J Lipid Atheroscler.

2015 Dec;4(2):101-108. 10.12997/jla.2015.4.2.101.

Association Between Subjective Stress and Cardiovascular Diseases in Korean Population

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Nutritional Sciences and Food Management, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. yhmoon@ewha.ac.kr

- KMID: 2151817

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12997/jla.2015.4.2.101

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of subjective stress levels on various characteristics, dietary intake, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) among Korean people. METHOD: This study conducted analyses on subjective stress levels and demographic-, socioeconomic-, health-related factors, dietary intake and CVD of 15,474 subjects aged over 20 years from the 5th Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database. In addition, the presence of CVD including angina, myocardial infarction, and stroke was analyzed.

RESULTS

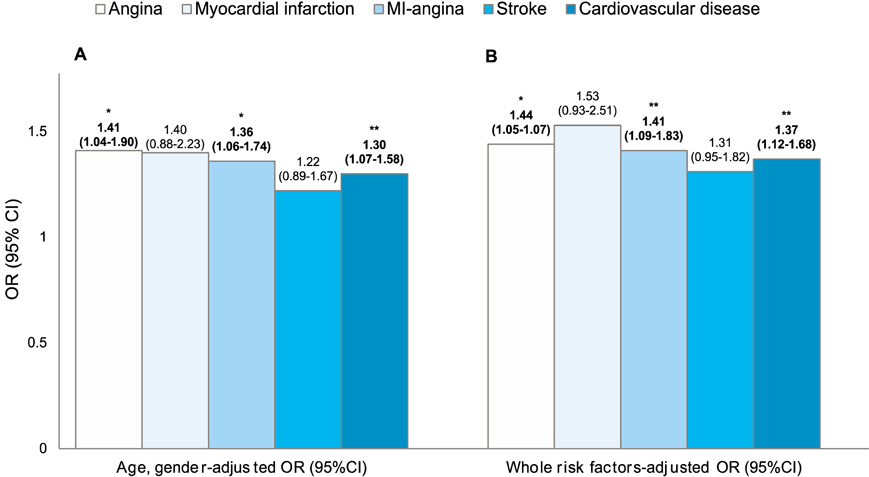

The responses of 25.6% of the subjects were that they felt high levels of stress. Significant differences in age, gender, education level, occupation, marital status, smoking and drinking status were observed by subjective stress levels (p<0.001 for all except p=0.035 for drinking status). After adjustment for non-modifiable covariates and modifiable covariates, subjects with high levels of stress showed an increase in the risk of angina, myocardial infarction-angina, and CVD, compared to those with low levels of stress [OR (95% CI) for non-modifiable covariates: 1.41 (1.04-1.90, p<0.05), 1.36 (1.06-174, p<0.05), and 1.30 (1.07-1.58, p<0.001)] and [OR (95% CI) for modifiable covariates: 1.44 (1.05-1.97, p<0.05), 1.41 (1.09-1.83, p<0.001), and 1.37 (1.12-1.68, p<0.001)]. Also, subjects with high levels of stress consumed more dietary fat than those with low levels of stress, but the opposite trend was observed regarding the consumption of carbohydrates (p<0.001 for both).

CONCLUSION

Our findings showed that subjective stress levels adjusted for modifiable risk factors induced increased occurrence of CVD than that adjusted for non-modifiable risk factors.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. De Vriendt T, Moreno LA, De Henauw S. Chronic stress and obesity in adolescents: scientific evidence and methodological issues for epidemiological research. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009; 19:511–519.

Article2. Lazarus RS. Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am Psychol. 1991; 46:352–367.

Article3. Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH. Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31:2383–2390.

Article4. Bergmann N, Gyntelberg F, Faber J. The appraisal of chronic stress and the development of the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Endocr Connect. 2014; 3:R55–R80.

Article5. Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009; 115:5349–5361.

Article6. Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012; 9:360–370.

Article7. Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update on current knowledge. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013; 34:337–354.

Article8. Pan A, Sun Q, Okereke OI, Rexrode KM, Hu FB. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA. 2011; 306:1241–1249.

Article9. Gullette EC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak M, Jiang W, Waugh RA, Frid DJ, et al. Effects of mental stress on myocardial ischemia during daily life. JAMA. 1997; 277:1521–1526.

Article10. Willich SN, Löwel H, Lewis M, Hörmann A, Arntz HR, Keil U. Weekly variation of acute myocardial infarction. Increased Monday risk in the working population. Circulation. 1994; 90:87–93.

Article11. Schwartz BG, French WJ, Mayeda GS, Burstein S, Economides C, Bhandari AK, et al. Emotional stressors trigger cardiovascular events. Int J Clin Pract. 2012; 66:631–639.

Article12. Statistics Korea. The cause of death statistics 2013 [Internet]. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr.13. World Heart Federation. Cardiovascular disease risk factors [Internet]. Available from: http://www.worldheart-federation.org.14. The fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (KNHANES V) [Internet]. Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr.15. Lee YJ, Choi GJ. The Effect of Korean Adult\'s Mental Health On QOL(Quality Of Life) -The Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2010. J Digit Converg. 2013; 11:321–327.16. Kogler L, Gur RC, Derntl B. Sex differences in cognitive regulation of psychosocial achievement stress: brain and behavior. Hum Brain Mapp. Forthcoming 2014.

Article17. Duchesne A, Pruessner JC. Association between subjective and cortisol stress response depends on the menstrual cycle phase. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013; 38:3155–3159.

Article18. Ignatyev Y, Assimov M, Dochshanov D, Ströhle A, Heinz A, Mundt AP. Social characteristics of psychological distress in a disadvantaged urban area of Kazakhstan. Community Ment Health J. 2014; 50:120–125.

Article19. Lazzarino AI, Yiengprugsawan V, Seubsman SA, Steptoe A, Sleigh AC. The associations between unhealthy behaviours, mental stress, and low socio-economic status in an international comparison of representative samples from Thailand and England. Global Health. 2014; 10:10.

Article20. Amlung M, MacKillop J. Understanding the effects of stress and alcohol cues on motivation for alcohol via behavioral economics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014; 38:1780–1789.

Article21. Evans BE, Greaves-Lord K, Euser AS, Tulen JH, Franken IH, Huizink AC. Alcohol and tobacco use and heart rate reactivity to a psychosocial stressor in an adolescent population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012; 126:296–303.

Article22. Becker HC. Effects of alcohol dependence and withdrawal on stress responsiveness and alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. 2012; 34:448–458.23. O'Connell H. Moderate alcohol use and mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 189:566–567.24. Warburton DM. Nicotine issues. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1992; 108:393–396.

Article25. Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006; 29:162–171.26. Arborelius L, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. J Endocrinol. 1999; 160:1–12.

Article27. Heinrichs SC, Cole BJ, Pich EM, Menzaghi F, Koob GF, Hauger RL. Endogenous corticotropin-releasing factor modulates feeding induced by neuropeptide Y or a tail-pinch stressor. Peptides. 1992; 13:879–884.

Article28. Takeda E, Terao J, Nakaya Y, Miyamoto K, Baba Y, Chuman H, et al. Stress control and human nutrition. J Med Invest. 2004; 51:139–145.

Article29. Newman E, O'Connor DB, Conner M. Daily hassles and eating behaviour: the role of cortisol reactivity status. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007; 32:125–132.

Article30. Nastaskin RS, Fiocco AJ. A survey of diet self-efficacy and food intake in students with high and low perceived stress. Nutr J. 2015; 14:42.

Article31. Barrington WE, Beresford SA, McGregor BA, White E. Perceived stress and eating behaviors by sex, obesity status, and stress vulnerability: findings from the vitamins and lifestyle (VITAL) study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014; 114:1791–1799.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Influence of Health-Related Perception on Depression among Adolescents: Focusing on the Mediating Effects of Stress

- Associations between Subjective Stress Level, Health-Related Habits, and Obesity according to Gender

- Association of Occupational Stress and Cardiorespiratory Fitness with Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Office Workers

- High Sodium Intake: Review of Recent Issues on Its Association with Cardiovascular Events and Measurement Methods

- Stress, Yangsaeng and Subjective Happiness Among Female Undergraduate Nursing Students in the Republic of Korea