Nutr Res Pract.

2014 Feb;8(1):66-73.

Women Infant and Children program participants' beliefs and consumption of soy milk : Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, University of Illinois, 238 Bevier Hall, 905 S. Goodwin Ave, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. alwheel2@illinois.edu

Abstract

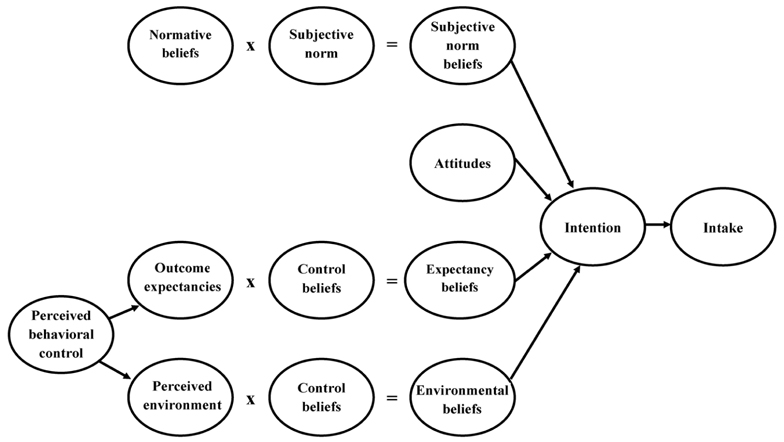

- The purpose of this study was to determine if Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) variables predict soy milk intake in a sample of WIC participants in 2 Illinois counties (n = 380). A cross-sectional survey was used, which examined soy foods intake, behavioral beliefs, subjective norms, motivation, and intention. Soy product intake was low at both sites, and many participants (40%) did not know that soy milk was WIC approved. Most (> 70%) wanted to comply with their health care providers, but didn't know their opinions about soy milk (50-66%). Intention was significantly correlated with intake (0.507, P < or = 0.01; 0.308, P < or = 0.05). Environmental beliefs (0.282 and 0.410, P < or = 0.01) and expectancy beliefs (0.490 and 0.636, P < or = 0.01) were correlated with intention. At site 1, 30% of the variance in intention to consume soy milk was explained by expectancy beliefs and subjective norm beliefs (P < 0.0001); at site 2, 40% of the variance in intention was explained by expectancy beliefs. The TPB variables of expectancy beliefs predicted intention to consume soy milk in WIC participants. Therefore, knowing more about the health benefits of soy and how to cook with soy milk would increase WIC participants' intention to consume soy milk. Positive messages about soy milk from health care providers could influence intake.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Oliveira V, Frazão E. The WIC Program Background, Trends, and Economic Issues, 2009 Edition. Economic Research Report Number 73. Washington D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture;2009.2. Kim CI, Lee Y, Kim BH, Lee HS, Jang YA. Development of supplemental nutrition care program for women, infants and children in Korea: NutriPlus. Nutr Res Pract. 2009; 3:171–179.

Article3. Suitor CW. Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. National Academies Press (US). Planning a WIC Research Agenda: Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press;2011.4. Institute of Medicine, Committee to Review the WIC Food Packages (US). WIC Food Packages: Time for a Change. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press;2006.5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture (US). Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office;2005.6. Zhao Y, Martin BR, Weaver CM. Calcium bioavailability of calcium carbonate fortified soymilk is equivalent to cow's milk in young women. J Nutr. 2005; 135:2379–2382.

Article7. Matthews VL, Knutsen SF, Beeson WL, Fraser GE. Soy milk and dairy consumption is independently associated with ultrasound attenuation of the heel bone among postmenopausal women: the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr Res. 2011; 31:766–775.

Article8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services (US). Food Labeling: Health Claims; Soy Protein and Coronary Heart Disease [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration;1999. 10. 26. cited 2012 Feb 21. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1999-10-26/pdf/99-27693.pdf.9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (US). Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21: Food and Drugs [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration;2011. cited 2012 Feb 21. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=101.82.10. Food Research and Action Center (US). New WIC Food Packages Proposed [Internet]. Washington D.C.: Food Research and Action Center;2006. cited 2012 Feb 21. Available from: http://frac.org/new-wic-food-packages-proposed/.11. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (US). Special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children (WIC): revisions in the WIC food packages; interim rule. Fed Regist. 2007; 72:68965–69032.12. Ajzen I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior. Chicago (IL): Dorsey Press;1988.13. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991; 50:179–211.

Article14. Patch CS, Tapsell LC, Williams PG. Overweight consumers' salient beliefs on omega-3-enriched functional foods in Australia's Illawarra region. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005; 37:83–89.

Article15. Robinson R, Smith C. Integrating issues of sustainably produced foods into nutrition practice: a survey of Minnesota Dietetic Association members. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003; 103:608–611.

Article16. Pawlak R, Connell C, Brown D, Meyer MK, Yadrick K. Predictors of multivitamin supplement use among African-American female students: a prospective study utilizing the theory of planned behavior. Ethn Dis. 2005; 15:540–547.17. Verbeke W, Vackier I. Individual determinants of fish consumption: application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2005; 44:67–82.

Article18. Eto K, Koch P, Contento IR, Adachi M. Variables of the Theory of Planned Behavior are associated with family meal frequency among adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011; 43:525–530.

Article19. Rah JH, Hasler CM, Painter JE, Chapman-Novakofski KM. Applying the theory of planned behavior to women's behavioral attitudes on and consumption of soy products. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004; 36:238–244.

Article20. Li S, Camp S, Finck J, Winter M, Chapman-Novakofski K. Behavioral control is an important predictor of soy intake in adults in the USA concerned about diabetes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010; 19:358–364.21. Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill;1978.22. Wenrich TR, Cason KL. Consumption and perceptions of soy among low-income adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004; 36:140–143.

Article23. Black MM, Hurley KM, Oberlander SE, Hager ER, McGill AE, White NT, Quigg AM. Participants' comments on changes in the revised special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children food packages: the Maryland food preference study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009; 109:116–123.

Article24. Ritchie LD, Whaley SE, Spector P, Gomez J, Crawford PB. Favorable impact of nutrition education on California WIC families. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010; 42:S2–S10.

Article25. Lee MJ, Park OJ. Soy food intake behavior by socio-demographic characteristics of Korean housewives. Nutr Res Pract. 2008; 2:275–282.

Article26. Pawlak R, Colby S, Herring J. Beliefs, benefits, barriers, attitude, intake and knowledge about peanuts and tree nuts among WIC participants in eastern North Carolina. Nutr Res Pract. 2009; 3:220–225.

Article27. Fung EB, Ritchie LD, Walker BH, Gildengorin G, Crawford PB. Randomized, controlled trial to examine the impact of providing yogurt to women enrolled in WIC. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010; 42:S22–S29.

Article28. Nolan-Clark DJ, Neale EP, Probst YC, Charlton KE, Tapsell LC. Consumers' salient beliefs regarding dairy products in the functional food era: a qualitative study using concepts from the theory of planned behaviour. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:843.

Article29. Lv N, Brown JL. Impact of a nutrition education program to increase intake of calcium-rich foods by Chinese-American women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011; 111:143–149.

Article30. Provencher V, Polivy J, Herman CP. Perceived healthiness of food. If it's healthy, you can eat more! Appetite. 2009; 52:340–344.

Article31. Schyver T, Smith C. Reported attitudes and beliefs toward soy food consumption of soy consumers versus nonconsumers in natural foods or mainstream grocery stores. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2005; 37:292–299.

Article32. Illinois Department of Human Services (US). WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List [Internet]. Springfield (IL): Illinois Department of Human Services;2013. cited 2013 Apr 20. Available from: http://www.peoriacounty.org/download?path=/pcchd/IllinoisWICFoodList.pdf.33. Illinois Department of Human Services (US). WIC Formula and Medical Nutritional Prescriptions [Internet]. Springfield (IL): Illinois Department of Human Services;2013. cited 2013 Apr 20. Available from: http://www.dhs.state.il.us/page.aspx?item=45972.34. National Cancer Institute. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health (US). Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. NIH Publication No. 05-3896 [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute;2005. 09. cited 2013 Sep 5. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/theory.pdf.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Predicting Exercise Behavior in Middle-aged Women: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior

- A case of necrotizing enterocolitis associated with cow and soy milk intolerance

- A Study of the Smoking Cessation Behavior of University Student: Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior, Self Efficacy, Health Locus of Control

- Implementation and Evaluation of Nutrition Education Programs Focusing on Increasing Vegetables, Fruits and Dairy Foods Consumption for Preschool Children

- Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Prediction and Intention of Smoking Cessation Behavior