J Korean Acad Conserv Dent.

2004 Nov;29(6):541-547. 10.5395/JKACD.2004.29.6.541.

A comparison of the length between mesio-buccal and mesio-lingual canals of the mandibular molar

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Conservative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Chosun University, Korea. rootcanal@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2175655

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5395/JKACD.2004.29.6.541

Abstract

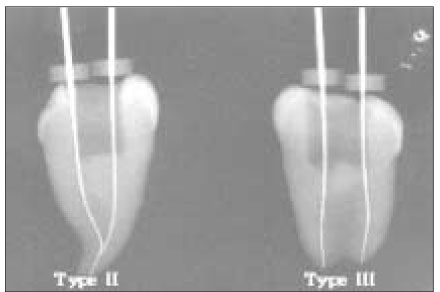

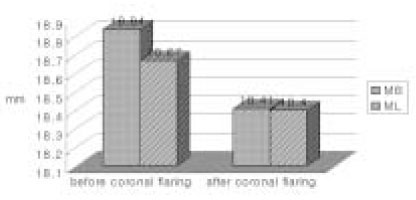

- The aim of this study was to compare the initial apical file (IAF) length between the mesio-buccanl and mesio-lingual canals of the mandibular molar before and after early coronal flaring. Fifty mandibular molars with complete apical formation and patent foramens were selected. After establishing the initial working length of the buccal and lingual canal of the mesial root using the Root-ZX, radiographs were taken for the working length with a 0.5 mm short of #15 K-file tip just visible at the foramen under a surgical microscope (OPMI 1-FC, Carl Zeiss Co. Germany) at 25X. After early coronal flaring using the K3 file, additional radiographs were taken using the same procedure. The root canal morphology and the difference in working length between the buccal and lingual canals were evaluated. These results show that the difference in the length between the mesio-buccal and mesio-lingual canals of the mandibular molar was < or = 0.5 mm. If one canal has a correct working length for the mesial root of the mandibular molar, it can be used effectively for measuring the working length of another canal when the files are superimposed or loosening. In addition, the measured the working length after early coronal flaring is much more reasonable because the difference in the length between the mesio-buccal and mesio-lingual canals can be reduced.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Study of endodontic working length of Korean posterior teeth

Jeong-Yeob Kim, Sang-Hoon Lee, Gwang-Hee Lee, Sang-Hyuk Park

J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2010;35(6):429-435. doi: 10.5395/JKACD.2010.35.6.429.

Reference

-

1. Lim SS. Clinical Endodontics. 1999. 2nd ed. Seoul: Dentistry Magine;122–127.2. Ingle J, Bakland L. Endodontics. 1985. 3th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;36–37.3. Kuttler Y. Microcopic investigation of root apexes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1955. 50:544–552.4. Altman M. Apical root anatomy of human maxillary central incisors. Oral Surg. 1970. 30:694–699.5. Burch JG, Hulen S. The relationship of the apical foramen to the anatomic apex of the tooth root. Oral Surg. 1972. 34:262–267.

Article6. Burch JG, Hulen S. The relationship of the apical foramen to the anatomic apex of the tooth root. Oral Surg. 1972. 34:262–268.

Article7. Green D. A stereomicroscopic study of the root apices of 400 maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth. Oral Surg. 1956. 9:1224–1232.

Article8. Green D. Stereomicroscopic study of 700 root apices of maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth. Oral Surg. 1960. 13:728–733.

Article9. Gutierrez JH, et al. Apical foraminal openings in human teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995. 79:769–777.

Article10. Morfis A, et al. Study of the apices of human permanent teeth with the use of a scanning electron microscope. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994. 77:172–176.

Article11. Goldman M, et al. Reliability of radiographic interpretations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974. 38:287–293.

Article12. Cohen S, Burns R. Pathways of the pulp. 1988. 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby;248–251.13. Wheeler RC. Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion. 1974. 5th ed. W.B. Saunders Co;267–297.14. Grossman L. Endodontic practice. 1988. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;169–173.15. Ingle JI, Bakland LK. Endodontics. 2002. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;462–469.16. Cohen S, Burns R. Pathways of the pulp. 2002. 8th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby;210–217.17. Weine FS. Endodontic therapy. 1982. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Co;209.18. Woelfel JG, Scheid RC. Dental Anatomy. 2002. 1st ed. philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins;97–107.19. Pineda F, Kuttler Y. Mesiodistal and buccolingual roentgenographic investigation of 7,275 root canals. Oral Surg. 1972. 33:101–110.

Article20. Green D, Brooklyn NY. Double canals in single roots. Oral Surg. 1973. 35:689–696.

Article21. Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg. 1984. 58:589–599.

Article22. Blayney JR. Some factors in root canal treatment. J Dent Res. 1924. 11:840.23. Groove CJ. Faculty technic in investigations of the apices of pulpless teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1926. 13:746.24. Katz A, et al. Tooth length determination; A review. Oral Surg. 1991. 72:238–242.

Article25. Kobayashi C, Suda H. New Electronic canal length measuring device on the ratio method. J Endod. 1994. 20:111–114.26. Cohen S, Burns R. Pathways of the pulp. 1994. 6th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby;179–218.27. Hwang HG, Shin YG, Kim PS. A study on the accuracy of the root-zx according to the various conditions of root canals. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2000. 25:474–482.28. Hulsmann M, et al. An improved technique for the evaluation of root canal preparation. J Endod. 1999. 25:599–602.

Article29. Hwang HG, Shin YG. The effectiveness of obturating techniques in sealing isthmuses. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent. 2001. 26:499–506.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Study of Root Canals Morphology in Primary Molars using Computerized Tomography

- An accuracy of the several electronic apex locators on the mesial root canal of the mandibular molar

- Endodontic treatment of mandibular molar with root dilaceration using Reciproc single-file system

- Evaluation of mandibular cortical bone thickness for placement of temporary anchorage devices (TADs)

- The Morphology of the Mandibular Canal in Korean