Ann Dermatol.

2015 Aug;27(4):417-422. 10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.417.

Delayed Reconstruction for the Non-Amputative Treatment of Subungual Melanoma

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Dermatology, Severance Hospital, Cutaneous Biology Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. kychung@yuhs.ac

- 2Department of Dermatology, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2171499

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.417

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

In cases of early stage subungual melanoma (SUM), conservative treatment with non-amputative wide excision of the nail unit and subsequent skin graft is preferred over amputation to preserve the involved digit.

OBJECTIVE

We report a series of patients with SUM treated with conservative surgery and suggest an effective supplementary treatment process.

METHODS

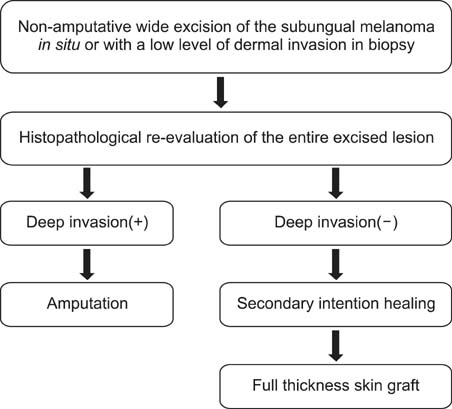

We retrospectively reviewed 10 patients (2 males, 8 females) who were diagnosed with in situ or minimally invasive SUM on the first biopsy and underwent non-amputative wide excision of the nail unit. All patients underwent secondary intention healing during the histopathological re-evaluation of the entire excised lesion, and additional treatment was administered according to the final report.

RESULTS

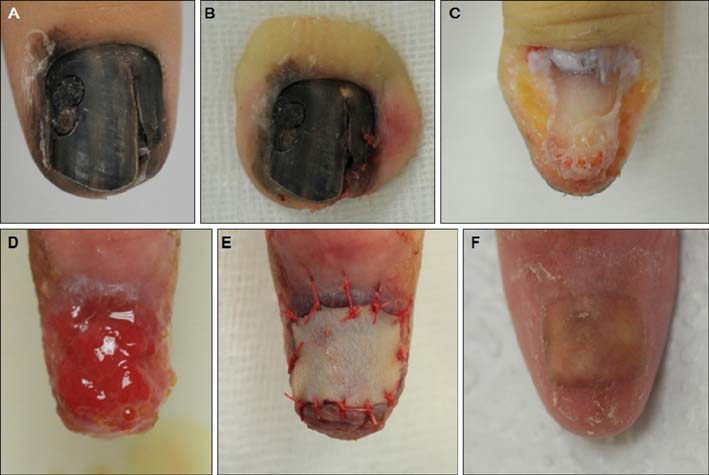

In two of 10 patients, amputation was performed because of the detection of deep invasion (Breslow thickness: 4.0, 2.3 mm) from the final pathologic results, which differed from the initial biopsy. In six patients who received delayed skin graft, the mean total time required for complete healing after secondary intention healing and the skin graft was 66.83+/-15.09 days. As a result of this delayed skin graft, the final scarring was similar to the original shape of the nail unit, scored between 5 and 10 on a visual analogue scale. Most patients were satisfied with this conservative surgery except one patient, who had volar portion involvement and received an interpolated flap instead of a skin graft.

CONCLUSION

Our treatment process can reduce the risk of incomplete resection and improve cosmetic outcomes in patients with SUM.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Centennial History of Yonsei University Dermatology in Korea: 1917 to 2017

Jihee Kim, Tae-Gyun Kim, Si Hyung Lee, Min Kyung Lee, Jong Hoon Kim, Sang Eun Lee, Do Young Kim, Mi Ryung Roh, Chang Ook Park, Ju Hee Lee, Min-Geol Lee, Dongsik Bang, Sang Ho Oh, Kee Yang Chung

Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(5):513-521. doi: 10.5021/ad.2018.30.5.513.

Reference

-

1. Möhrle M, Häfner HM. Is subungual melanoma related to trauma? Dermatology. 2002; 204:259–261.

Article2. Rex J, Paradelo C, Mangas C, Hilari JM, Fernández-Figueras MT, Ferrándiz C. Management of primary cutaneous melanoma of the hands and feet: a clinicoprognostic study. Dermatol Surg. 2009; 35:1505–1513.3. Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, McCarthy SW, Shaw HM, Quinn MJ, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential pitfalls in diagnosis, and guidelines for histologic reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:1902–1912.4. Park KG, Blessing K, Kernohan NM. The Scottish Melanoma Group. Surgical aspects of subungual malignant melanomas. Ann Surg. 1992; 216:692–695.

Article5. Quinn MJ, Thompson JE, Crotty K, McCarthy WH, Coates AS. Subungual melanoma of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1996; 21:506–511.

Article6. Heaton KM, el-Naggar A, Ensign LG, Ross MI, Balch CM. Surgical management and prognostic factors in patients with subungual melanoma. Ann Surg. 1994; 219:197–204.

Article7. Merle M. Reconstruction of amputated thumb: 20 years of development of techniques and indications. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1996; 180:195–210. discussion 211-2148. Sureda N, Phan A, Poulalhon N, Balme B, Dalle S, Thomas L. Conservative surgical management of subungual (matrix derived) melanoma: report of seven cases and literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 165:852–858.

Article9. Clarkson JH, McAllister RM, Cliff SH, Powell B. Subungual melanoma in situ: two independent streaks in one nail bed. Br J Plast Surg. 2002; 55:165–167.

Article10. Haneke E, Baran R. Longitudinal melanonychia. Dermatol Surg. 2001; 27:580–584.

Article11. Nguyen JT, Bakri K, Nguyen EC, Johnson CH, Moran SL. Surgical management of subungual melanoma: mayo clinic experience of 124 cases. Ann Plast Surg. 2013; 71:346–354.12. Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W, Garbe C, Rassner G, Breuninger H. "Functional" surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003; 29:366–374.

Article13. Izumi M, Ohara K, Hoashi T, Nakayama H, Chiu CS, Nagai T, et al. Subungual melanoma: histological examination of 50 cases from early stage to bone invasion. J Dermatol. 2008; 35:695–703.

Article14. Stewart CL, Rubin AI. Update: nail unit dermatopathology. Dermatol Ther. 2012; 25:551–568.

Article15. Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L, Cook M, Corrie PG, Cox NH, et al. British Association of Dermatologists Clinical Standards Unit. Revised U.K. guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 163:238–256.

Article16. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, Foote Hood A, Grichnik JM, Swetter SM, et al. American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 65:1032–1047.

Article17. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, Bichakjian CK, Carson WE 3rd, Daud A, et al. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Melanoma, version 2. 2013: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013; 11:395–407.18. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Bichakjian CK, Dilawari RA, Dimaio D, Guild V, et al. NCCN Melanoma Panel. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009; 7:250–275.

Article19. Baer SC, Schultz D, Synnestvedt M, Elder DE. Desmoplasia and neurotropism. Prognostic variables in patients with stage I melanoma. Cancer. 1995; 76:2242–2247.

Article20. Hoigné D, Hug U, Schürch M, Meoli M, von Wartburg U. Semi-occlusive dressing for the treatment of fingertip amputations with exposed bone: quantity and quality of soft-tissue regeneration. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014; 39:505–509.

Article21. de Boer P, Collinson PO. The use of silver sulphadiazine occlusive dressings for finger-tip injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981; 63B:545–547.

Article22. Mennen U, Wiese A. Fingertip injuries management with semi-occlusive dressing. J Hand Surg Br. 1993; 18:416–422.

Article23. Muneuchi G, Tamai M, Igawa K, Kurokawa M, Igawa HH. The PNB classification for treatment of fingertip injuries: the boundary between conservative treatment and surgical treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 2005; 54:604–609.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Non-amputative Surgical Management of Subungal Melanoma in Situ

- Subungual Melanoma of Left Thumb: A Case Report

- A Case of Amelanotic Subungual Melanoma

- Three Cases of Nail Matrix Nevus in Children

- Long-term results of wide local excision with concurrent venous free flap reconstruction in subungual melanoma