Anesth Pain Med.

2016 Jan;11(1):91-98. 10.17085/apm.2016.11.1.91.

Comparison of warming methods for core temperature preservation during total knee arthroplasty using a pneumatic tourniquet

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hsyang@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 2169082

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2016.11.1.91

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

It is important to ensure that patients are normothermic during surgery. In total knee arthroplasty, the pneumatic tourniquet affects body temperature. We compared the ability of two warming devices to preserve core temperature in patients using a lower limb tourniquet under general anesthesia.

METHODS

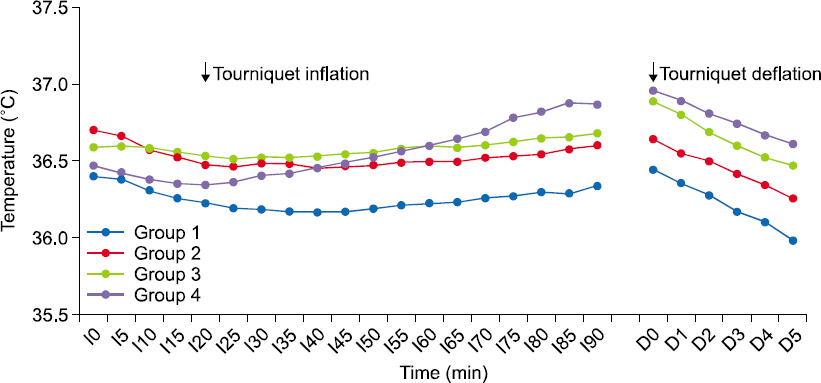

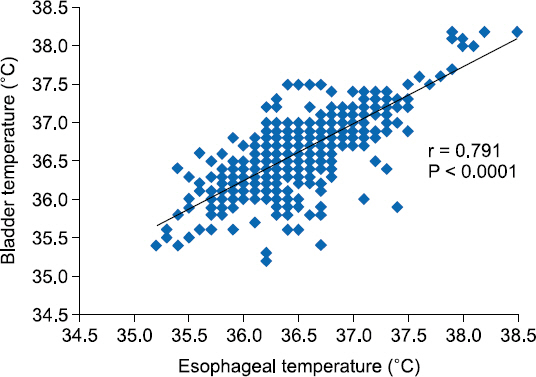

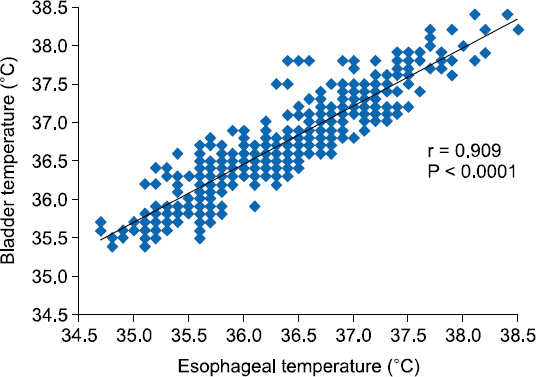

We included 132 patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I-II who were scheduled to undergo total knee arthroplasty. The patients were randomly divided into four groups (n = 33): group 1, without any heating method; group 2, with fluid warming; group 3, with forced-air warming; and group 4, with a combination of the two heating methods. After the induction of anesthesia, the esophageal and urinary bladder temperatures were monitored and recorded every 5 min before tourniquet deflation and every 1 min after tourniquet deflation.

RESULTS

Before tourniquet deflation, compared with group 1, the odds ratios of groups 3 and 4 were less than 1. After tourniquet deflation, compared with group 1, the odds ratios of all groups using warming devices were less than 1. In particular, group 4 showed the largest hypothermia-preventive effect among the four groups. There was a significant correlation between esophageal temperature and bladder temperature before and after tourniquet deflation.

CONCLUSIONS

After tourniquet deflation, a combination of a fluid warmer and forced-air warmer is the most effective method to prevent hypothermia, although either a fluid warmer or forced-air warmer alone could help to prevent hypothermia. Urinary bladder temperature changes correlate well with esophageal temperature changes throughout this operation.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Girardis M, Milesi S, Donato S, Raffaelli M, Spasiano A, Antonutto G, et al. The hemodynamic and metabolic effects of tourniquet application during knee surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000; 91:727–31. DOI: 10.1097/00000539-200009000-00043. DOI: 10.1213/00000539-200009000-00043. PMID: 10960408.

Article2. Akata T, Kanna T, Izumi K, Kodama K, Takahashi S. Changes in body temperature following deflation of limb pneumatic tourniquet. J Clin Anesth. 1998; 10:17–22. DOI: 10.1016/S0952-8180(97)00214-6.

Article3. Estebe JP, Le Naoures A, Malledant Y, Ecoffey C. Use of a pneumatic tourniquet induces changes in central temperature. Br J Anaesth. 1996; 77:786–8. DOI: 10.1093/bja/77.6.786. PMID: 9014635.

Article4. Sanders BJ, D’Alessio JG, Jernigan JR. Intraoperative hypothermia associated with lower extremity tourniquet deflation. J Clin Anesth. 1996; 8:504–7. DOI: 10.1016/0952-8180(96)00114-6.

Article5. Sessler DI. Perioperative heat balance. Anesthesiology. 2000; 92:578–96. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00042. PMID: 10691247.

Article6. Modig J, Kolstad K, Wigren A. Systemic reactions to tourniquet ischaemia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1978; 22:609–14. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1978.tb01344.x. PMID: 726866.

Article7. Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of wound infection and temperature group. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1209–15. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341901. PMID: 8606715.8. Roth JV. Some unanswered questions about temperature management. Anesth Analg. 2009; 109:1695–9. DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b763ae. PMID: 19843812.

Article9. Rajagopalan S, Mascha E, Na J, Sessler DI. The effects of mild perioperative hypothermia on blood loss and transfusion requirement. Anesthesiology. 2008; 108:71–7. DOI: 10.1097/01.anes.0000296719.73450.52. PMID: 18156884.

Article10. Beilin B, Shavit Y, Razumovsky J, Wolloch Y, Zeidel A, Bessler H. Effects of mild perioperative hypothermia on cellular immune responses. Anesthesiology. 1998; 89:1133–40. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-199811000-00013. PMID: 9822001.

Article11. Buggy DJ, Crossley AW. Thermoregulation, mild perioperative hypothermia and postanaesthetic shivering. Br J Anaesth. 2000; 84:615–28. DOI: 10.1093/bja/84.5.615.

Article12. Forstot RM. The etiology and management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. J Clin Anesth. 1995; 7:657–74. DOI: 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00099-2.

Article13. Clark-Price SC, Dossin O, Jones KR, Otto AN, Weng HY. Comparison of three different methods to prevent heat loss in healthy dogs undergoing 90 minutes of general anesthesia. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2013; 40:280–4. DOI: 10.1111/vaa.12010. PMID: 23347363.

Article14. Hart SR, Bordes B, Hart J, Corsino D, Harmon D. Unintended perioperative hypothermia. Ochsner J. 2011; 11:259–70. PMID: 21960760. PMCID: PMC3179201.15. Kaye AD, Riopelle JM. Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Young WL, editors. Intravascular fluid and electrolyte physiology. Miller’s Anesthesia. 2010. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone;p. 1728. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-443-06959-8.00054-6.

Article16. Kim YS, Jeon YS, Lee JA, Park WK, Koh HS, Joo JD, et al. Intra-operative warming with a forced-air warmer in preventing hypothermia after tourniquet deflation in elderly patients. J Int Med Res. 2009; 37:1457–64. DOI: 10.1177/147323000903700521. PMID: 19930851.

Article17. Horowitz PE, Delagarza MA, Pulaski JJ, Smith RA. Flow rates and warming efficacy with hotline and ranger blood/fluid warmers. Anesth Analg. 2004; 99:788–92. DOI: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000129995.42008.A4. PMID: 15333412.

Article18. Fallis WM. The effect of urine flow rate on urinary bladder temperature in critically ill adults. Heart Lung. 2005; 34:209–16. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.10.001. PMID: 16015226.

Article19. Cork RC, Vaughan RW, Humphrey LS. Precision and accuracy of intraoperative temperature monitoring. Anesth Analg. 1983; 62:211–4. DOI: 10.1213/00000539-198302000-00016. DOI: 10.1097/00132586-198310000-00022.

Article20. Lefrant JY, Muller L, de La Coussaye JE, Benbabaali M, Lebris C, Zeitoun N, et al. Temperature measurement in intensive care patients: Comparison of urinary bladder, oesophageal, rectal, axillary, and inguinal methods versus pulmonary artery core method. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29:414–8. PMID: 12577157.

Article21. Fallis WM. Monitoring urinary bladder temperature in the intensive care unit: State of the science. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:38–45. PMID: 11785556.

Article22. Sato H, Yamakage M, Okuyama K, Imai Y, Iwashita H, Ishiyama T, et al. Urinary bladder and oesophageal temperatures correlate better in patients with high rather than low urinary flow rates during non-cardiac surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008; 25:805–9. DOI: 10.1017/S0265021508004602. PMID: 18538052.

Article23. Jeong SM, Hahm KD, Jeong YB, Yang HS, Choi IC. Warming of intravenous fluids prevents hypothermia during off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008; 22:67–70. DOI: 10.1053/j.jvca.2007.04.003. PMID: 18249333.

Article24. El-Gamal N, El-Kassabany N, Frank SM, Amar R, Khabar HA, El-Rahmany HK, et al. Age-related thermoregulatory differences in a warm operating room environment (approximately 26 degrees c). Anesth Analg. 2000; 90:694–8. DOI: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00034. PMID: 10702459.25. Morris RH. Operating room temperature and the anesthetized, paralyzed patient. Arch Surg. 1971; 102:95–7. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350020005002. PMID: 4250862.

Article26. Li C, Schmid S, Mason J. Effects of pre-cooling and pre-heating procedures on cement polymerization and thermal osteonecrosis in cemented hip replacements. Med Eng Phys. 2003; 25:559–64. DOI: 10.1016/S1350-4533(03)00054-7.

Article27. Fernandes LA, Braz LG, Koga FA, Kakuda CM, Modolo NS, de Carvalho LR, et al. Comparison of peri-operative core temperature in obese and non-obese patients. Anaesthesia. 2012; 67:1364–9. DOI: 10.1111/anae.12002.x. PMID: 23088746.

Article28. Kasai T, Hirose M, Matsukawa T, Takamata A, Tanaka Y. The vasoconstriction threshold is increased in obese patients during general anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003; 47:588–92. DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00097.x. PMID: 12699518.

Article29. Enriori PJ, Sinnayah P, Simonds SE, Garcia Rudaz C, Cowley MA. Leptin action in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue in spite of systemic leptin resistance. J Neurosci. 2011; 31:12189–97. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2336-11.2011. PMID: 21865462. PMCID: PMC3758545.

Article30. Ikeda T, Ozaki M, Sessler DI, Kazama T, Ikeda K, Sato S. Intraoperative phenylephrine infusion decreases the magnitude of redistribution hypothermia. Anesth Analg. 1999; 89:462–5. DOI: 10.1097/00000539-199908000-00040. DOI: 10.1213/00000539-199908000-00040. PMID: 10439767.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Body Core Temperature Change after Pneumatic Tourniquet Release during Inhalation Anesthesia

- Comparison of the efficacy of a forced-air warming system and circulating-water mattress on core temperature and post-anesthesia shivering in elderly patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia

- Change in the effect of rocuronium after pneumatic tourniquet release in patients undergoing unilateral total knee arthroplasty

- The Effects of Tourniquet Pressure on the Postoperative Thigh Pain and Blood Loss in Total Knee Arthroplasty

- Vital sign changes associated with tourniquet use under spinal anesthesia for total knee arthroplasty