Hanyang Med Rev.

2016 Aug;36(3):192-202. 10.7599/hmr.2016.36.3.192.

Ocular Inflammation Associated with Systemic Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. ophthalmo@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 2350371

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7599/hmr.2016.36.3.192

Abstract

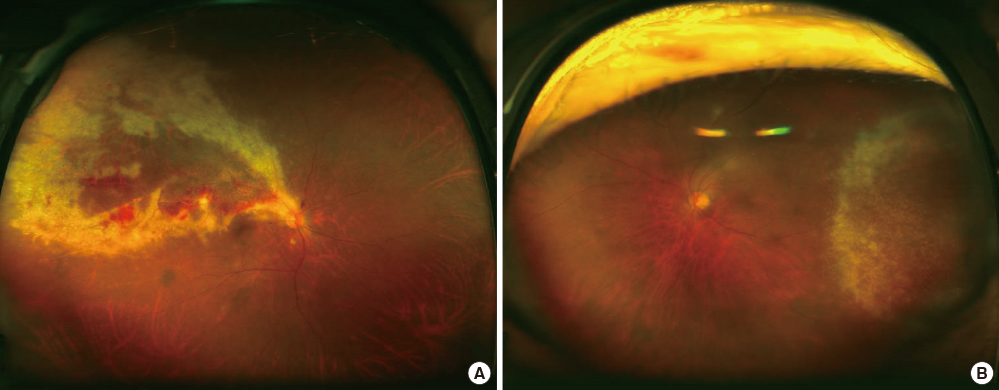

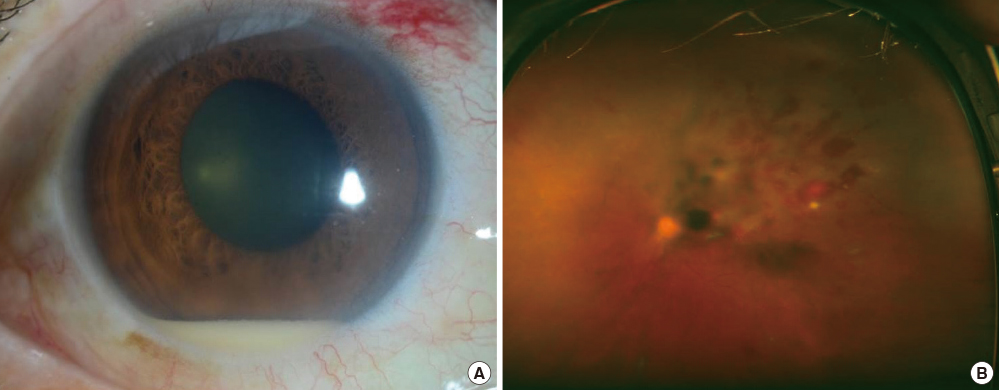

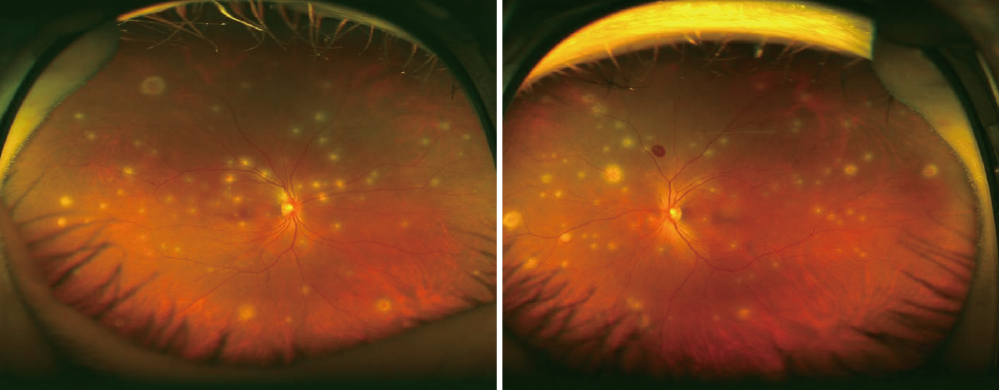

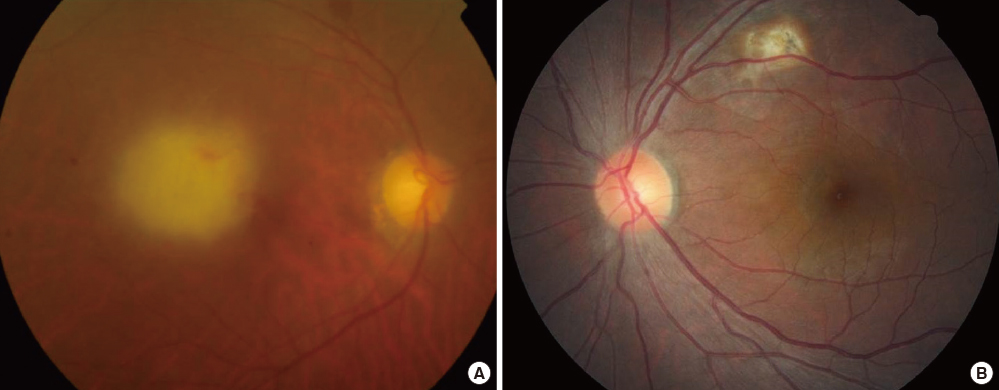

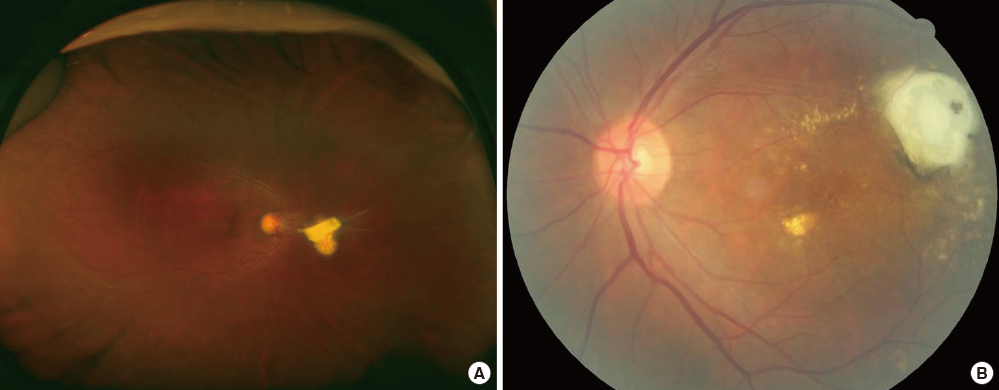

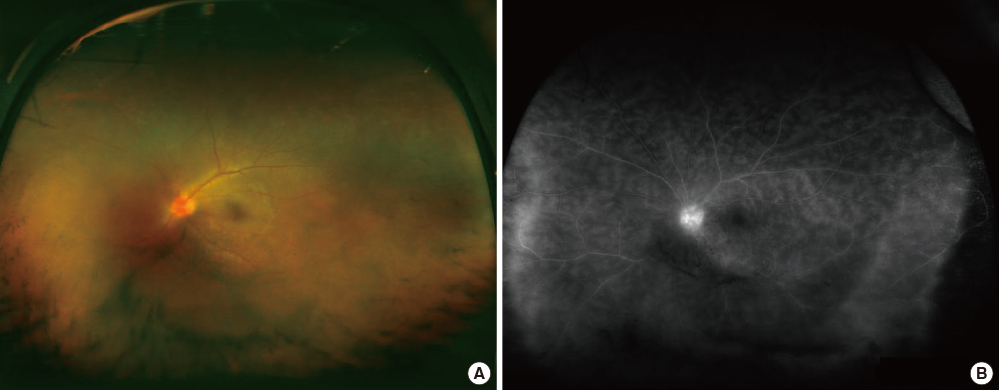

- Systemic infections that are caused by various types of pathogenic organisms can be spread to the eyes as well as to other solid organs. Bacteria, parasites, and viruses can invade the eyes via the bloodstream. Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of systemic infections, many patients still suffer from endogenous ocular infections; this is particularly due to an increase in the number of immunosuppressed patients such as those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, those who have had organ transplantations, and those being administered systemic chemotherapeutic and immunomodulating agents, which may increase the chance of ocular involvement. In this review, we clinically evaluated posterior segment manifestations in the eye caused by hematogenous penetration of systemic infections. We focused on the conditions that ophthalmologists encounter most often and that require cooperation with other medical specialists. Posterior segment manifestations and clinical characteristics of cytomegalovirus retinitis, endogenous endophthalmitis, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, and ocular syphilis are included in this brief review.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Diseases: The Eyes are the Windows of the Body

Heeyoon Cho

Hanyang Med Rev. 2016;36(3):143-145. doi: 10.7599/hmr.2016.36.3.143.

Reference

-

1. Gallant JE, Moore RD, Richman DD, Keruly J, Chaisson RE. Incidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. The Zidovudine Epidemiology Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:1223–1227.

Article2. Jacobson MA, Stanley H, Holtzer C, Margolis TP, Cunningham ET. Natural history and outcome of new AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis diagnosed in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 30:231–233.

Article3. Le Moing V, Chene G, Carrieri MP, Alioum A, Brun-Vezinet F, Piroth L, et al. Predictors of virological rebound in HIV-1-infected patients initiating a protease inhibitor-containing regimen. Aids. 2002; 16:21–29.

Article4. Hodge WG, Boivin JF, Shapiro SH, Lalonde RG, Shah KC, Murphy BD, et al. Clinical risk factors for cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:1326–1333.

Article5. Studies of ocular complications of AIDS Foscarnet-Ganciclovir Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Trial: 1. Rationale, design, and methods. AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG). Control Clin Trials. 1992; 13:22–39.6. Jabs DA, Van Natta ML, Thorne JE, Weinberg DV, Meredith TA, Kuppermann BD, et al. Course of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: 2. Second eye involvement and retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:2232–2239.

Article7. Kwun YK, Chae JB, Ham DI. Cinical manifestations and prognosis of cytomegalovirus retinitis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2010; 51:203–209.

Article8. Lalezari JP, Friedberg DN, Bissett J, Giordano MF, Hardy WD, Drew WL, et al. High dose oral ganciclovir treatment for cytomegalovirus retinitis. J Clin Virol. 2002; 24:67–77.

Article9. Segarra-Newnham M, Salazar MI. Valganciclovir: a new oral alternative for cytomegalovirus retinitis in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals. Pharmacotherapy. 2002; 22:1124–1128.

Article10. Binder MI, Chua J, Kaiser PK, Procop GW, Isada CM. Endogenous endophthalmitis: an 18-year review of culture-positive cases at a tertiary care center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003; 82:97–105.11. Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003; 48:403–423.

Article12. Jackson TL, Paraskevopoulos T, Georgalas I. Systematic review of 342 cases of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014; 59:627–635.

Article13. Lee S, Um T, Joe SG, Hwang JU, Kim JG, Yoon YH, et al. Changes in the clinical features and prognostic factors of endogenous endophthalmitis: fifteen years of clinical experience in Korea. Retina. 2012; 32:977–984.

Article14. Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, D'Amico DJ, Baker AS. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101:832–838.15. Smith SR, Kroll AJ, Lou PL, Ryan EA. Endogenous bacterial and fungal endophthalmitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007; 47:173–183.

Article16. Schiedler V, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Davis JL, Benz MS, Miller D. Culture-proven endogenous endophthalmitis: clinical features and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004; 137:725–731.

Article17. Kim DY, Moon HI, Joe SG, Kim JG, Yoon YH, Lee JY. Recent Clinical Manifestation and Prognosis of Fungal Endophthalmitis: a 7-year experience at a tertiary referral center in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:960–964.

Article18. Krishna R, Amuh D, Lowder CY, Gordon SM, Adal KA, Hall G. Should all patients with candidaemia have an ophthalmic examination to rule out ocular candidiasis? Eye (Lond). 2000; 14(Pt 1):30–34.

Article19. Anand A, Madhavan H, Neelam V, Lily T. Use of polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:326–330.

Article20. Schwartz SG, Davis JL, Flynn HW. Endogenous Endophthalmitis. In : Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 5th ed. 2013.21. Riddell Jt, Comer GM, Kauffman CA. Treatment of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: focus on new antifungal agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52:648–653.

Article22. Breit SM, Hariprasad SM, Mieler WF, Shah GK, Mills MD, Grand MG. Management of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis with voriconazole and caspofungin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005; 139:135–140.

Article23. Subauste CS, Ajzenberg D, Kijlstra A. Review of the series "Disease of the year 2011: toxoplasmosis" pathophysiology of toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011; 19:297–306.

Article24. Lim SJ, Lee SE, Kim SH, Hong SH, You YS, Kwon OW, et al. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Toxocara canis among patients with uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015; 23:111–117.

Article25. Lim H, Lee SE, Jung BK, Kim MK, Lee MY, Nam HW, et al. Serologic survey of toxoplasmosis in Seoul and Jeju-do, and a brief review of its seroprevalence in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2012; 50:287–293.

Article26. Park YH, Nam HW. Clinical features and treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. Korean J Parasitol. 2013; 51:393–399.

Article27. Maenz M, Schluter D, Liesenfeld O, Schares G, Gross U, Pleyer U. Ocular toxoplasmosis past, present and new aspects of an old disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014; 39:77–106.

Article28. Park YH, Han JH, Nam HW. Clinical features of ocular toxoplasmosis in Korean patients. Korean J Parasitol. 2011; 49:167–171.

Article29. Elbez-Rubinstein A, Ajzenberg D, Darde ML, Cohen R, Dumetre A, Yera H, et al. Congenital toxoplasmosis and reinfection during pregnancy: case report, strain characterization, experimental model of reinfection, and review. J Infect Dis. 2009; 199:280–285.

Article30. Bosch-Driessen LE, Berendschot TT, Ongkosuwito JV, Rothova A. Ocular toxoplasmosis: clinical features and prognosis of 154 patients. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:869–878.31. Eckert GU, Melamed J, Menegaz B. Optic nerve changes in ocular toxoplasmosis. Eye (Lond). 2007; 21:746–751.

Article32. Montoya JG, Parmley S, Liesenfeld O, Jaffe GJ, Remington JS. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:1554–1563.

Article33. Marcolino PT, Silva DA, Leser PG, Camargo ME, Mineo JR. Molecular markers in acute and chronic phases of human toxoplasmosis: determination of immunoglobulin G avidity by Western blotting. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000; 7:384–389.

Article34. Belfort R, Silveira C, Muccioli C. Ocular toxoplasmosis. In : Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 5th ed. 2013.35. Soheilian M, Sadoughi MM, Ghajarnia M, Dehghan MH, Yazdani S, Behboudi H, et al. Prospective randomized trial of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole versus pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine in the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112:1876–1882.

Article36. Chang JH, Wakefield D. Uveitis: a global perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2002; 10:263–279.

Article37. Stewart JM, Cubillan LD, Cunningham ET, Jr . Prevalence, clinical features, and causes of vision loss among patients with ocular toxocariasis. Retina. 2005; 25:1005–1013.

Article38. Ament CS, Young LH. Ocular manifestations of helminthic infections: onchocersiasis, cysticercosis, toxocariasis, and diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006; 46:1–10.

Article39. Yokoi K, Goto H, Sakai J, Usui M. Clinical features of ocular toxocariasis in Japan. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003; 11:269–275.

Article40. Schneier AJ, Durand ML. Ocular toxocariasis: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2011; 51:135–144.41. Novak KD, Williams SM, Kokot I, Schultze RL. Nd:YAG photodestruction of a presumed corneal Toxocara canis larva. Cornea. 2010; 29:703–705.

Article42. Lyall DA, Hutchison BM, Gaskell A, Varikkara M. Intravitreal Ranibizumab in the treatment of choroidal neovascularisation secondary to ocular toxocariasis in a 13-year-old boy. Eye (Lond). 2010; 24:1730–1731.

Article43. Hook EW 3rd, Peeling RW. Syphilis control--a continuing challenge. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351:122–124.44. Fonollosa A, Giralt J, Pelegrin L, Sanchez-Dalmau B, Segura A, Garcia-Arumi J, et al. Ocular syphilis--back again: understanding recent increases in the incidence of ocular syphilitic disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009; 17:207–212.

Article45. Kwak HD, Kim HW, Lee JE, Lee JE, Lee SJ, Yun IH. Clinical manifestations of syphilitic uveitis in the Korean population. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2014; 55:555–562.

Article46. Pichi F, Ciardella AP, Cunningham ET Jr., Morara M, Veronese C, Jumper JM, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in patients with acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2014; 34:373–384.

Article47. Davis JL. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014; 25:513–518.

Article48. Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59:1–110.49. Julie H, aNAR T. Spirochetal Infections. In : Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 5th ed. 2013.50. Savaris RF, Abeche AM. Azithromycin versus penicillin for early syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:203–205. author reply -5

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Ocular manifestations of systemic tuberculosis: Report of 3 cases

- A Case of Ossification in the Phthisis Bulbi

- Clinical Manifestation of Infectious Keratitis in Ocular Graft Versus Host Disease

- Decreasing systemic inflammation after TIPS: Still hope for the liver: Reply to correspondence on “Insertion of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt leads to sustained reversal of systemic inflammation in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis”