J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2016 Apr;42(2):67-76. 10.5125/jkaoms.2016.42.2.67.

Dracunculiasis in oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Oral and Maxillofacial Microvascular Reconstruction Lab, Sunyani Regional Hospital, Sunyani, Brong Ahafo, Ghana. smin5@snu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dental Research Institute, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2351728

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2016.42.2.67

Abstract

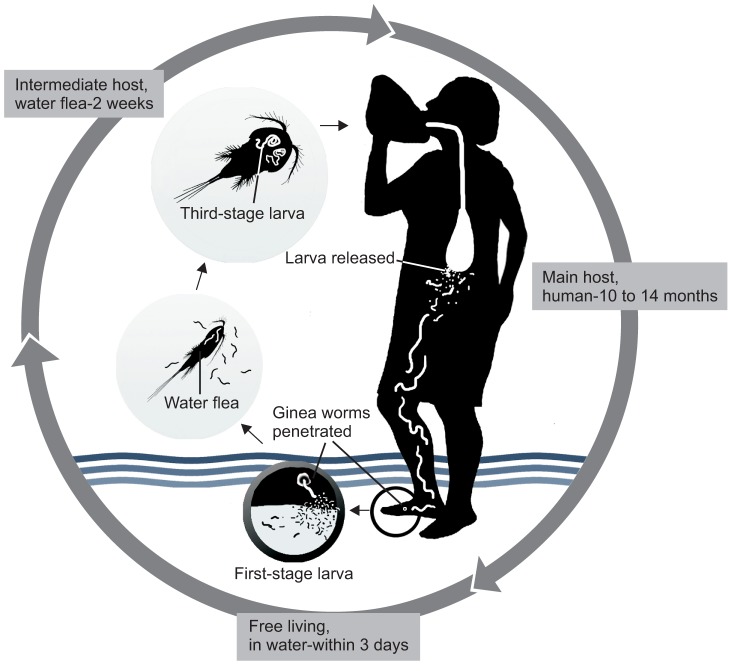

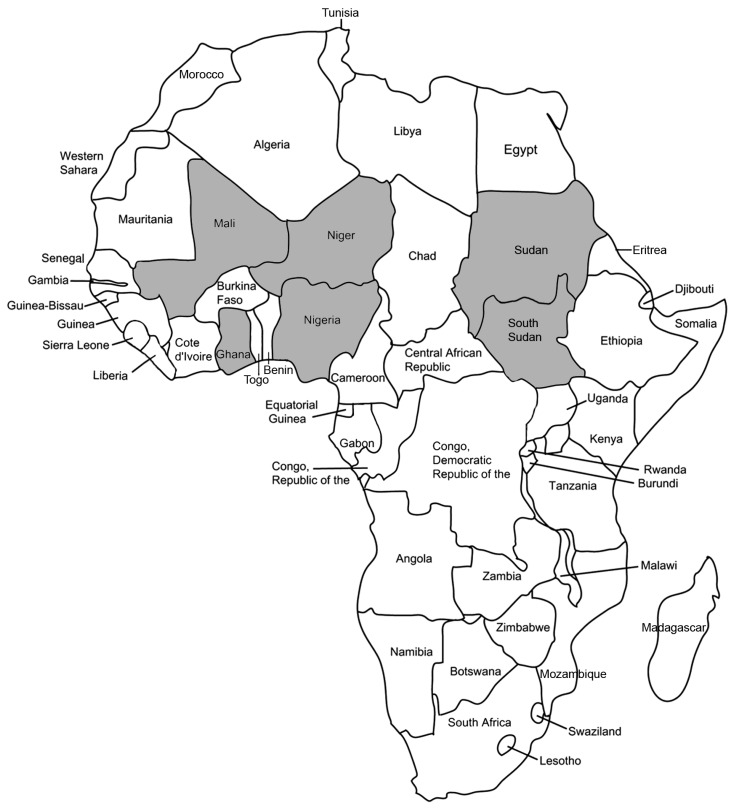

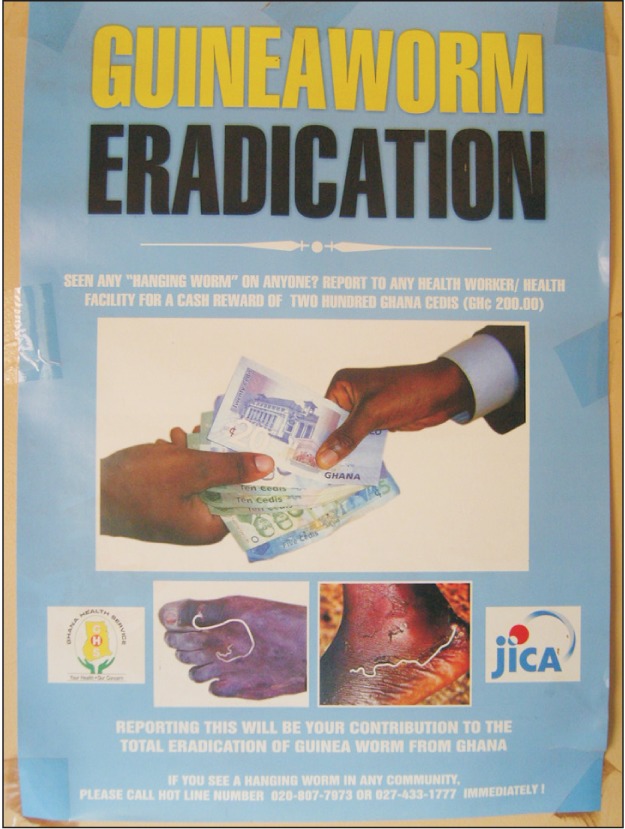

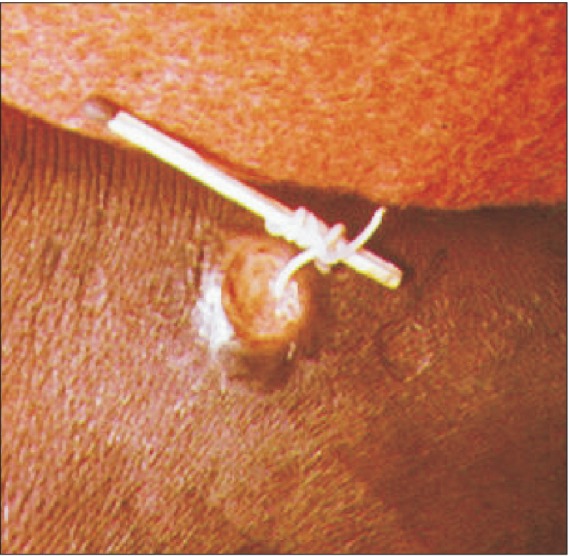

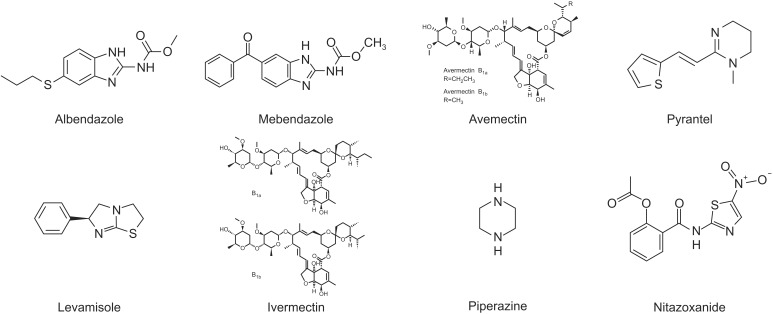

- Dracunculiasis, otherwise known as guinea worm disease (GWD), is caused by infection with the nematode Dracunculus medinensis. This nematode is transmitted to humans exclusively via contaminated drinking water. The transmitting vectors are Cyclops copepods (water fleas), which are tiny free-swimming crustaceans usually found abundantly in freshwater ponds. Humans can acquire GWD by drinking water that contains vectors infected with guinea worm larvae. This disease is prevalent in some of the most deprived areas of the world, and no vaccine or medicine is currently available. International efforts to eradicate dracunculiasis began in the early 1980s. Most dentists and maxillofacial surgeons have neglected this kind of parasite infection. However, when performing charitable work in developing countries near the tropic lines or other regions where GWD is endemic, it is important to consider GWD in cases of swelling or tumors of unknown origin. This paper reviews the pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical criteria, diagnostic criteria, treatment, and prevention of dracunculiasis. It also summarizes important factors for maxillofacial surgeons to consider.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ruiz-Tiben E, Hopkins DR. Helminthic diseases: dracunculiasis. In : Heggenhougen K, Quah SR, editors. International encyclopedia of public health. Oxford: Elsevier;2008. p. 294–311.2. Hunter JM. An introduction to guinea worm on the eve of its departure: dracunculiasis transmission, health effects, ecology and control. Soc Sci Med. 1996; 43:1399–1425. PMID: 8913009.

Article3. Fenwick A. Waterborne infectious diseases--could they be consigned to history? Science. 2006; 313:1077–1081. PMID: 16931751.

Article4. Kappagoda S, Ioannidis JP. Neglected tropical diseases: survey and geometry of randomised evidence. BMJ. 2012; 345:e6512. PMID: 23089149.

Article5. Muller R. Guinea worm disease--the final chapter? Trends Parasitol. 2005; 21:521–524. PMID: 16150643.6. Behbehani K. Candidate parasitic diseases. Bull World Health Organ. 1998; 76(Suppl 2):64–67. PMID: 10063677.7. Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Downs P, Withers PC Jr, Roy S. Dracunculiasis eradication: neglected no longer. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 79:474–479. PMID: 18840732.

Article8. Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E. Strategies for dracunculiasis eradication. Bull World Health Organ. 1991; 69:533–540. PMID: 1835673.9. Dracunculiasis eradication--global surveillance summary, 2008. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009; 84:162–171. PMID: 19425252.10. Poli F. Differential diagnosis of facial acne on black skin. Int J Dermatol. 2012; 51(Suppl 1):24–26. PMID: 23210948.

Article11. Brandt FH, Eberhard ML. Distribution, behavior, and course of patency of Dracunculus insignis in experimentally infected ferrets. J Parasitol. 1990; 76:515–518. PMID: 2143224.

Article12. World Health Organization (WHO). Sustaining the drive to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: second WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: WHO;2013.13. Ruiz-Tiben E, Hopkins DR. Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication. Adv Parasitol. 2006; 61:275–309. PMID: 16735167.

Article14. Al-Awadi AR, Al-Kuhlani A, Breman JG, Doumbo O, Eberhard ML, Guiguemde RT, et al. Guinea worm (Dracunculiasis) eradication: update on progress and endgame challenges. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014; 108:249–251. PMID: 24699360.

Article15. Callahan K, Bolton B, Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Withers PC, Meagley K. Contributions of the Guinea worm disease eradication campaign toward achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7:e2160. PMID: 23738022.

Article16. Google image search: "ascaris worm" [Internet]. cited 2016 Mar 24. Available from: https://www.google.com.gh/search?q=ascaris+worm&biw=1192&bih=933&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&sqi=2&ved=0ahUKEwjLgOmqpYbLAhVL7RQKHbSgD9UQ_AUIBigB#imgrc=jt4vMsn_cowbnM%3A.17. Watts SJ. Dracunculiasis in Africa in 1986: its geographic extent, incidence, and at-risk population. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987; 37:119–125. PMID: 2955710.

Article18. Schneider MC, Aguilera XP, Barbosa da Silva Junior J, Ault SK, Najera P, Martinez J, et al. Elimination of neglected diseases in latin america and the Caribbean: a mapping of selected diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011; 5:e964. PMID: 21358810.

Article19. Callaway E. Dogs thwart effort to eradicate Guinea worm. Nature. 2016; 529:10–11. PMID: 26738575.

Article20. Dracunculiasis eradication. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004; 79:234–235. PMID: 15227956.21. Guinea worm wrap-up #192 [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;cited 2009 Sep 30. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/dracunculiasis/moreinfo_dracunculiasis.htm#wrap.22. Edungbola LD, Withers PC Jr, Braide EI, Kale OO, Sadiq LO, Nwobi BC, et al. Mobilization strategy for guinea worm eradication in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992; 47:529–538. PMID: 1449193.

Article23. Morenikeji O, Asiatu A. Progress in dracunculiasis eradication in Oyo state, South-west Nigeria: a case study. Afr Health Sci. 2010; 10:297–301. PMID: 21327143.24. Miri ES, Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Keana AS, Withers PC Jr, Anagbogu IN, et al. Nigeria's triumph: dracunculiasis eradicated. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010; 83:215–225. PMID: 20682859.

Article25. Hunter JM. Bore holes and the vanishing of guinea worm disease in Ghana's upper region. Soc Sci Med. 1997; 45:71–89. PMID: 9203273.

Article26. Hopkins DR, Withers PC Jr. Sudan's war and eradication of dracunculiasis. Lancet. 2002; 360(Suppl):S21–S22. PMID: 12504489.

Article27. Tayeh A, Cairncross S, Maude GH. The impact of health education to promote cloth filters on dracunculiasis prevalence in the northern region, Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 1996; 43:1205–1211. PMID: 8903124.

Article28. Tayeh A, Cairncross S, Maude GH. Water sources and other determinants of dracunculiasis in the northern region of Ghana. J Helminthol. 1993; 67:213–225. PMID: 8288853.

Article29. Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, Wu W, Anderson PJ, Rochon PA. Oral drug therapy for multiple neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007; 298:1911–1924. PMID: 17954542.30. Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008; 299:1937–1948. PMID: 18430913.

Article31. Cupp EW, Sauerbrey M, Richards F. Elimination of human onchocerciasis: history of progress and current feasibility using ivermectin(Mectizan(®)) monotherapy. Acta Trop. 2011; 120(Suppl 1):S100–S108. PMID: 20801094.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Fourth Industrial Revolution and oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Advanced scope of Korean oral and maxillofacial surgery

- The importance of information technology for clinical and basic researches on the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery

- The application of three-dimensional printing techniques in the fi eld of oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Like & share: video-based learning through social media in oral & maxillofacial surgery