Tuberc Respir Dis.

2011 Jan;70(1):51-57.

Utility of Serum Procalcitonin for Diagnosis of Sepsis and Evaluation of Severity

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. sbhong@amc.seoul.kr

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Early recognition and treatment of sepsis would improve patients' outcome. But it is difficult to distinguish between sepsis and non-infectious conditions in the acute phase of clinical deterioration. We studied serum level of procalcitonin (PCT) as a method to diagnose and to evaluate sepsis.

METHODS

Between 1 March 2009 and 30 September 2009, 178 patients had their serum PCT tested during their clinical deterioration in the medical intensive care unit. These laboratories were evaluated, on a retrospective basis. We classified their clinical status as non-infection, local infection, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. Then, we compared their clinical status with level of PCT.

RESULTS

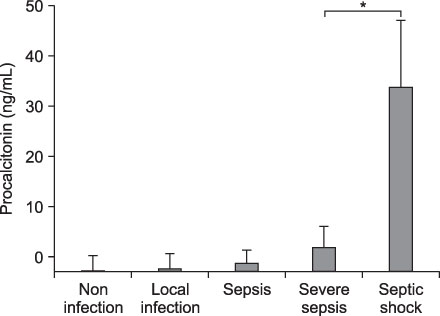

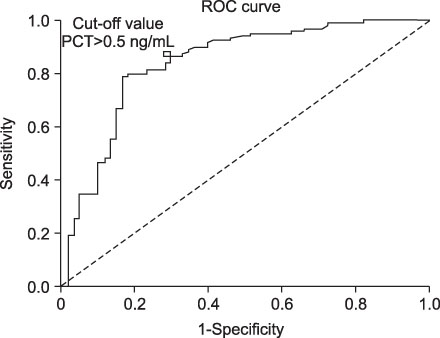

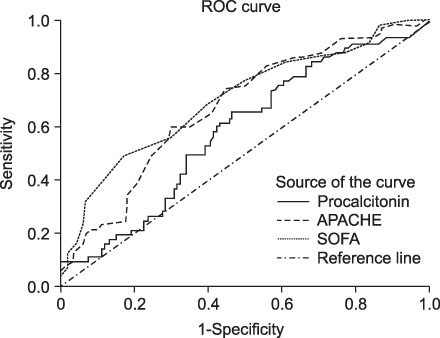

The number of clinical status is as follows: 18 non-infection, 33 local infection, 39 sepsis, 26 severe sepsis, and 62 septic shock patients. PCT level of non-septic group (non-infection and local infection) and septic group (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock) was 0.36+/-0.57 ng/mL and 18.09+/-36.53 ng/mL (p<0.001), respectively. Area under the curve for diagnosis of sepsis using cut-off value of PCT >0.5 ng/mL was 0.841 (p<0.001). Level of PCT as clinical status was statistically different between severe sepsis and septic shock (*severe sepsis; 4.53+/-6.15 ng/mL, *septic shock 34.26+/-47.10 ng/mL, *p<0.001).

CONCLUSION

Level of PCT at clinical deterioration showed diagnostic power for septic condition. The level of PCT was statistically different between severe sepsis and septic shock.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995. 273:117–123.2. Hong SK, Hong SB, Lim CM, Koh Y. The characteristics and prognostic factors of severe sepsis in patients who were admitted to a medical intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2009. 24:28–32.3. Vincent JL, Bihari D. Sepsis, severe sepsis or sepsis syndrome: need for clarification. Intensive Care Med. 1992. 18:255–257.4. Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet. 1993. 341:515–518.5. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992. 20:864–874.6. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985. 13:818–829.7. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996. 22:707–710.8. Becker KL, Nylén ES, White JC, Müller B, Snider RH Jr. Clinical review 167: Procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene family of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sepsis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precursors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89:1512–1525.9. Meisner M, Müller V, Khakpour Z, Toegel E, Redl H. Induction of procalcitonin and proinflammatory cytokines in an anhepatic baboon endotoxin shock model. Shock. 2003. 19:187–190.10. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J. 2007. 30:556–573.11. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Procalcitonin in bacterial infections--hype, hope, more or less? Swiss Med Wkly. 2005. 135:451–460.12. Herzum I, Renz H. Inflammatory markers in SIRS, sepsis and septic shock. Curr Med Chem. 2008. 15:581–587.13. Rau BM, Kemppainen EA, Gumbs AA, Büchler MW, Wegscheider K, Bassi C, et al. Early assessment of pancreatic infections and overall prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis by procalcitonin (PCT): a prospective international multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2007. 245:745–754.14. Whang KT, Steinwald PM, White JC, Nylen ES, Snider RH, Simon GL, et al. Serum calcitonin precursors in sepsis and systemic inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998. 83:3296–3301.15. Nakamura A, Wada H, Ikejiri M, Hatada T, Sakurai H, Matsushima Y, et al. Efficacy of procalcitonin in the early diagnosis of bacterial infections in a critical care unit. Shock. 2009. 31:586–591.16. Sandri MT, Passerini R, Leon ME, Peccatori FA, Zorzino L, Salvatici M, et al. Procalcitonin as a useful marker of infection in hemato-oncological patients with fever. Anticancer Res. 2008. 28:3061–3065.17. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, Gencay MM, Huber PR, Tamm M, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004. 363:600–607.18. Stocker M, Fontana M, El Helou S, Wegscheider K, Berger TM. Use of procalcitonin-guided decision-making to shorten antibiotic therapy in suspected neonatal early-onset sepsis: prospective randomized intervention trial. Neonatology. 2010. 97:165–174.19. Meng FS, Su L, Tang YQ, Wen Q, Liu YS, Liu ZF. Serum procalcitonin at the time of admission to the ICU as a predictor of short-term mortality. Clin Biochem. 2009. 42:1025–1031.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Utility of Serum Procalcitonin Levels in the Management of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome in the Emergency Department

- Clinical Utility of Procalcitonin on Antibiotic Stewardship: A Narrative Review

- Clinical utility of procalcitonin in severe odontogenic maxillofacial infection

- Update on Procalcitonin Measurements

- The value of presepsin, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein in sepsis associated organ failure in the emergency department: a retrospective analysis according to the Sepsis-3 definition