Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2010 Oct;14(5):273-278. 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.5.273.

Effect of the Heat-exposure on Peripheral Sudomotor Activity Including the Density of Active Sweat Glands and Single Sweat Gland Output

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan 331-946, Korea. leejb@sch.ac.kr

- KMID: 2071693

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.5.273

Abstract

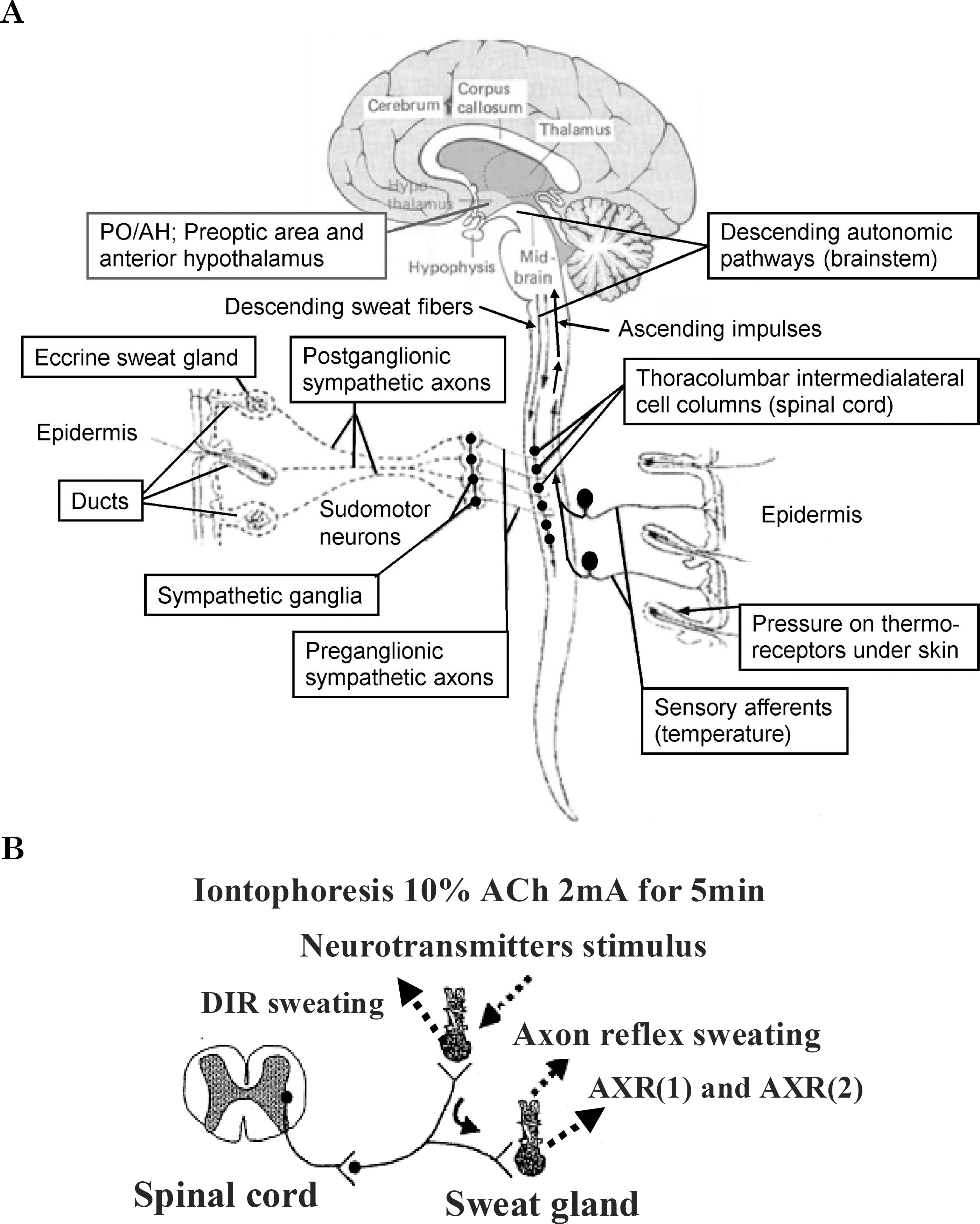

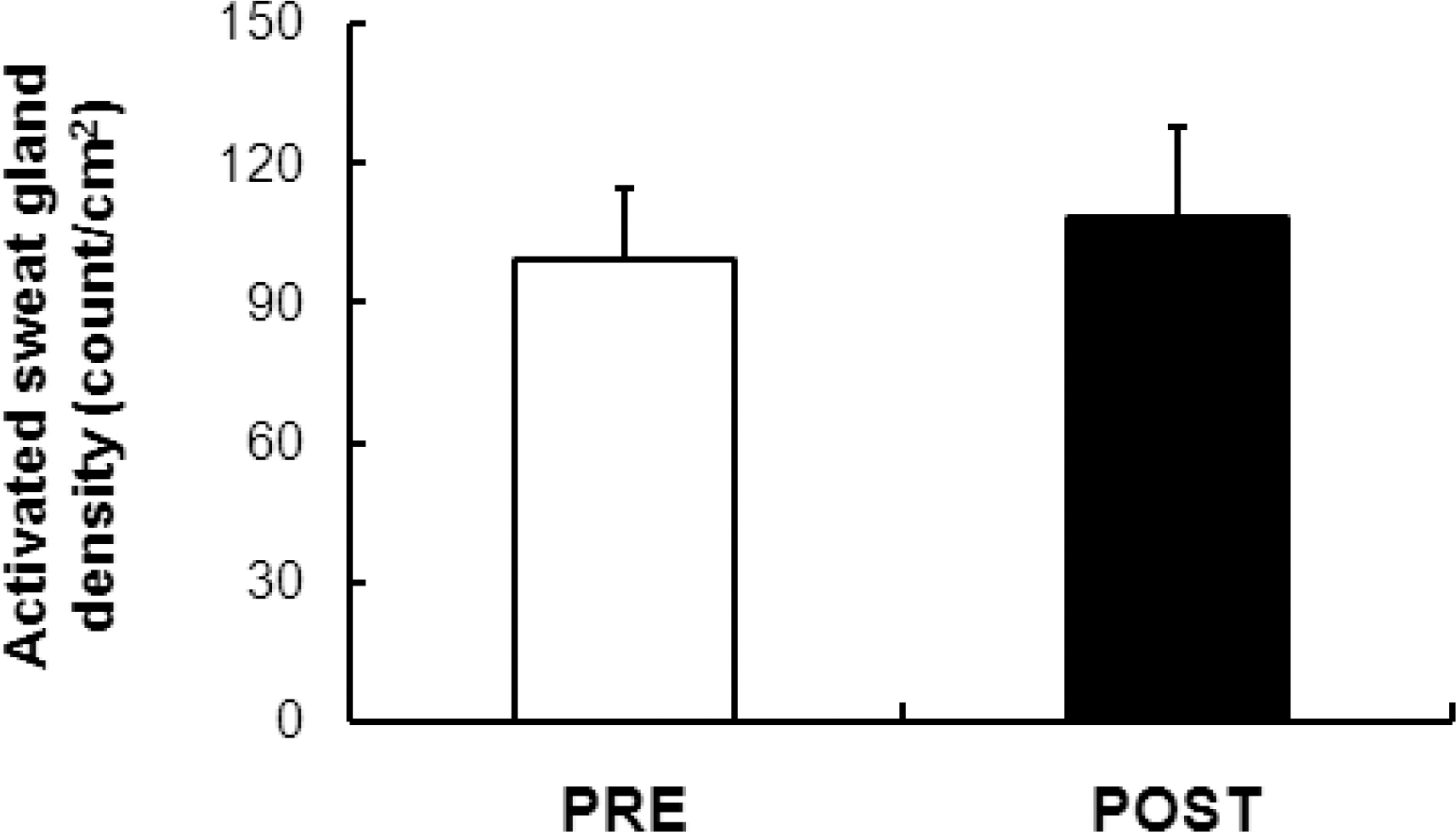

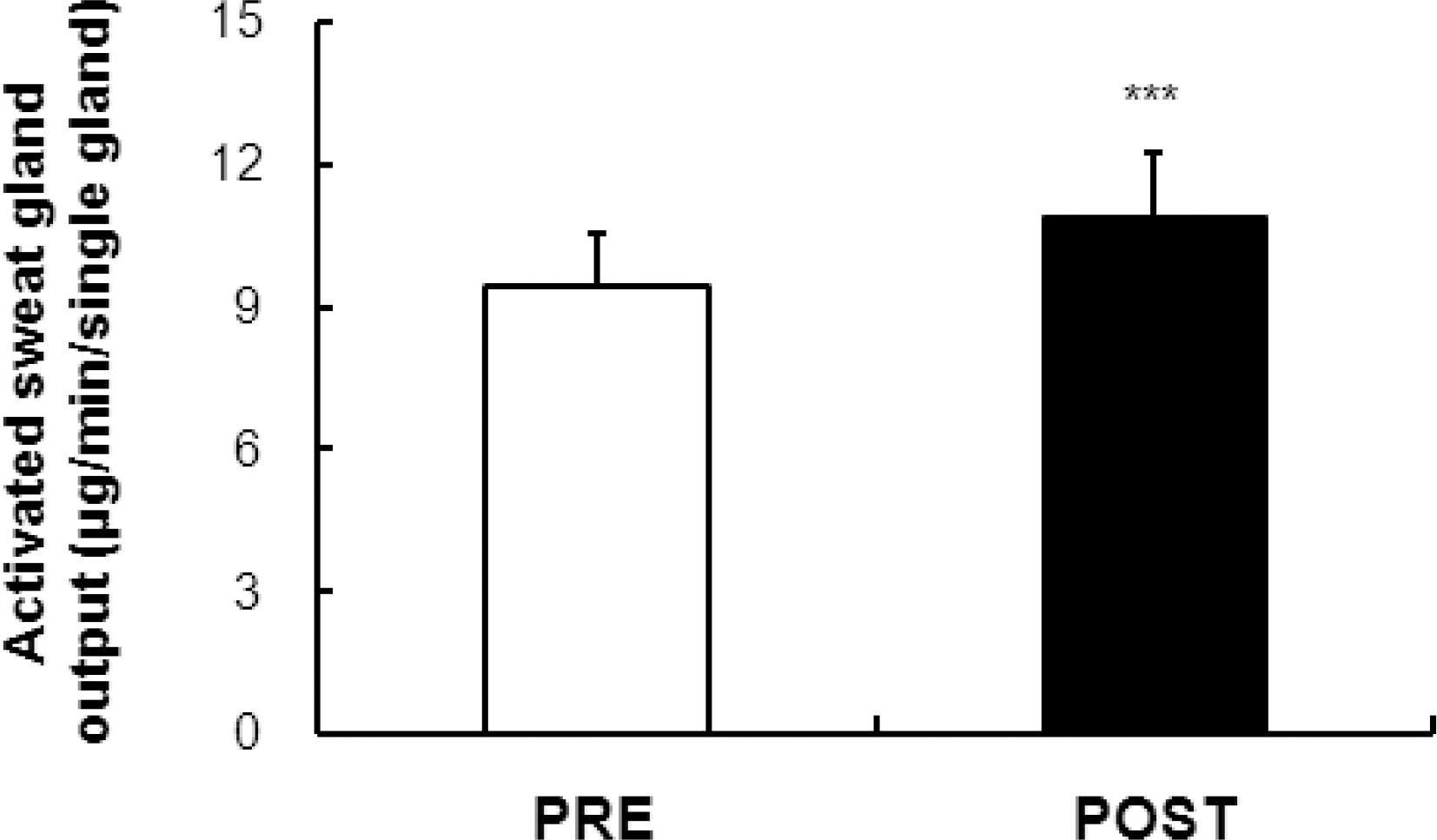

- Tropical inhabitants are able to tolerate heat through permanent residence in hot and often humid tropical climates. The goal of this study was to clarify the peripheral mechanisms involved in thermal sweating pre and post exposure (heat-acclimatization over 10 days) by studying the sweating responses to acetylcholine (ACh), a primary neurotransmitter of sudomotor activity, in healthy subjects (n=12). Ten percent ACh was administered on the inner forearm skin for iontophoresis. Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing, after iontophoresis (2 mA for 5 min) with ACH, was performed to determine directly activated (DIR) and axon reflex-mediated (AXR) sweating during ACh iontophoresis. The sweat rate, activated sweat gland density, sweat gland output per single gland activated, as well as oral and skin temperature changes were measured. The post exposure activity had a short onset time (p<0.01), higher active sweat rate [(AXR (p<0.001) and DIR (p<0.001)], higher sweat output per gland (p<0.001) and higher transepidermal water loss (p<0.001) compared to the pre-exposure measurements. The activated sweat rate in the sudomotor activity increased the output for post-exposure compared to the pre-exposure measurements. The results suggested that post-exposure activity showed a higher active sweat gland output due to the combination of a higher AXR (DIR) sweat rate and a shorter onset time. Therefore, higher sudomotor responses to ACh receptors indicate accelerated sympathetic nerve responsiveness to ACh sensitivity by exposure to environmental conditions.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Seasonal Acclimatization in Summer versus Winter to Changes in the Sweating Response during Passive Heating in Korean Young Adult Men

Jeong-Beom Lee, Tae-Wook Kim, Young-Ki Min, Hun-Mo Yang

Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;19(1):9-14. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2015.19.1.9.Seasonal acclimation in sudomotor function evaluated by QSART in healthy humans

Young Oh Shin, Jeong-Beom Lee, Jeong-Ho Kim

Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20(5):499-505. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.5.499.

Reference

-

References

1. Wilkerson WJ, Young RJ, Melius JM. Investigation of a fatal heat stroke. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1986; 47:A493–494.2. Nadel ER, Pandolf KB, Roberts MF, Stojwijk JA. Mechanisms of thermal acclimation to exercise and heat. J Appl Physiol. 1974; 37:515–520.

Article3. Kuno Y. Human Perspiration. Springfield: Charles C Thomas. 1956. 287–291.4. Vetrugno R, Liguori R, Cortelli P, Montagna P. Sympathetic skin response: basic mechanisms and clinical applications. Clin Auton Res. 2003; 13:256–270.5. Lee JB, Bae JS, Matsumoto T, Yang HM, Min YK. Tropical Malaysians and temperate Koreans exhibit significant differences in sweating sensitivity in response to iontophoretically administered acetylcholine. Int J Biometeorol. 2009; 53:149–157.

Article6. Bae JS, Lee JB, Matsumoto T, Timothy O, Min YK, Yang HM. Prolonged residence of temperate natives in the tropics produces a suppression of sweating. Pflugers Arch. 2006; 453:67–72.

Article7. Lee JB, Bae JS, Lee MY, Yang HM, Min YK, Song HY, Ko KK, Kwon JT, Matsumoto T. The change in peripheral sweating mechanisms of the tropical Malaysian who stays in Japan. J Therm Biol. 2004; 29:743–747.

Article8. Lee JB. Heat acclimatization in hot summer for ten weeks suppress the sensitivity of sweating in response to iontophoretically-administered acetylcholin. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008; 12:349–335.9. Illigens BM, Gibbons CH. Sweat testing to evaluate autonomic function. Clin Auton Res. 2009; 19:79–87.

Article10. Eishi K, Lee JB, Bae SJ, Takenaka M, Katayama I. Impaired Sweating Function in Adult Atopic Dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 147:683–688.11. Low PA. Laboratory evaluation of autonomic function. In Clinical Autonomic Disorders. 2nd ed.Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia;1997. p. 179–208.12. Low PA. Evaluation of sudomotor function. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004; 115:1506–1513.

Article13. Maeda A, Yamanouchi H, Lee JB, Katayama I. Oral prednisolone improved acetylcholine-induced sweating in Sjogen's syndrome related anhidrosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2000; 19:396–397.14. Wang Q, Aravinda KP, Lim EC, Chan YH, Deng C, Huang XF, Wilder-Smith EP. A static handgrip method for distal quantitative sweat measurements. Neuroscience Letters. 2007; 421:229–233.

Article15. Lee JB, Othman T, Lee JS, Quan FS, Choi JH, Yang HM, Min YK, Matsumoto T, Kosaka M. Sudomotor modifications by acclimatization of stay in temperate Japan of Malaysian native tropical subjects. Jan J Tropical Medicine Hygiene. 2002; 30:295–299.

Article16. Lee JB, Matsumoto T, Bea JS, Choi JH, Yang HM, Min YK. Economical Sweating Function in Africans: Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004; 8:21–25.17. Lee JB, Kosaka M, Othman T, Matsumoto T, Kaneda E, Yamauchi M, Taimura A, Ohwatari N, Nakase Y, Makita S. Evaluation of the applicability of infrared and thermistorthermometry in thermophysiology research. Trop Med. 1999; 41:133–142.18. Low PA, Caskey PE, Tuck RR, Fealey RD, Dyck PJ. Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test in normal and neuropathic subjects. Ann Neurol. 1983; 14:573–580.

Article19. Lee JB, Bae JS, Shin YO, Kang JC, Matsumoto T, Toktasynovna AA, Alipov Gabit K, Kim WJ, Min YK, Yang HM. Long-term tropical residency diminishes central sudomotor sensitivities in male subjects. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007; 11:233–237.20. Lee JB, Matsumoto T, Othman T, Kosaka M. Suppression of the sweat gland sensitivity to acetylcholine applied iontophoretically in tropical africans compared to temperate japanese. Trop Med. 1997; 39:111–121.21. Pinnagoda J, Tupker RA, Agner T, Serup J. Guidelines for transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurement. A report from the Standardization Group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990; 22:164–178.22. Lind AR, Bass DE. Optimal exposure time for development of acclimatization to heat. Fed Proc. 1963; 22:704–708.23. Hori S, Tanaka N. Adaptive change in physiological response of the men to heat induced by heat acclimatization and physical training. Jan J Tropical Medicine Hygiene. 1993; 21:193–199.24. Nielsen B, Strange S, Christensen NJ, Warberg J, Saltin B. Acute and adaptive responses in humans to exercise in a warm humid environment. Pflugers Arch. 1997; 434:49–56.

Article25. Pandolf BK. Time course of heat acclimation and its decay. Int J Sports Med. 1998; 19:S157–160.

Article26. Sawaka MN. Thermoregulatory responses to acute exercise heat stress and acclimation. Fregly MJ, Blatteis CM, editors. ed,. Handbook of Physiology, Section 4. Environmental Physiology. New York: Oxford University Press;1996. p. 157–185.27. Sugenoya J, Ogawa T, Jmai K, Ohnishi N, Natsume K. Cutaneous vasodilatation responses synchronize with sweat expulsions. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1995; 71:33–40.

Article28. Kenney WL, Munce TA. Aging and human temperature regulation. J Appl Physiol. 2003; 95:2598–2603.29. Scremin G, Kenney WL. Aging and the skin blood flow response to the unloading of baroreceptors during heat and cold stress. J Appl Physiol. 2004; 96:1019–1025.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- An Experimental Study on Sweat Secretion During 2 Hours of Heat Exposure

- Seasonal acclimation in sudomotor function evaluated by QSART in healthy humans

- Unilateral Frontal Hyperhidrosis

- Economical Sweating Function in Africans: Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test

- A case of apocrine sweat gland carcinoma in the scrotum