J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2012 Jun;53(6):749-760.

Effects of Temporary Amniotic Membrane Patch after Surgical Excision of Primary Pterygium

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. sbummlee@med.yu.ac.kr

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the clinical results, recurrence rates, and recurrence-related risk factors of temporary amniotic membrane patch (TAMP) after excision of primary pterygium.

METHODS

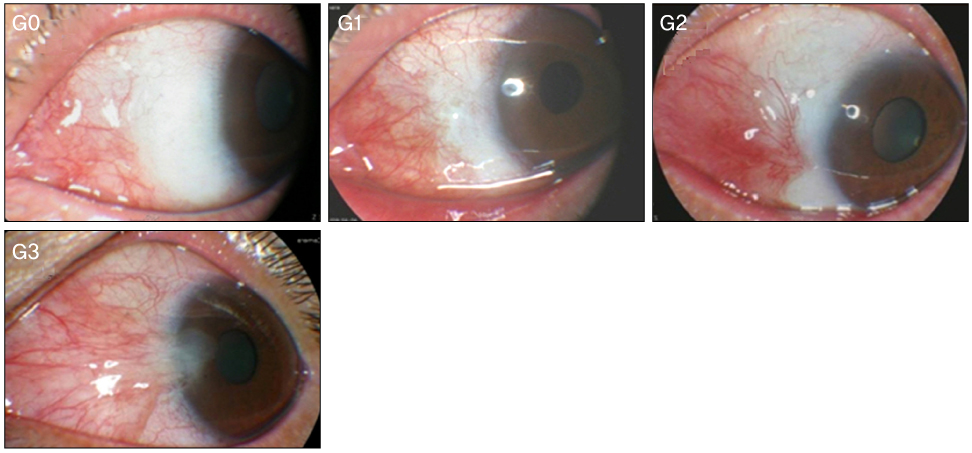

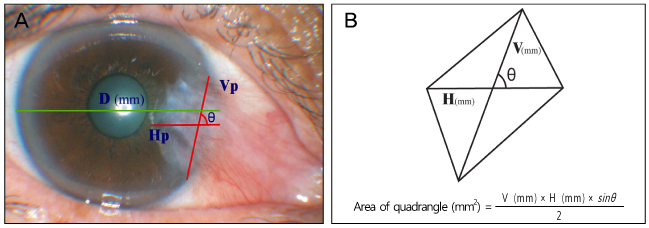

Recurrence grade was evaluated for 73 eyes with a mean follow-up of 15.5 months (range 9 to 56 months). Surgical results were classified into surgical success (G0/G1), conjunctival recurrence (G2), and corneal recurrence (G3). Recurrence rates were analyzed based on gender, age, Tan's preoperative grading system, horizontal and vertical length of the preoperative pterygium, the corneal involvement size of the preoperative pterygium, planned or unplanned removal of amniotic membrane, and epithelial healing time. Using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, the cumulative proportion of integrated G0/G1 was evaluated.

RESULTS

In the postoperative grading, 58 (79.5%) and 9 (12.3%) eyes were graded as clinically recurrence-free G0 and G1, respectively; 4 (5.5%) and 2 (2.7%) eyes were graded as clinically recurrence-occurred G2 and G3, respectively. The cumulative proportion of integrated recurrence-free G0/G1 at 24 months after surgery was 0.83 +/- 0.08. T3 of Tan's preoperative grading system was identified as the only risk factor for recurrence above G1 through multivariate logistic regression analysis (p = 0.02).

CONCLUSIONS

The recurrence rate of the present TAMP study showed better results in comparison with 9.1 to 56.1% of recurrence rates in other studies. The TAMP has advantages of surgical procedure with ease, low complications, and low recurrence rates. Therefore, after surgical excision of primary pterygium, the authors concluded the TAMP is highly recommended for good clinical outcomes and low recurrence rates.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Solomon A, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation after extensive removal of primary and recurrent pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2001. 108:449–460.2. Verma N, Garap JA, Maris R, Kerek A. Intraoperative use of mitomycin C in the treatment of recurrent pterygium. P N G Med J. 1998. 41:37–42.3. Tan DT, Chee SP, Dear KB, Lim AS. Effect of pterygium morphology on pterygium recurrence in a controlled trial comparing conjunctival autografting with bare sclera excision. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997. 115:1235–1240.4. Riordan-Eva P, Kielhorn I, Ficker LA, et al. Conjunctival autografting in the surgical management of pterygium. Eye (Lond). 1993. 7(Pt 5):634–638.5. Panda A, Das GK, Tuli SW, Kumar A. Randomized trial of intraoperative mitomycin C in surgery for pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998. 125:59–63.6. Chen PP, Ariyasu RG, Kaza V, et al. A randomized trial comparing mitomycin C and conjunctival autograft after excision of primary pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995. 120:151–160.7. Kim JC, Tseng SC. Transplantation of preserved human amniotic membrane for surface reconstruction in severely damaged rabbit corneas. Cornea. 1995. 14:473–484.8. Ye J, Kook KH, Yao K. Temporary amniotic membrane patch for the treatment of primary pterygium: mechanisms of reducing the recurrence rate. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006. 244:583–588.9. Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SC. Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary closure for pterygium excision. Ophthalmology. 1997. 104:974–985.10. Luanratanakorn P, Ratanapakorn T, Suwan-Apichon O, Chuck RS. Randomised controlled study of conjunctival autograft versus amniotic membrane graft in pterygium excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006. 90:1476–1480.11. Küçükerdönmez C, Akova YA, Altinörs DD. Comparison of conjunctival autograft with amniotic membrane transplantation for pterygium surgery: surgical and cosmetic outcome. Cornea. 2007. 26:407–413.12. Park WC. New strategy of ocular surface disease - Ocular surface reconstruction using amniotic membrane and limbal stem cell transplantation. J Korean Med Assoc. 2005. 48:628–633.13. Kwak DY, Lee JK, Park DJ. Pterygium surgery: Wide excision with amniotic membrane transplantation using fibrin glue. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008. 49:213–221.14. Kobayashi A, Shirao Y, Yoshita T, et al. Temporary amniotic membrane patching for acute chemical burns. Eye (Lond). 2003. 17:149–158.15. Kheirkhah A, Johnson DA, Paranjpe DR, et al. Temporary sutureless amniotic membrane patch for acute alkaline burns. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008. 126:1059–1066.16. Threlfall TJ, English DR. Sun exposure and pterygium of the eye: a dose-response curve. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999. 128:280–287.17. Dushku N, John MK, Schultz GS, Reid TW. Pterygia pathogenesis: corneal invasion by matrix metalloproteinase expressing altered limbal epithelial basal cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001. 119:695–706.18. Weinstein O, Rosenthal G, Zirkin H, et al. Overexpression of p53 tumor suppressor gene in pterygia. Eye (Lond). 2002. 16:619–621.19. Tan DT, Lim AS, Goh HS, Smith DR. Abnormal expression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in the conjunctiva of patients with pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997. 123:404–405.20. Dushku N, Reid TW. P53 expression in altered limbal basal cells of pingueculae, pterygia, and limbal tumors. Curr Eye Res. 1997. 16:1179–1192.21. Shimmura S, Ishioka M, Hanada K, et al. Telomerase activity and p53 expression in pterygia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000. 41:1364–1369.22. Detorakis ET, Spandidos DA. Pathogenetic mechanisms and treatment options for ophthalmic pterygium: trends and perspectives (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2009. 23:439–447.23. Detorakis ET, Zaravinos A, Spandidos DA. Growth factor expression in ophthalmic pterygia and normal conjunctiva. Int J Mol Med. 2010. 25:513–516.24. Lee SB, Li DQ, Tan DT, et al. Suppression of TGF-beta signaling in both normal conjunctival fibroblasts and pterygial body fibroblasts by amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res. 2000. 20:325–334.25. Ti SE, Tseng SC. Management of primary and recurrent pterygium using amniotic membrane transplantation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002. 13:204–212.26. Ma DH, See LC, Hwang YS, Wang SF. Comparison of amniotic membrane graft alone or combined with intraoperative mitomycin C to prevent recurrence after excision of recurrent pterygia. Cornea. 2005. 24:141–150.27. Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011. 118:908–914.28. Hayashi H, Sakai J, Matsuura H, Fujimoto W. Cyclophosphamide and amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of ocular disease in a case of antiepiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009. 34:e477–e479.29. Zhong Y, Zhai Z, Zhou Y, et al. [Effect of amniotic membrane on expressions of TGF-beta 1, collagens I, III and fibronectin in rabbit corneal healing after photorefractive keratectomy]. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2000. 16:239–242.30. Shimazaki J, Kosaka K, Shimmura S, Tsubota K. Amniotic membrane transplantation with conjunctival autograft for recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2003. 110:119–124.31. Al Fayez MF. Limbal versus conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2002. 109:1752–1755.32. Kwak DY, Bae MC, Lee JK, Park DJ. Wide excision with conjunctivo-limbal autograft. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008. 49:205–212.33. Mahar PS, Nwokora GE. Role of mitomycin C in pterygium surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993. 77:433–435.34. Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sekiyama E, et al. Novel clinical application of sterilized, freeze-dried amniotic membrane to treat patients with pterygium. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006. 84:401–405.35. Boudreau N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Suppression of apoptosis by basement membrane requires three-dimensional tissue organization and withdrawal from the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996. 93:3509–3513.36. Mutlu FM, Sobaci G, Tatar T, Yildirim E. A comparative study of recurrent pterygium surgery: limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation versus mitomycin C with conjunctival flap. Ophthalmology. 1999. 106:817–821.37. Ti SE, Chee SP, Dear KB, Tan DT. Analysis of variation in success rates in conjunctival autografting for primary and recurrent pterygium. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000. 84:385–389.38. Kenyon KR, Wagoner MD, Hettinger ME. Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 1985. 92:1461–1470.39. Fernandes M, Sangwan VS, Bansal AK, et al. Outcome of pterygium surgery: analysis over 14 years. Eye (Lond). 2005. 19:1182–1190.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of Permanent Amniotic Membrane Transplantation and Temporary Amniotic Membrane Patch after Primary Pterygium Excision

- The Effect of Amniotic Membrane Transplantation for Pterygium Excision

- Ocular Surface Reconstruction with Amniotic Membrane Transplantation in Pterygium

- Progenitor Cells in Healing after Pterygium Excision

- Surgical Outcome of Primary Pterygium Excision with Conjunctival Autograft