J Korean Soc Spine Surg.

2001 Sep;8(3):314-320. 10.4184/jkss.2001.8.3.314.

Classification and Imaging Study of the Lumbar Disc Herniation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hwanlee@yumc.yonsei.ac.kr

- KMID: 2209751

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4184/jkss.2001.8.3.314

Abstract

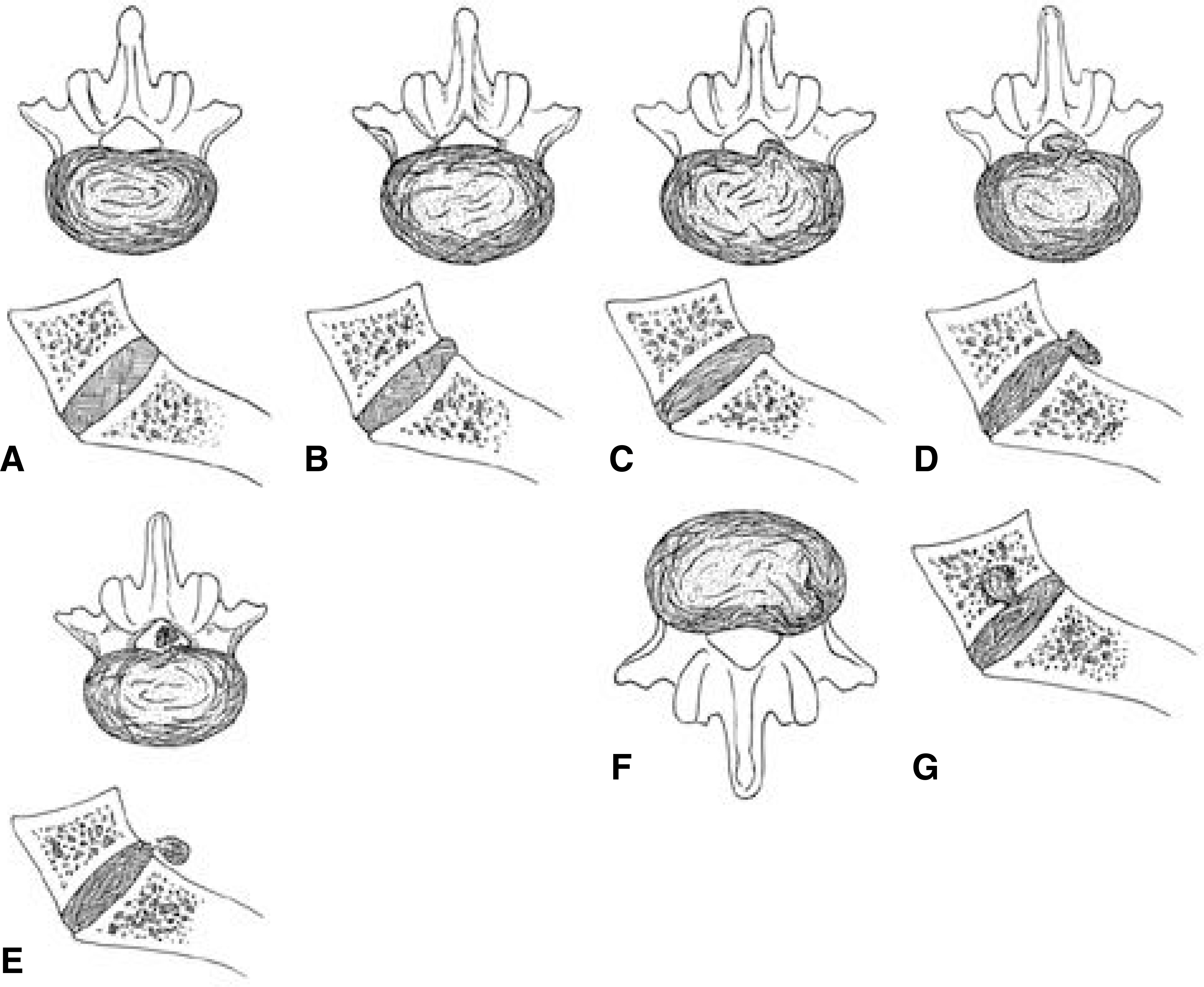

- It is known that the lifetime prevalence of low back pain approximates 80%, with long standing low back problems in roughly 10% to 20% of the population. The symptoms of sciatica due to nerve root compression most often relate to aberration of the lumbar intervertebral disc. Lumbar disc herniation is defined as herniation of nucleus and/or anulus fibrosus through the tear of the anulus fibrosus. According to the degree, it has been classified as a bulging disc, a protruded disc, a extruded disc, and a sequestrated disc. Also it has been classified as central, posterolateral, and foraminal herniation by the location of the herniation. The four imaging studies most frequently ordered to evaluate lumbar disc herniation are plain x-ray films, myelography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Each test provides useful information about lumbar disc herniation. However, before the selection of a test, the category of the clinical problem must be defined and imaging abnormalities must be correlated with historical and physical findings. Many errors in decision making with imaging studies of lumbar disc herniation do not come from misinterpretation of what in seen on the images; instead, they are related to how the imaging information is used and integrated into the clinical decision-making process.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Relationship Between Preoperative MRI Findings and Clinical Outcomes in Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation

Seung-Hwan Lee, Hyuck-Min Kwon, Tae-Hwan Yoon, Seong-Hwan Moon, Hwan-Mo Lee

J Korean Soc Spine Surg. 2014;21(1):24-29. doi: 10.4184/jkss.2014.21.1.24.

Reference

-

1). Aguila A, Piraino D, Modic MT. Intranuclear cleft of the intervertebral disc: Magnetic resonance imaging. Radiology. 155:155–158. 1985.2). Bates D, Ruggieri P. Imaging modalities for evaluation of the spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 29:675–690. 1991.3). Boden S, Davies D, Dina T et al.Abnormal magnetic resonance scan in asymptomatic subject. J Bone J Surg. 72A:403–408. 1990.4). Bundschuh W, Modic MT, Ross JS et al.Epidural fibro-sis and recurrent disc herniation in the lumbar spine. AJNR. 9:169–178. 1988.5). Dandy WE. Ventriculography following injection of air into cerebral ventricles. Ann Surg. 11:5. 1918.6). Fardon DF, Pinkerton S, Balderston R et al.Terms used for diagnosis by English-speaking spine surgeons. Spine. 18:272–277. 1993.7). Forristal RM, Marsh HO, Pay NT. MRI & CT of the lumbar spine. Comparison of diagnotic methods and correlation with surgical findings. Spine. 13:1049–1054. 1988.8). Hesselink JR. Spine imaging: History, achievement, re-maining frontiers. Am J Roentgenol. 140:1223–1229. 1988.9). Jackson RPand Glah JJ. Foraminal and extraforaminal lumbar disc herniation: Diagnosis and treatment. Spine. 12:577–585. 1987.

Article10). Joubert JM, Laredo JD, Ziza JM. Gadolinium enhanced MR imaging in preoperative evaluation lumbar disc herniation. Radiology. 185:153. 1992.11). Junichi K, Mitsuo H. Diagnosis and operative treatment of intraforaminal and extraforaminal nerve root compression. Spine. 16:1312–1320. 1991.

Article12). Kim NH, Lee HM. Textbook of Spinal Surgery. 1st ed. Seoul: Euihak moonhwasa;p. 175–176. 1998.13). Mansfield P, Maudsly A. Medical imaging by NMR. Br J Radiol. 50:188–194. 1977.

Article14). McCulloch JA, Inoue S, Moriya H et al.Surgical indications and techniques. Weinstein JN, Wiesel SW, editors. The Lumbar Spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;1990.15). Modic MT, Masaryk T, Boumphrey F et al.Lumbar herniated disc disease and canal stenosis. AJNR. 7:709–717. 1986.16). Nachemson AL. The lumbar spine: An orthopaedic challenge. Spine. 1:59–71. 1976.

Article17). Park BM, Kim NH, Koh YK. Myelography in the lumbar disc herniations. J Kor Orthop Asso. 18:550–557. 1983.18). Suk SI. Spinal Surgery. 1st ed. Seoul: Choisineuihak sa;p. 190–191. 1997.

Article19). Suk SI. Orthopaedisc. 5th ed. Seoul: Choisineuihak sa;p. 451–454. 1998.20). Wiesel SW, Tsourmas N, Feffer HL. A study of com -puter-assisted tomography. I. The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine. 9:549–551. 1984.21). Yu S, Haughton VM, Sether LA, Wagner M. Anulus fibrosus in bulging intervertebral disks. Radiology. 169:761–763. 1988.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Analysis of Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniation

- Rapid Repeated Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniation after Microscopic Discectomies

- The Relationship between the Lower Lumbar Disc Herniation and the Morphology of the Iliolumbar Ligaments Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Juvenile Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Herniation: Five Cases Report

- Spinal Nerve Root Swelling Mimicking Intervertebral Disc Herniation in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Case Report