J Korean Soc Spine Surg.

2016 Sep;23(3):183-187. 10.4184/jkss.2016.23.3.183.

Multifocal Extensive Spinal Tuberculosis Accompanying Isolated Involvement of Posterior Elements: A Case Report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Korea. ajh329@gmail.com

- KMID: 2353910

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4184/jkss.2016.23.3.183

Abstract

- STUDY DESIGN: A case report.

OBJECTIVES

To report a rare case of atypical spinal tuberculosis. SUMMARY OF LITERATURE REVIEW: In spinal tuberculosis, non-contiguous multifocal involvement and isolated involvement of posterior elements of the spine have been considered atypical features. There have been a few reports of each of these atypical features but no reports have described spinal tuberculosis with both of these atypical features.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

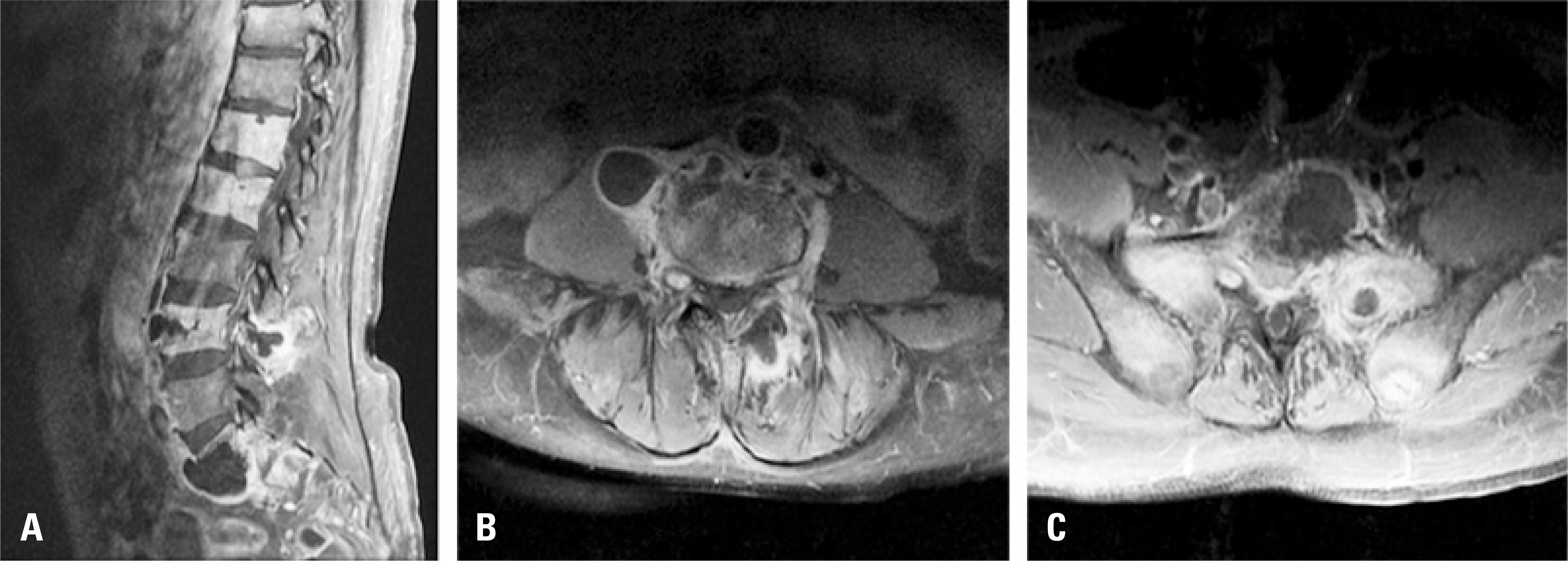

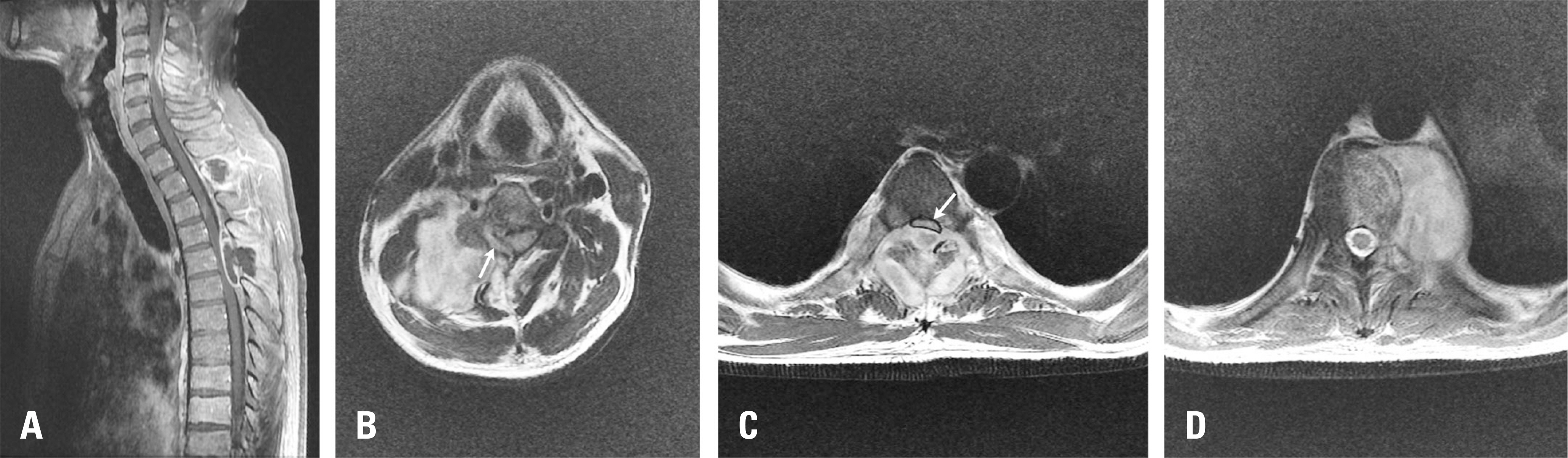

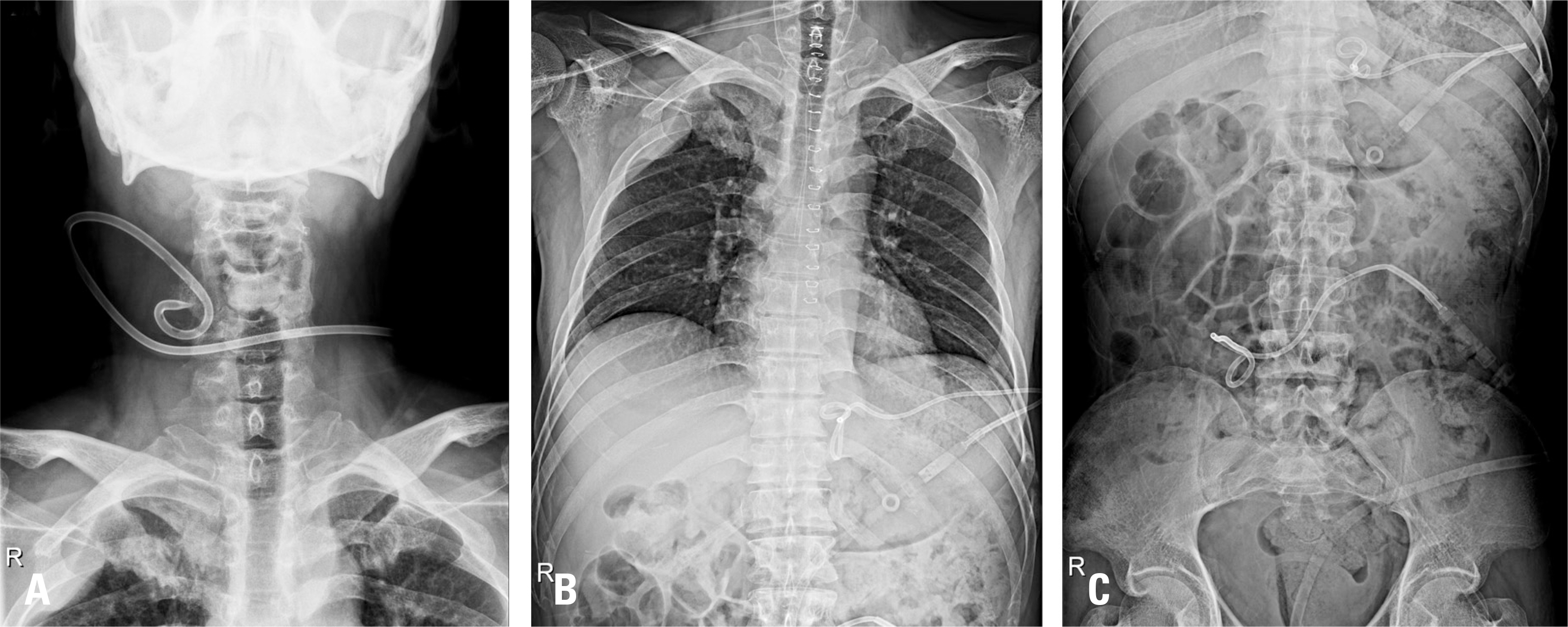

A 39-year-old man presented with back pain and progressive weakness of both lower extremities. He was diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis from the cervical to sacral spine, showing multifocal non-contiguous involvement with multiple abscesses on magnetic resonance imaging. Notably, in the thoracic spine area, isolated involvement of posterior elements was found with an epidural abscess compressing the spinal cord. He underwent a total laminectomy of the thoracic spine and multiple abscesses were drained with pigtail catheter insertions into the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine.

RESULTS

At the 8-month follow-up, the patient's neurologic status had improved to Frankel Grade D, and the patient was able to walk with the support of a walker. At the 3-year follow-up, the patient had recovered completely without any neurologic deficit.

CONCLUSIONS

Since atypical spinal tuberculosis may show various patterns, examination of the entire spine is important for early diagnosis. Treatment should be provided properly from minimally invasive procedures to open surgery depending on the extent of structural instability and neurologic deficit.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Harry N. Herkowitz, Steven R Garfin, Frank J. Eismont, et al. Rothman-Simeone the spine: expert consult. 6th ed.Elsevier Health Sciences:;2011. 1535.2. Lolge S, Maheshwari M, Shah J, et al. Isolated solitary vertebral body tuberculosis—study of seven cases. Clin Radiol. 2003; 58:545–50.

Article3. Wellons JC, Zomorodi AR, Villaviciencio AT, et al. Sacral tuberculosis: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004; 61:136–9.

Article4. Al-Arabi KM, Khan FA. Atypical forms of spinal tuberculosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1987; 88:26–33.5. Sankaran-Kutty M. Atypical tuberculous spondylitis. Int Orthop. 1992; 16:69–74.

Article6. Emel E, Gü zey FK, Gü zey D, et al. Non-contiguous multifocal spinal tuberculosis involving cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral segments: a case report. Eur Spine J. 2006; 15:1019–24.

Article7. Pieri S, Agresti P, Altieri AM, et al. Percutaneous management of complications of tuberculous spondylodiscitis: short-to medium-term results. Radiol Med. 2009; 114:984–95.8. Turgut M. Multifocal extensive spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) involving cervical, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. Br J Neurosurg. 2001; 15:142–6.

Article9. Arora S, Sabat D, Maini L, et al. Isolated involvement of the posterior elements in spinal tuberculosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012; 94:E151.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Multifocal Pott's Disease: A Report of Two Cases

- Tuberculous Epididymo-Orchitis with Multifocal Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis: a Case Report

- Atypical tuberculosis of the spine

- Atypical Form of Multiple Spinal Tuberculosis

- Atypical Presentation of Spinal Tuberculosis Misadiagnosed as Metastatic Spine Tumor