Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr.

2015 Jun;18(2):85-93. 10.5223/pghn.2015.18.2.85.

Differences in Clinical and Laboratory Findings between Group D and Non-Group D Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Gastroenteritis in Children

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea. seozee@gnu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Biochemistry, Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea.

- 3Department of Otolaryngology, Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea.

- KMID: 2315554

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2015.18.2.85

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the differences in clinical features and laboratory findings between group D and non-group D non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) gastroenteritis in children.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of children diagnosed with NTS confirmed by culture study was performed. The clinical features and laboratory findings of group D and non-group D NTS were compared.

RESULTS

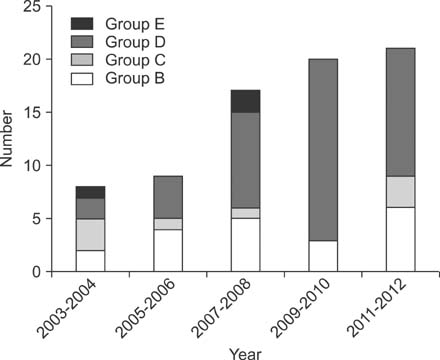

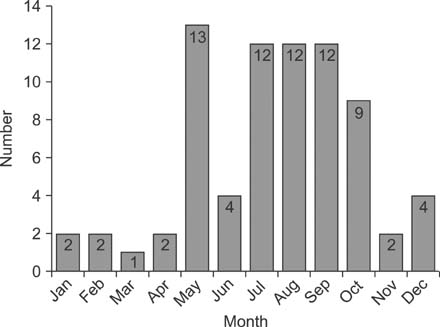

From 2003 to 2012, 75 cases were diagnosed as NTS at our center. The number of group D and non-group D patients was 45 and 30, respectively. The mean age was higher in group D than in non-group D patients (5.1 years vs. 3.4 years, p=0.038). Headaches were more frequently observed (p=0.046) and hematochezia was less frequently observed (p=0.017) in group D than in non-group D NTS gastroenteritis patients. A positive Widal test result was observed in 53.3% of group D and 6.7% of non-group D NTS cases (O-titer, p=0.030; H-titer, p=0.039). There were no differences in white blood cell counts, level of C-reactive protein and rate of antimicrobial resistance between group D and non-group D cases.

CONCLUSION

The more severe clinical features such as headache, fever, and higher Widal titers were found to be indicative of group D NTS gastroenteritis. Additionally, group D NTS gastroenteritis was more commonly found in older patients. Therefore, old age, fever, headache, and a positive Widal test are more indicative of group D NTS than non-group D NTS gastroenteritis. Pathophysiological mechanisms may differ across serologic groups.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Experience of Campylobacter gastroenteritis in Korean children: Single-center study

Seung Hyeon Seo, Yeoun Joo Lee, Sang Wook Mun, Jae Hong Park

Kosin Med J. 2018;33(2):150-158. doi: 10.7180/kmj.2018.33.2.150.

Reference

-

1. Hohmann EL. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 32:263–269.

Article2. Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O'Brien SJ, et al. International Collaboration on Enteric Disease 'Burden of Illness' Studies. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010; 50:882–889.

Article3. Chen HM, Wang Y, Su LH, Chiu CH. Nontyphoid salmonella infection: microbiology, clinical features, and antimicrobial therapy. Pediatr Neonatol. 2013; 54:147–152.

Article4. Su LH, Chiu CH, Chu C, Ou JT. Antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoid Salmonella serotypes: a global challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:546–551.

Article5. Bäumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Ficht TA, Adams LG. Evolution of host adaptation in Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun. 1998; 66:4579–4587.6. Seo Y, Ha YE, Sung KI, Kang CI, Peck KR, Song JH, et al. A case of an infected pseudoaneurysm with complications due to a non-typhoidal Salmonella species. Korean J Med. 2012; 83:272–276.

Article7. Lee JH, Huh JG, Nah JC, Kim ES, Lee HK, Shin BM, et al. Enteric fever with bowel perforation caused by nontyphoidal group D Salmonella. Infect Chemother. 2004; 36:251–254.8. Cho JY, Seo JH, Yeom JS, Park JS, Park CH, Woo HO, et al. Diffuse colonic ulcer caused by Salmonella enteritidis in a 32-month-old female. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2012; 15:193–196.

Article9. Nah SY, Park JY, Lee HJ, Seo JK. Epidemiologic and clinical features of salmonellosis in children over 10 years (1986-1995). Korean J Infect Dis. 1999; 31:129–135.10. Noh SH, Yu KY, Kim JS, Hwang PH, Jo DS. Salmonellosis in children: analysis of 72 Salmonella-positive culture cases during the last 10 years. Korean J Pediatr. 2009; 52:791–797.

Article11. Park JH, Lee TJ. Clinical manifestations of salmonellosis in children during the last 12 years: a single institution experience. Korean J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2013; 20:1–8.

Article12. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence and characteristics of bacteria causing acute diarrhea in Korea, 2008. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2008. 1:p. 1–8.13. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence and characteristics of bacteria causing acute diarrhea in Korea, 2009. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2009. 1:p. 1–9.14. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence and characteristics of bacteria causing acute diarrhea in Korea, 2011. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2010. 1:p. 1–8.15. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence and characteristics of bacteria causing acute diarrhea in Korea, 2012. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2011. 1:p. 1–6.16. Olsen SJ, Bishop R, Brenner FW, Roels TH, Bean N, Tauxe RV, et al. The changing epidemiology of salmonella: trends in serotypes isolated from humans in the United States, 1987-1997. J Infect Dis. 2001; 183:753–761.

Article17. United States Department of Agriculture. Report to Congress 1998. FoodNet: an active surveillance system for bacterial foodborne diseases in the United States [Internet]. Washington DC: United States. Department of Agriculture;1998. cited 2008 Jun 2. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/ophs/rpcong98/rpcong98.htm.18. Jones TF, Ingram LA, Fullerton KE, Marcus R, Anderson BJ, McCarthy PV, et al. A case-control study of the epidemiology of sporadic Salmonella infection in infants. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:2380–2387.

Article19. Delarocque-Astagneau E, Bouillant C, Vaillant V, Bouvet P, Grimont PA, Desenclos JC. Risk factors for the occurrence of sporadic Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium infections in children in France: a national case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 31:488–492.

Article20. Kimura AC, Reddy V, Marcus R, Cieslak PR, Mohle-Boetani JC, Kassenborg HD, et al. Chicken consumption is a newly identified risk factor for sporadic salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis infections in the united states: a case-control study in Foodnet sites. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 38:Suppl 3. S244–S252.21. Younus M, Wilkins MJ, Davies HD, Rahbar MH, Funk J, Nguyen C, et al. Case-control study of disease determinants for non-typhoidal Salmonella infections among Michigan children. BMC Res Notes. 2010; 3:105.

Article22. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported food poisoning outbreak in 1989 epidemiological study. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;1990. 1:p. 3.23. Park HM, Lee DY. Prevalence and charateristics of Salmonella spp. in Korea, 2012. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2013. 6:p. 105–116.24. Chae SJ, Lee DY. Prevalence and charateristics of Salmonella spp. in Korea, 2013. Public Health Weekly Report. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014. 7:p. 385–390.25. Hammack T. Salmonella species. In : Lampel KA, editor. Bad bug book e handbook of foodborne pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins. 2nd ed. Washington DC: Food and Drug Administration;2012. p. 12–16.26. Peters RP, Zijlstra EE, Schijffelen MJ, Walsh AL, Joaki G, Kumwenda JJ, et al. A prospective study of bloodstream infections as cause of fever in Malawi: clinical predictors and implications for management. Trop Med Int Health. 2004; 9:928–934.

Article27. Graham SM, Walsh AL, Molyneux EM, Phiri AJ, Molyneux ME. Clinical presentation of non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteraemia in Malawian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000; 94:310–314.

Article28. Punpanich W, Netsawang S, Thippated C. Invasive salmonellosis in urban Thai children: a ten-year review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012; 31:e105–e110.29. Tsai KS, Yang YJ, Wang SM, Chiou CS, Liu CC. Change of serotype pattern of Group D non-typhoidal Salmonella isolated from pediatric patients in southern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007; 40:234–239.30. Kim SE, Kim TY, Park IK, Kang JO, Yeal T. Is the Widal test still useful? Korean J Clin Pathol. 1999; 19:215–221.31. Andualem G, Abebe T, Kebede N, Gebre-Selassie S, Mihret A, Alemayehu H. A comparative study of Widal test with blood culture in the diagnosis of typhoid fever in febrile patients. BMC Res Notes. 2014; 7:653.

Article32. Zulfiqar AB. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. In : Kliegman RM, editor. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders;2011. p. 948–958.33. Mattila L, Peltola H, Siitonen A, Kyrönseppä H, Simula I, Kataja M. Short-term treatment of traveler's diarrhea with norfloxacin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study during two seasons. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 17:779–782.

Article34. Dryden MS, Gabb RJ, Wright SK. Empirical treatment of severe acute community-acquired gastroenteritis with ciprofloxacin. Clin Infect Dis. 1996; 22:1019–1025.

Article35. Goodman LJ, Trenholme GM, Kaplan RL, Segreti J, Hines D, Petrak R, et al. Empiric antimicrobial therapy of domestically acquired acute diarrhea in urban adults. Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:541–546.

Article36. Tsai MH, Huang YC, Lin TY, Huang YL, Kuo CC, Chiu CH. Reappraisal of parenteral antimicrobial therapy for nontyphoidal Salmonella enteric infection in children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011; 17:300–305.

Article37. Helms M, Simonsen J, Molbak K. Quinolone resistance is associated with increased risk of invasive illness or death during infection with Salmonella serotype Typhimurium. J Infect Dis. 2004; 190:1652–1654.

Article38. Varma JK, Molbak K, Barrett TJ, Beebe JL, Jones TF, Rabatsky-Ehr T, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella is associated with excess bloodstream infections and hospitalizations. J Infect Dis. 2005; 191:554–561.

Article39. Su LH, Chiu CH, Chu C, Ou JT. Antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoid Salmonella serotypes: a global challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:546–551.

Article40. Singh S, Agarwal RK, Tiwari SC, Singh H. Antibiotic resistance pattern among the Salmonella isolated from human, animal and meat in India. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012; 44:665–674.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cervical Lymphadenitis Caused by Group D Non-typhoidal Salmonella Associated with Concomitant Lymphoma

- Acute myocarditis associated with non-typhoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis

- Non-typhoidal Salmonella Gastroenteritis in Childhood: Clinical Features and Antibiotics Resistance

- Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Salmonellosis in Children over 10 Years(1986-1995)

- The Serogroup and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella spp. Isolated from the Clinical Specimens During 6 years in a Tertiary University Hospital