J Korean Med Sci.

2013 Jun;28(6):848-854. 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.848.

Health-Related Quality-of-Life after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with UA/NSTEMI and STEMI: the Korean Multicenter Registry

- Affiliations

-

- 1Cardiovascular Center, Incheon St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Incheon, Korea. coronary@catholic.ac.kr

- 2Cardiac and Vascular Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Division of Cardiology, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Cardiovascular Center, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory & Coronary Intervention, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Cardiology, Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, Korea.

- KMID: 2158031

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.848

Abstract

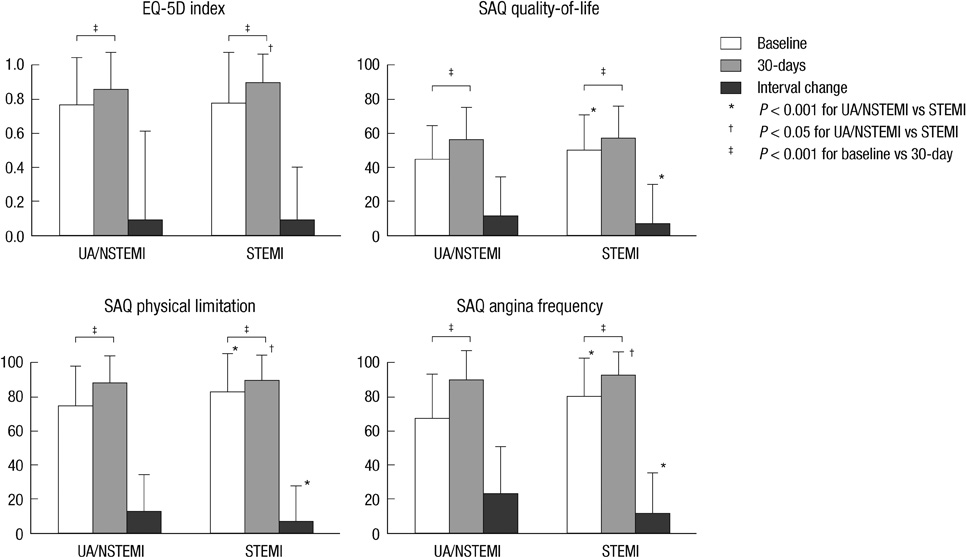

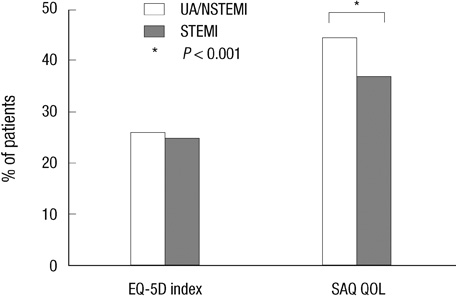

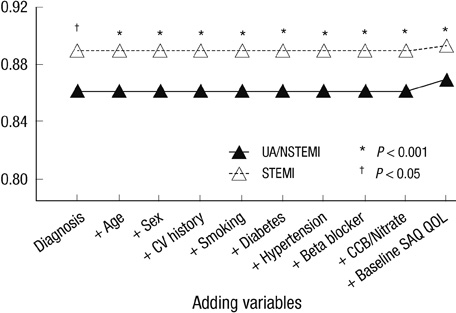

- Compared with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), long-term outcomes are known to be worse in patients with unstable angina/non-STEMI (UA/NSTEMI), which might be related to the worse health status of patients with UA/STEMI. In patients with UA/NSTEMI and STEMI underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), angina-specific and general health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) was investigated at baseline and at 30 days after PCI. Patients with UA/NSTEMI were older and had higher frequencies in female, diabetes and hypertension. After PCI, both angina-specific and general HRQOL scores were improved, but improvement was much more frequent in angina-related HRQOL of patients with UA/NSTEMI than those with STEMI (44.2% vs 36.8%, P < 0.001). Improvement was less common in general HRQOL. At 30-days after PCI, angina-specific HRQOL of the patients with UA/NSTEMI was comparable to those with STEMI (56.1 +/- 18.6 vs 56.6 +/- 18.7, P = 0.521), but general HRQOL was significantly lower (0.86 +/- 0.21 vs 0.89 +/- 0.17, P = 0.001) after adjusting baseline characteristics (P < 0.001). In conclusion, the general health status of those with UA/NSTEMI was not good even after optimal PCI. In addition to angina-specific therapy, comprehensive supportive care would be needed to improve the general health status of acute coronary syndrome survivors.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. In : Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, editors. Braunwald's heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier;2012. p. 1178–1209.2. Bode C, Zirlik A. STEMI and NSTEMI: the dangerous brothers. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:1403–1404.3. Montalescot G, Dallongeville J, Van Belle E, Rouanet S, Baulac C, Degrandsart A, Vicaut E. OPERA Investigators. STEMI and NSTEMI: are they so different? 1 year outcomes in acute myocardial infarction as defined by the ESC/ACC definition (the OPERA registry). Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:1409–1417.4. Chan MY, Sun JL, Newby LK, Shaw LK, Lin M, Peterson ED, Califf RM, Kong DF, Roe MT. Long-term mortality of patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009; 119:3110–3117.5. García-García C, Subirana I, Sala J, Bruguera J, Sanz G, Valle V, Arós F, Fiol M, Molina L, Serra J, et al. Long-term prognosis of first myocardial infarction according to the electrocardiographic pattern (ST elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction and nonclassified myocardial infarction) and revascularization procedures. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108:1061–1067.6. Spertus JA, Jones P, McDonell M, Fan V, Fihn SD. Health status predicts long-term outcome in outpatients with coronary disease. Circulation. 2002; 106:43–49.7. Heidenreich PA, Spertus JA, Jones PG, Weintraub WS, Rumsfeld JS, Rathore SS, Peterson ED, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM, Havranek EP, et al. Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:752–756.8. Issa SM, Hoeks SE, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Van Gestel YR, Lenzen MJ, Verhagen HJ, Pedersen SS, Poldermans D. Health-related quality of life predicts long-term survival in patients with peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med. 2010; 15:163–169.9. Guyatt GH. Measurement of health-related quality of life in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993; 22:185A–191A.10. Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kolm P, Maron DJ, Zhang Z, Jurkovitz C, Zhang W, Hartigan PM, Lewis C, Veledar E, et al. Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:677–687.11. Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010; 8:13.12. Kim MJ, Jeon DS, Gwon HC, Kim SJ, Chang K, Kim HS, Tahk SJ. Korean MUSTANG Investigators. Current statin usage for patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: multicenter survey in Korea. Clin Cardiol. 2012; 35:700–706.13. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, Jneid H, Lincoff AM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011; 123:2022–2060.14. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, King SB 3rd, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE Jr, et al. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:2205–2241.15. King SB 3rd, Smith SC Jr, Hirshfeld JW Jr, Jacobs AK, Morrison DA, Williams DO, Feldman TE, Kern MJ, O'Neill WW, Schaff HV, et al. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: 2007 writing group to review new evidence and update the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention, writing on behalf of the 2005 writing committee. Circulation. 2008; 117:261–295.16. Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, Deyo RA, Prodzinski J, McDonell M, Fihn SD. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995; 25:333–341.17. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life: the EuroQol Group. Health Policy. 1990; 16:199–208.18. Wyrwich KW, Spertus JA, Kroenke K, Tierney WM, Babu AN, Wolinsky FD. Heart Disease Expert Panel. Clinically important differences in health status for patients with heart disease: an expert consensus panel report. Am Heart J. 2004; 147:615–622.19. Pecoits-Filho R, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. The malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome: the heart of the matter. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002; 17:28–31.20. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001; 33:337–343.21. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009; 119:e391–e479.22. Aune E, Røislien J, Mathisen M, Thelle DS, Otterstad JE. The "smoker's paradox" in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011; 9:97.23. Wakabayashi K, Romaguera R, Laynez-Carnicero A, Maluenda G, Ben-Dor I, Sardi G, Gaglia MA Jr, Mahmoudi M, Gonzalez MA, Delhaye C, et al. Impact of smoking on acute phase outcomes of myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2011; 22:217–222.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Coronary Artery Disease

- Sex Differences of the Clinical Characteristics and Early Management in the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry

- Consecutive Multivessel Myocardial Infarction during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Current Status of Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

- Comparison of the prognosis of patients with acute ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction