J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2009 Dec;50(12):1892-1897. 10.3341/jkos.2009.50.12.1892.

Secondary Glaucoma and Sclerokeratitis After Cosmetic Eye Whitening by Regional Conjunctivectomy with Mitomycin C Application

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Olsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea. yimjinho@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2213005

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2009.50.12.1892

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To report a case of secondary glaucoma and sclerokeratitis after cosmetic eye whitening by regional conjunctivectomy with Mitomycin C application.

CASE SUMMARY

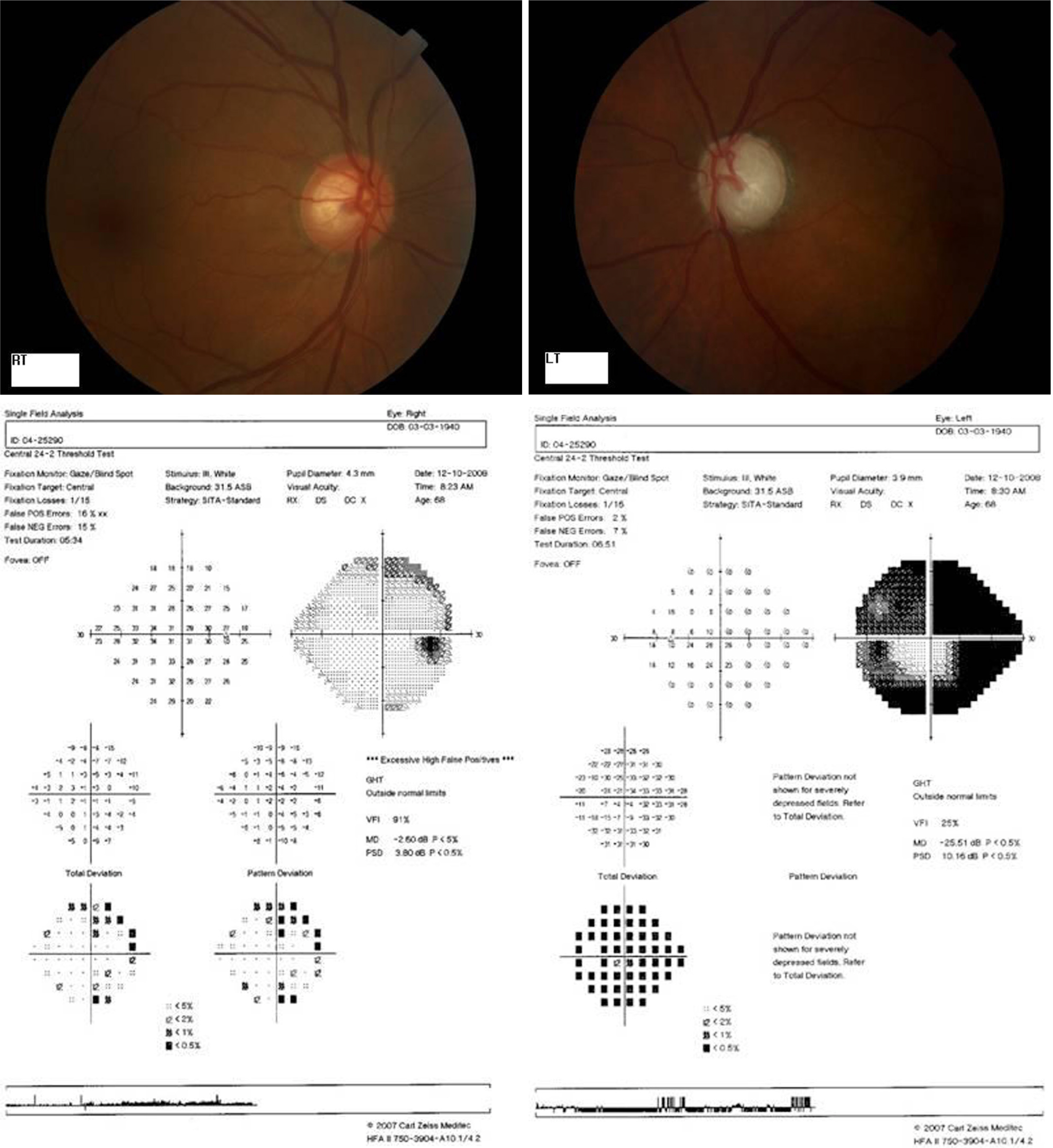

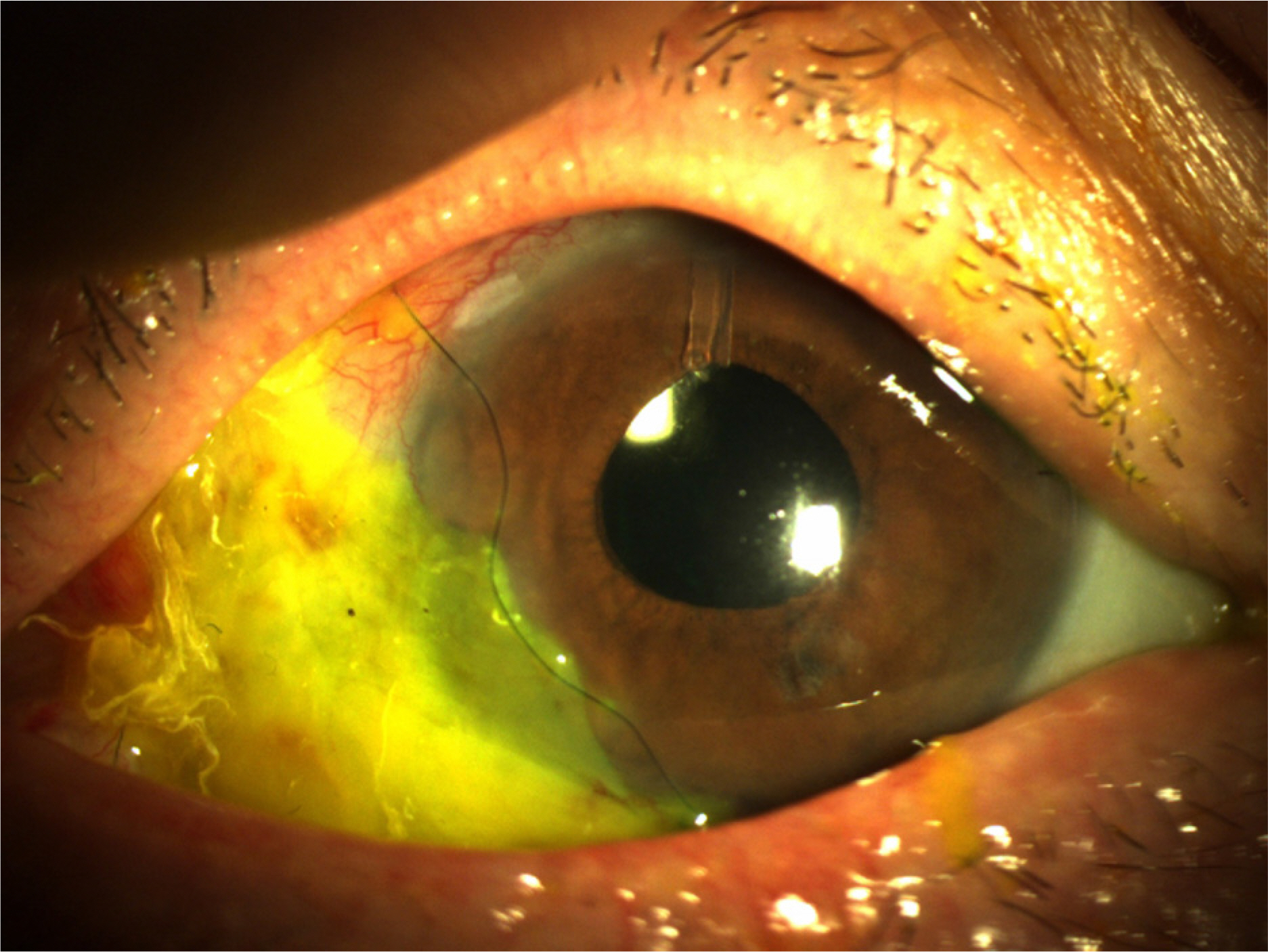

A 69 year-old man was referred to our clinic for a left ocular pain and ocular hypertension sustained for 3 months after cosmetic eye whitening by regional conjunctivectomy with Mitomycin C application for chronic conjunctival hyperemia. On first examination, the scleromalacia and large conjunctival epithelium defect in the nasal quadrant of the limbus area and diffuse sclerokeratitis were observed. Conjunctival and episcleral vessel deficit were seen except superior 30% portion in the left eye. The anterior chamber depth in the left eye was very shallow compared to the right eye and cell reaction in the left anterior chamber was detected. Intraocular pressure (IOP) in the left eye was 28 mmHg after Cosopt(R) and 15% mannitol 500 ml use. Glaucomatous cupping was detected. During follow-up, left IOP increased over 40 mmHg despite the maximal medical treatment and the progression of visual field defects was detected, so then left phacoemulsification, Ahmed valve implantation and amnion membrane transplantation were done. After surgery, the conjunctival epithelial defect and sclerokeratitis were improved much and IOP was regulated 20~30 mmHg without medication. Digital massage was done 2 times per day for decreasing IOP and wound remodeling after 1 month. At 3 month after surgery, the conjunctival epithelial defect recurred and scleromalacia was also progressed, so then we performed autoconjunctival flap and amnion membrane transplantation in left eye. The conjunctival epithelial defect were recovered completely, IOP was regulated 24~36 mmHg without medication, and 20~24 mmHg with Cosopt.(R) The compliance of patient is very poor, further management may be needed for IOP control.

CONCLUSIONS

Cosmetic eye whitening by regional conjunctivectomy with Mitomycin C application can cause serious complications such as scleromalcia and secondary glaucoma. This case shows that particular care should be taken in order to minimize these complications.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Jaros PA, DeLuise VP. Pingueculae and pterygia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988; 33:41–9.

Article2. Austin P, Jakobiec FA, Iwamoto T. Elastodysplasia and elastodystrophy as the pathologic bases of ocular pterygia and pingueculae. Ophthalmology. 1983; 90:96–109.3. Pinkerton OD, Hokama Y, Shigemura LA. Immunologic basis for the pathogenesis of pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984; 98:225–8.

Article4. Wong WW. A hypothesis on the pathogenesis of pterygium. Ann Ophthalmol. 1978; 10:303–8.5. Frucht-Pery J, Siganos CS, Solomon A, et al. Topical indomethacin solution versus dexamethasone solution for treatment of inflamed pterygium and pinguecula: a prospective randomized clinical study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999; 127:148–52.

Article6. Tarr KH, Constable IJ. Late complications of pterygium treatment. Br J Opthalmol. 1980; 64:496–505.

Article7. Rubinfeld RS, Pfister RR, Stein RM, et al. Serious complications of topical mitomycin-C after pterygium surgery. Opthalmology. 1992; 99:1647–54.

Article8. Oum BS, Lee JS. The effect of mitomycin C on inhibition of cellular proliferation and type-1 collagen, Laminin synthesis of pterygium mesenchymal cell. J Korean Opthalmol Soc. 1999; 40:712–20.9. Willems EW, Nooter K, Verweij J. Antitumor antibiotics. In: Chabner BA, Longo DL eds. Cancer chemotherapy & biotherapy: principles and practice. 4th ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2006. 1:chap. 16.10. Kim JH, Lee HB, Yoon DK. Scleral grafts for the cases of sclera perforation, sclera ectasia and sclera necrosis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1978; 19:55–61.11. Song HY, Im JS, Kwak JY. Acellular dermal allograft transplantation in patients with scleromalacia after pterygium excision. J Korean Opthalmol Soc. 2008; 49:1685–9.

Article12. Na YS, Joo MJ, Kim JH. Results of sclera allograftind on sclera necrosis following pterygium excision. J Korean Opthalmol Soc. 2005; 46:402–9.13. Wan norliza WM, Raihan IS, Azwa JA, Ibrahim M. Scleral melting 16 years after pterygium excision with topical mitomycin C adjuvant therapy. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2006; 29:165–7.

Article14. Anduze AL, Burnett JM. Indications for and complications of mitomycin-C in pterygium surgery. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1996; 27:667–73.

Article15. Brooks AM, Robertson IF, Mahoney AM. Ocular rigidity and intraocular pressure in keratoconus. Aust J Ophthalmol. 1984; 12:317–24.

Article16. Nessim M, Kyprianou I, Kumar V, Murray PI. Anterior scleritis, scleral thinning, and intraocular pressure measurement. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005; 13:455–7.

Article17. Jorgensen JS, Guthoff R. The role of episcleral venous pressure in the development of secondary glaucoma. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1988; 193:471–5.18. Ruiz-Ederra J, Verkman AS. Mouse model of sustained elevation in intraocular pressure produced by episcleral vein occlusion. Exp Eye Res. 2006; 82:879–84.

Article19. Danias J, Shen F, Kavalarakis M, et al. Characterization of retinal damage in the episcleral vein cauterization rat glaucoma model. Exp Eye Res. 2006; 82:219–28.

Article20. Mittag TW, Danias J, Pohorenec G, et al. Retinal damage after 3 to 4 months of elevated intraocular pressure in a rat glaucoma model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41:3451–9.21. Urcola JH, Hernández M, Vecino E. Three experimental glaucoma models in rats: comparison of the effects of intraocular pressure elevation on retinal ganglion cell size and death. Exp Eye Res. 2006; 83:429–37.

Article22. Shareef SR, Garcia-Valenzuela E, Salierno A, et al. Chronic ocular hypertension following episcleral venous occlusion in rats. Exp Eye Res. 1995; 61:379–82.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Treatment of Scleromalacia with Scleral Autograft

- The Development of Scleromalacia after Regional Conjunctivectomy with the Postoperative Application of Mitomycin C as an Adjuvant Therapy

- Effect of Intraoperative Mitomycin C in High-risk Glaucoma Filtering Surgery

- The Effect of Mitomycin on the Experimental Filtering Surgery

- Comparison of Outcome of Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C and Ahmed Valve Implantation for Uveitic Glaucoma