J Korean Soc Spine Surg.

2016 Jun;23(2):114-120. 10.4184/jkss.2016.23.2.114.

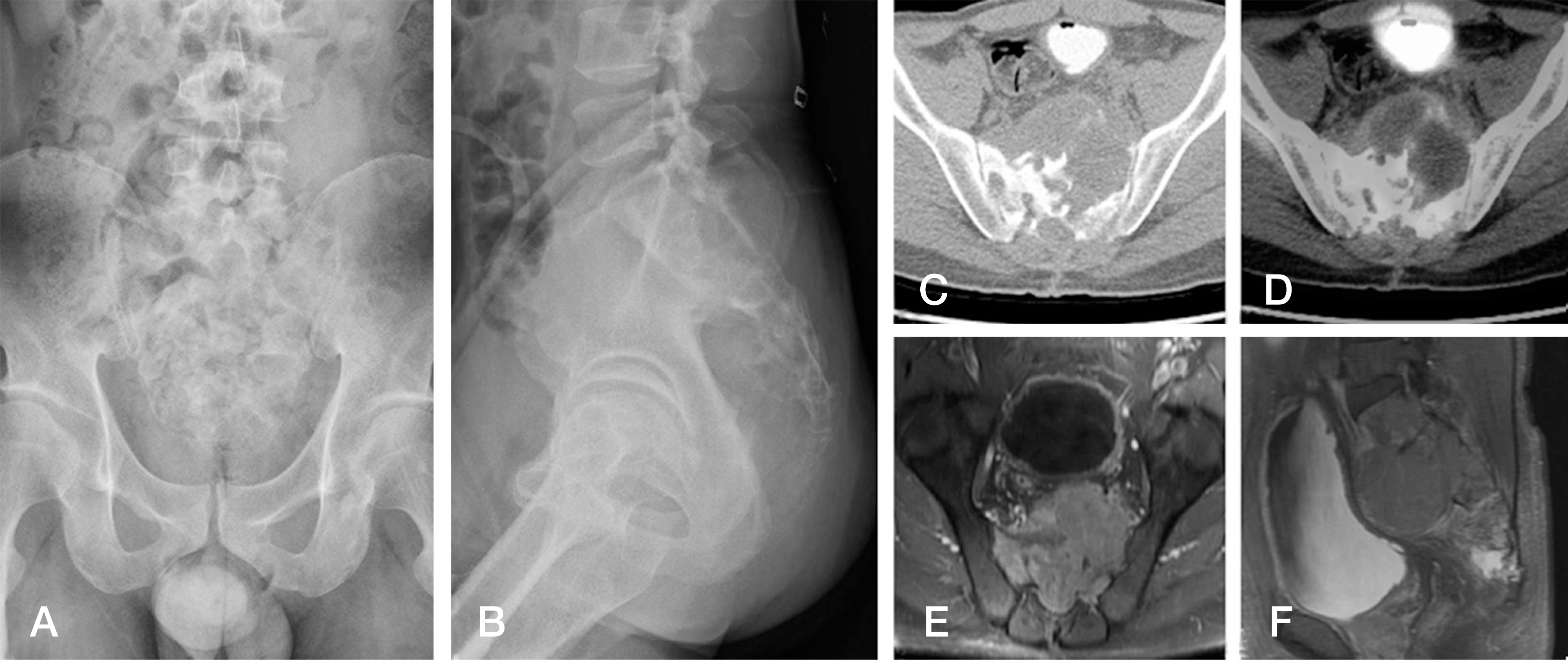

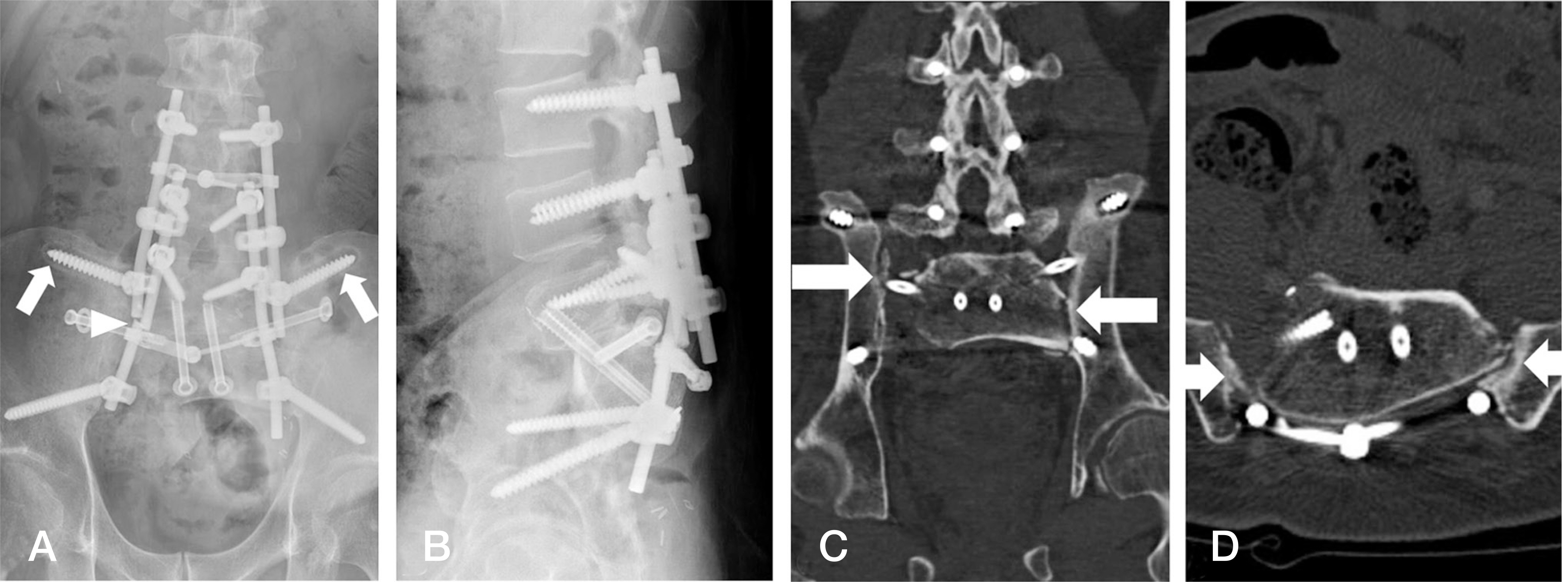

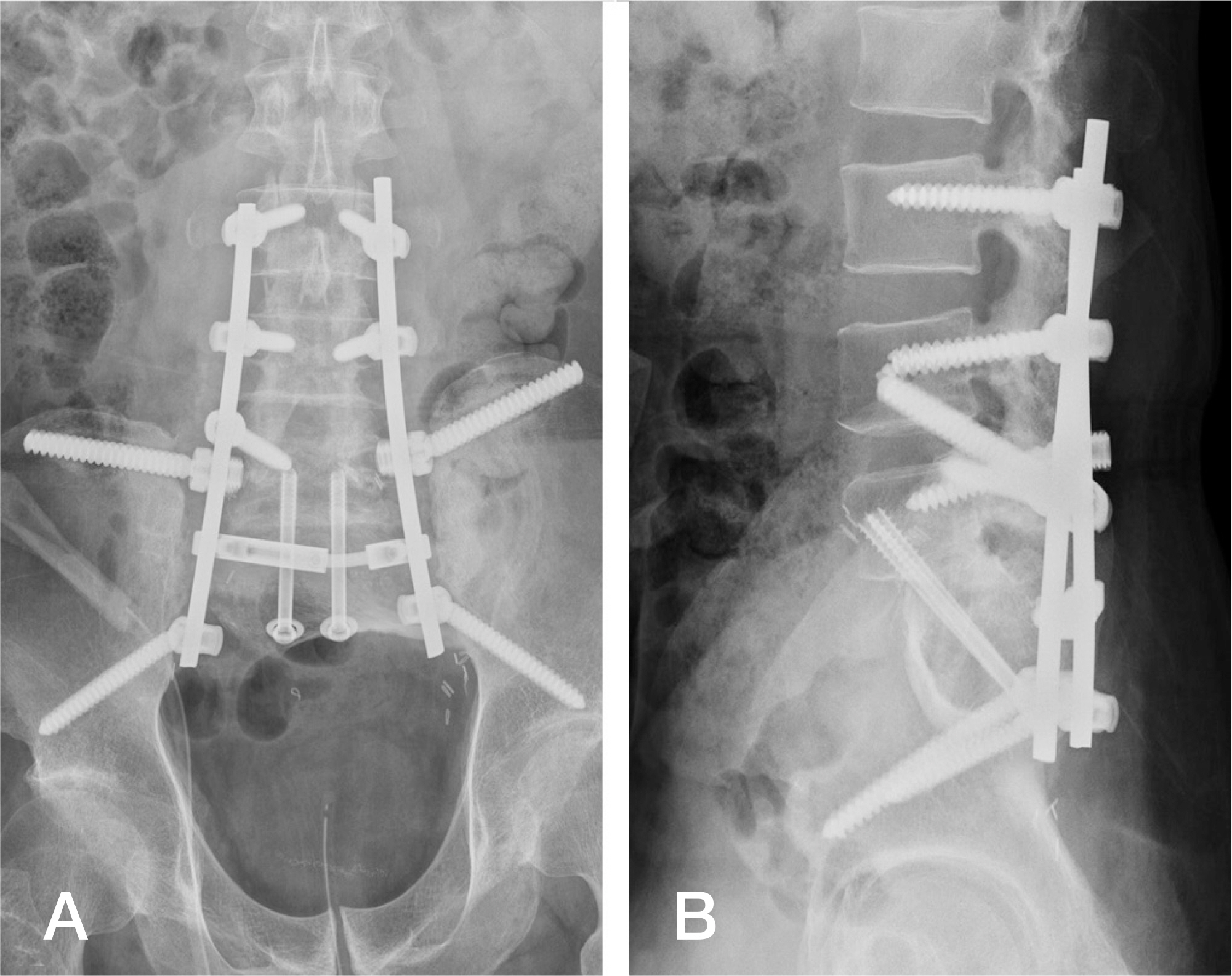

Spinopelvic Reconstruction with Femoral Allograft and Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous Flap after Total Sacrectomy in Recurrent Sacral Chordoma: A Case Report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. bschang@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2328005

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4184/jkss.2016.23.2.114

Abstract

- STUDY DESIGN: Case report.

OBJECTIVES

To report a case of recurrent sacral chordoma treated with total sacrectomy and spinopelvic reconstruction. SUMMARY OF LITERATURE REVIEW: Sacral chordoma is a musculoskeletal tumor reported to have a low incidence. Surgical treatment is considered difficult due to the complicated sacropelvic structure, so the prognosis for patients with sacral chordoma has been considered poor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We report a surgical technique and outcomes from spinopelvic reconstruction with femoral allograft and vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap after total sacrectomy.

RESULTS

We report no tumor recurrence at 43 months postoperatively.

CONCLUSIONS

Spinopelvic reconstruction with thorough surgical planning after total sacrectomy was found to be a safe and effective treatment method.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bederman SS, Shah KN, Hassan JM, et al. Surgical techniques for spinopelvic reconstruction following total sacrectomy: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2014; 23:305–19.

Article2. Todd LTJ, Yaszemski MJ, Currier BL, et al. Bowel and bladder function after major sacral resection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002; 397:36–9.

Article3. Zhang HY, Thongtrangan I, Balabhadra RS, et al. Surgical techniques for total sacrectomy and spinopelvic reconstruction. Neurosurg Focus. 2003; 15:E5.

Article4. Bohinski RJ, Mendel E, Rhines LD. Novel use of a thread-wire saw for high sacral amputation. Technical note and description of operative technique. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005; 3:71–8.5. Shikata J, Yamamuro T, Kotoura Y, et al. Total sacrectomy and reconstruction for primary tumors. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988; 70:122–5.

Article6. Blatter G, Halter Ward EG, Ruflin G, et al. The problem of stabilization after sacrectomy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1994; 114:40–2.

Article7. Wuisman P, Lieshout O, van Dijk M, et al. Reconstruction after total en bloc sacrectomy for osteosarcoma using a custom-made prosthesis: a technical note. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26:431–9.8. Gokaslan ZL, Romsdahl MM, Kroll SS, et al. Total sacrectomy and Galveston L-rod reconstruction for malignant neoplasms. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1997; 87:781–7.9. Touny A, Othman H, Maamoon S, et al. Perineal reconstruction using pedicled vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (VRAM). J Surg Oncol. 2014; 110:752–7.

Article10. Guo Y, Palmer JL, Shen L, et al. Bowel and bladder con-tinence, wound healing, and functional outcomes in patients who underwent sacrectomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005; 3:106–10.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Breast Reconstruction with Free Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous Flap Complicated by Deep Vein Thrombosis-associated Pulmonary Thrombo-embolism

- Rectus Abdominis Free Flap Reconstruction for Orbital-Maxillary Defect in Advanced Maxillary Sinus Cancer

- Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous-Pedicled Island Flap for Covering Defect of the Suprapubic Area: A Case Report

- The Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous Flap for the Immediate Reconstruction of Partial Vaginal Defects Following the Extended Abdominoperineal Resection of Recurrent Rectal Cancer

- Reconstruction of Midfacial Defect Using Various Free Flap