Yonsei Med J.

2015 Nov;56(6):1738-1741. 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.6.1738.

Successful Treatment of Infectious Scleritis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with Autologous Perichondrium Graft of Conchal Cartilage

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Gyeongsang National University College of Medicine, Jinju, Korea. maya12kim@naver.com

- 2Department of Otolaryngology, Gyeongsang National University College of Medicine, Jinju, Korea.

- 3Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Korea.

- KMID: 2345908

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.6.1738

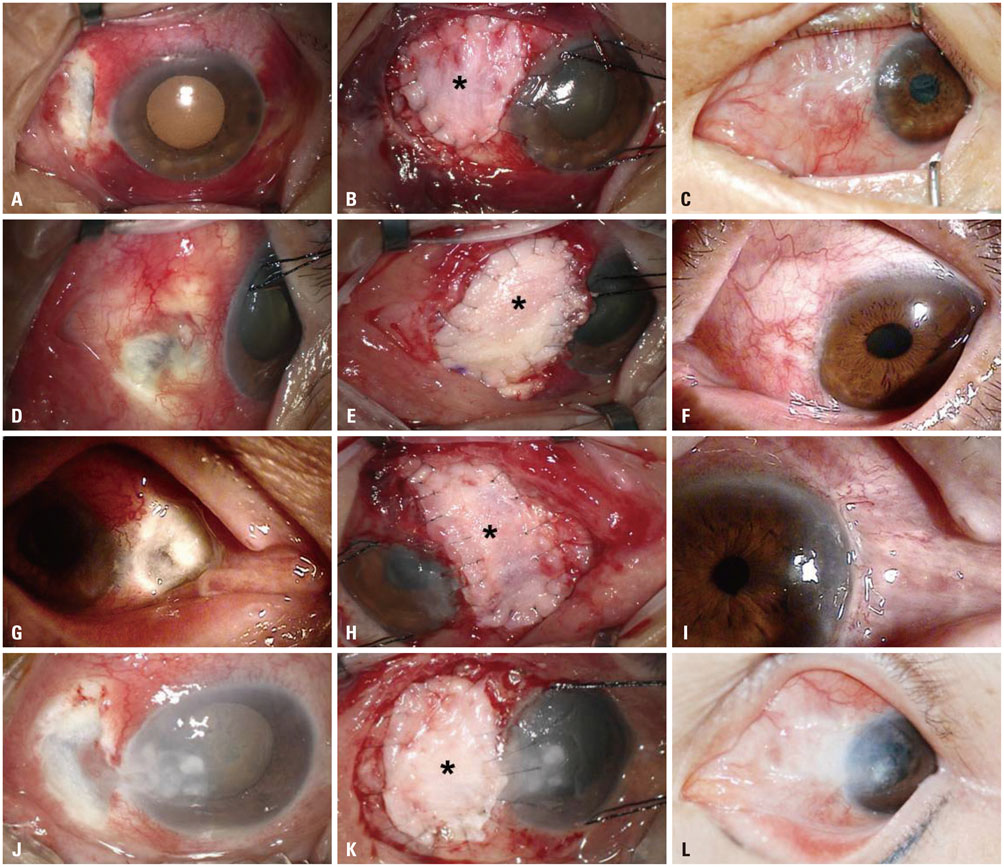

Abstract

- Infectious scleritis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a well-known vision-threatening disease. In particular, scleral trauma following pterygium surgery may increase the risk of sclera inflammation. Surgical debridement and repair is necessary in patients who do not respond to medical treatments, such as topical and intravenous antibiotics. We reports herein the effectiveness of an autologous perichondrium conchal cartilage graft for infectious scleritis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This procedure was performed on four eyes of four patients with infectious scleritis who had previously undergone pterygium surgery at Gyeongsang National University Hospital (GNUH), Jinju, Korea from December 2011 to May 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was identified in cultures of necrotic scleral lesion before surgery. The conchal cartilage perichondrium graft was transplanted, and a conjunctival flap was created on the scleral lesion. The autologous perichondrium conchal cartilage graft was successful and visual outcome was stable in all patients, with no reports of graft failure or infection recurrence. In conclusion, autologous perichondrium conchal cartilage graft may be effective in surgical management of Pseudomonal infectious scleritis when non-surgical medical treatment is ineffective. Further studies in larger, diverse populations are warranted to establish the effectiveness of the procedure.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Anti-Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use

Autografts

Cartilage/surgery

Communicable Diseases

Debridement

Eye Infections, Bacterial/etiology/*therapy

Female

Humans

Ophthalmologic Surgical Procedures

Postoperative Complications

Pseudomonas Infections/microbiology/*therapy

Pseudomonas aeruginosa/*isolation & purification

Pterygium/surgery

Republic of Korea

Sclera/*surgery/transplantation

Scleritis/microbiology/*therapy

Surgical Wound Infection/microbiology/*therapy

Transplantation, Autologous

Treatment Outcome

Anti-Bacterial Agents

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shang Y, Han S, Li J, Ren Q, Song F, Chen H. The clinical feature of Behçet's disease in Northeastern China. Yonsei Med J. 2009; 50:630–636.

Article2. Jain V, Garg P, Sharma S. Microbial scleritis-experience from a developing country. Eye (Lond). 2009; 23:255–261.

Article3. Ho YF, Yeh LK, Tan HY, Chen HC, Chen YF, Lin HC, et al. Infectious scleritis in Taiwan-a 10-year review in a tertiary-care hospital. Cornea. 2014; 33:838–843.

Article4. Hodson KL, Galor A, Karp CL, Davis JL, Albini TA, Perez VL, et al. Epidemiology and visual outcomes in patients with infectious scleritis. Cornea. 2013; 32:466–472.

Article5. Lin CP, Shih MH, Tsai MC. Clinical experiences of infectious scleral ulceration: a complication of pterygium operation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997; 81:980–983.

Article6. Parodi PC, Calligaris F, De Biasio F, De Maglio G, Miani F, Zeppieri M. Lower lid reconstruction utilizing auricular conchal chondralperichondral tissue in patients with neoplastic lesions. Biomed Res Int. 2013; 2013:837536.

Article7. Watson P, Romano A. The impact of new methods of investigation and treatment on the understanding of the pathology of scleral inflammation. Eye (Lond). 2014; 28:915–930.

Article8. Watson P, Hazleman BL, McCluskey P, Favesio CE. The sclera and systemic disorders. 3rd ed. London: JP Medical Ltd.;2012.9. Paula JS, Simão ML, Rocha EM, Romão E, Velasco Cruz AA. Atypical pneumococcal scleritis after pterygium excision: case report and literature review. Cornea. 2006; 25:115–117.10. Nguyen QD, Foster CS. Scleral patch graft in the management of necrotizing scleritis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1999; 39:109–131.

Article11. Togo T, Utani A, Naitoh M, Ohta M, Tsuji Y, Morikawa N, et al. Identification of cartilage progenitor cells in the adult ear perichondrium: utilization for cartilage reconstruction. Lab Invest. 2006; 86:445–457.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Efficacy of Autologous Tragal Perichondrium Graft after Proper Antifungal Treatment in Fungal Necrotizing Scleritis

- Ocular Reconstruction Using Autologous Tragal Perichondrium for a Refractory Necrotizing Scleral Perforation: A Case Report

- 4 Cases of Pseudomonas Scleritis after Pterygium Excision

- Volume and Weight Changes of Autologous Costal Cartilage Grafts with and without Perichondrium in Human

- Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Infectious Scleritis