; 113:918–924.44. Pasquale LR, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Kang JH. Anthropometric measures and their relation to incident primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:1521–1529.45. Zang EA, Wynder EL. The association between body mass index and the relative frequencies of diseases in a sample of hospitalized patients. Nutr Cancer. 1994; 21:247–261.46. Amerasinghe N, Wong TY, Wong WL, et al. Determinants of the optic cup to disc ratio in an Asian population: the Singapore Malay Eye Study (SiMES). Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126:1101–1108.47. Zheng Y, Cheung CY, Wong TY, et al. Influence of height, weight, and body mass index on optic disc parameters. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51:2998–3002.48. Cho HK, Lee J, Lee M, Kee C. Initial central scotomas vs peripheral scotomas in normal-tension glaucoma: clinical characteristics and progression rates. Eye (Lond). 2014; 28:303–311.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Association between Corneal Biomechanical Properties and Initial Visual Field Defect Pattern in Normal Tension Glaucoma

- Visual Field Change in Normal Tension Glaucoma

- Visual Field Progression in Patients with Primary Open Angle Glaucoma, Normal Tension Glaucoma, and Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma

- Analysis of Factors Related of Location of Initial Visual Field Defect in Normal Tension Glaucoma

- The Effectiveness of Visual Field C10-2 in the Early Detection of Glaucoma with Parafoveal Scotoma