Yonsei Med J.

2015 Mar;56(2):368-374. 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.2.368.

Exponential Rise in Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) during Anti-Androgen Withdrawal Predicts PSA Flare after Docetaxel Chemotherapy in Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology and Urological Science Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. sjhong346@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2070012

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.2.368

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the relationship between rising patterns of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) before chemotherapy and PSA flare during the early phase of chemotherapy in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

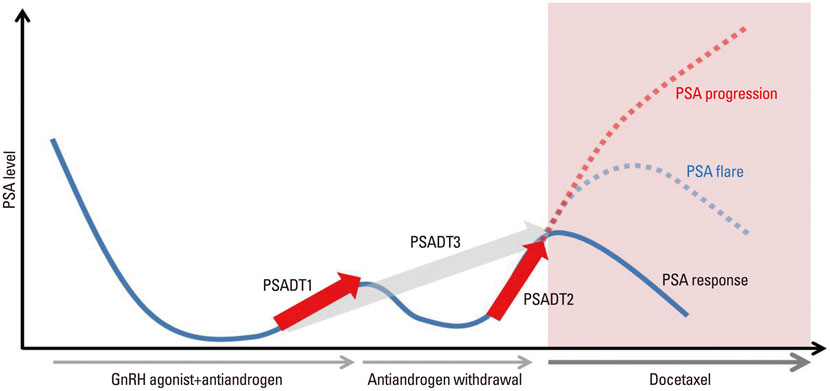

This study included 55 patients with CRPC who received chemotherapy and in whom pre-treatment or post-treatment PSA levels could be serially obtained. The baseline parameters included age, performance, Gleason score, PSA level, and disease extent. PSA doubling time was calculated using the different intervals: the conventional interval from the second hormone manipulation following the nadir until anti-androgen withdrawal (PSADT1), the interval from the initial rise after anti-androgen withdrawal to the start of chemotherapy (PSADT2), and the interval from the nadir until the start of chemotherapy (PSADT3). The PSA growth patterns were analyzed using the ratio of PSADT2 to PSADT1.

RESULTS

There were two growth patterns of PSA doubling time: 22 patients (40.0%) had a steady pattern with a more prolonged PSADT2 than PSADT1, while 33 (60.0%) had an accelerating pattern with a shorter PSADT2 than PSADT1. During three cycles of chemotherapy, PSA flare occurred in 11 patients (20.0%); of these patients, 3 were among 33 (9.1%) patients with an accelerating PSA growth pattern and 8 were among 22 patients (36.4%) with a steady PSA growth pattern (p=0.019). Multivariate analysis showed that only PSA growth pattern was an independent predictor of PSA flare (p=0.034).

CONCLUSION

An exponential rise in PSA during anti-androgen withdrawal is a significant predictor for PSA flare during chemotherapy in CRPC patients.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Aged

Aged, 80 and over

Androgen Antagonists

Antineoplastic Agents/*therapeutic use

Follow-Up Studies

Humans

Karnofsky Performance Status

Male

Middle Aged

Neoplasm Grading

Predictive Value of Tests

Prostate-Specific Antigen/*blood

Prostatic Neoplasms, Castration-Resistant/*blood/*drug therapy/pathology

Taxoids/*therapeutic use

Tumor Markers, Biological/blood

Androgen Antagonists

Antineoplastic Agents

Prostate-Specific Antigen

Taxoids

Tumor Markers, Biological

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Survival Outcomes of Concurrent Treatment with Docetaxel and Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer

Ho Seong Jang, Kyo Chul Koo, Kang Su Cho, Byung Ha Chung

Yonsei Med J. 2016;57(5):1070-1078. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1070.

Reference

-

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007; 57:43–66.

Article2. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005; 55:74–108.

Article3. Koo KC, Lee DH, Kim KH, Lee SH, Hong CH, Hong SJ, et al. Unrecognized kinetics of serum testosterone: impact on short-term androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2014; 55:570–575.

Article4. Kim YM, Park S, Kim J, Park S, Lee JH, Ryu DS, et al. Role of prostate volume in the early detection of prostate cancer in a cohort with slowly increasing prostate specific antigen. Yonsei Med J. 2013; 54:1202–1206.

Article5. Debes JD, Tindall DJ. Mechanisms of androgen-refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351:1488–1490.

Article6. Vaishampayan U, Hussain M. Update in systemic therapy of prostate cancer: improvement in quality and duration of life. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008; 8:269–281.

Article7. Joung JY, Jeong IG, Han KS, Kim TS, Yang SO, Seo HK, et al. Docetaxel chemotherapy of Korean patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: comparative analysis between 1st-line and 2nd-line docetaxel. Yonsei Med J. 2008; 49:775–782.

Article8. Hong SJ, Cho KS, Cho HY, Ahn H, Kim CS, Chung BH. A prospective, multicenter, open-label trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone refractory prostate cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2007; 48:1001–1008.

Article9. Armstrong AJ, Febbo PG. Using surrogate biomarkers to predict clinical benefit in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: an update and review of the literature. Oncologist. 2009; 14:816–827.

Article10. Tsui KH, Feng TH, Chung LC, Chao CH, Chang PL, Juang HH. Prostate specific antigen gene expression in androgen insensitive prostate carcinoma subculture cell line. Anticancer Res. 2008; 28:1969–1976.11. Thuret R, Massard C, Gross-Goupil M, Escudier B, Di Palma M, Bossi A, et al. The postchemotherapy PSA surge syndrome. Ann Oncol. 2008; 19:1308–1311.

Article12. Sella A, Sternberg CN, Skoneczna I, Kovel S. Prostate-specific antigen flare phenomenon with docetaxel-based chemotherapy in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008; 102:1607–1609.

Article13. Nelius T, Klatte T, de Riese W, Filleur S. Impact of PSA flare-up in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008; 40:97–104.

Article14. Fosså SD, Vaage S, Letocha H, Iversen J, Risberg T, Johannessen DC, et al. Liposomal doxorubicin (Caelyx) in symptomatic androgen-independent prostate cancer (AIPC)--delayed response and flare phenomenon should be considered. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2002; 36:34–39.

Article15. Heidenreich A, Sommer F, Ohlmann CH, Schrader AJ, Olbert P, Goecke J, et al. Prospective randomized Phase II trial of pegylated doxorubicin in the management of symptomatic hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004; 101:948–956.

Article16. Olbert PJ, Hegele A, Kraeuter P, Heidenreich A, Hofmann R, Schrader AJ. Clinical significance of a prostate-specific antigen flare phenomenon in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer receiving docetaxel. Anticancer Drugs. 2006; 17:993–996.

Article17. Arlen PM, Bianco F, Dahut WL, D'Amico A, Figg WD, Freedland SJ, et al. Prostate Specific Antigen Working Group guidelines on prostate specific antigen doubling time. J Urol. 2008; 179:2181–2185.

Article18. Daskivich TJ, Regan MM, Oh WK. Prostate specific antigen doubling time calculation: not as easy as 1, 2, 4. J Urol. 2006; 176:1927–1937.

Article19. Nelius T, Filleur S. PSA surge/flare-up in patients with castration-refractory prostate cancer during the initial phase of chemotherapy. Prostate. 2009; 69:1802–1807.

Article20. Tsui KH, Wu L, Chang PL, Hsieh ML, Juang HH. Identifying the combination of the transcriptional regulatory sequences on prostate specific antigen and human glandular kallikrein genes. J Urol. 2004; 172(5 Pt 1):2029–2034.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Long-Lasting Antiandrogen Withdrawal Syndrome in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Three Cases With Complete Response

- Efficacy of Alternative Antiandrogen Therapy for Prostate Cancer That Relapsed after Initial Maximum Androgen Blockade

- Dramatic Decline of PSA and Symptom Improvement after Estramustine Withdrawal in a Hormone-refractory Prostate Cancer Patient

- The Diagnostic Value of Prostate-specific Antigen and the of Routine Laboratory Examination for Early Detection

- Chemotherapy With Androgen Deprivation for Hormone-Naïve Prostate Cancer