Clin Endosc.

2014 Mar;47(2):162-173. 10.5946/ce.2014.47.2.162.

Predictive Factors for Intractability to Endoscopic Hemostasis in the Treatment of Bleeding Gastroduodenal Peptic Ulcers in Japanese Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology, Aichi Medical University School of Medicine, Aichi, Japan. nogasa@aichi-med-u.ac.jp

- KMID: 2049004

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2014.47.2.162

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/AIMS

Despite improvements in endoscopic hemostasis and pharmacological therapies, upper gastrointestinal (UGI) ulcers repeatedly bleed in 10% to 20% of patients, and those without early endoscopic reintervention or definitive surgery might be at a high risk for mortality. This study aimed to identify the risk factors for intractability to initial endoscopic hemostasis.

METHODS

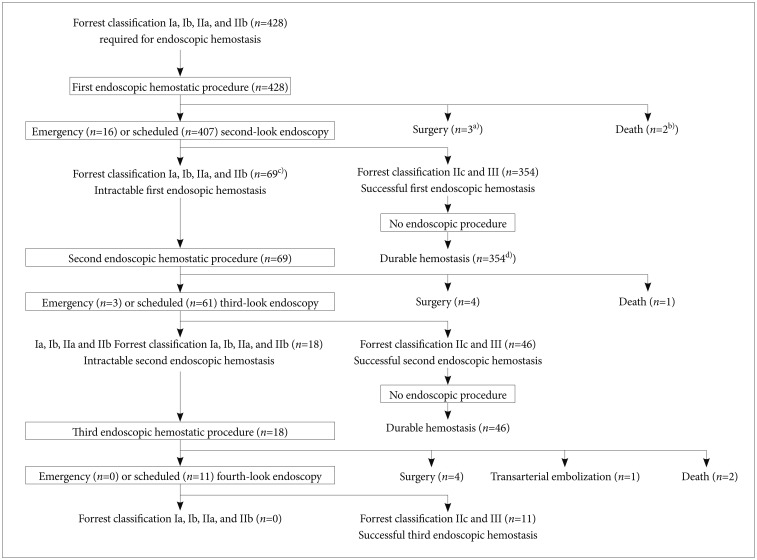

We analyzed intractability among 428 patients who underwent emergency endoscopy for bleeding UGI ulcers within 24 hours of arrival at the hospital.

RESULTS

Durable hemostasis was achieved in 354 patients by using initial endoscopic procedures. Sixty-nine patients with Forrest types Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb at the second-look endoscopy were considered intractable to the initial endoscopic hemostasis. Multivariate analysis indicated that age > or =70 years (odds ratio [OR], 2.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07 to 4.03), shock on admission (OR, 5.26; 95% CI, 2.43 to 11.6), hemoglobin <8.0 mg/dL (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.39 to 5.91), serum albumin <3.3 g/dL (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.89), exposed vessels with a diameter of > or =2 mm on the bottom of ulcers (OR, 4.38; 95% CI, 1.25 to 7.01), and Forrest type Ia and Ib (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.00) predicted intractable endoscopic hemostasis.

CONCLUSIONS

Various factors contribute to intractable endoscopic hemostasis. Careful observation after endoscopic hemostasis is important for patients at a high risk for incomplete hemostasis.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Predictive Factors for Endoscopic Hemostasis in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Il Kwun Chung

Clin Endosc. 2014;47(2):121-123. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.2.121.

Reference

-

1. Derry S, Loke YK. Risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage with long term use of aspirin: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2000; 321:1183–1187. PMID: 11073508.

Article2. Nakayama M, Iwakiri R, Hara M, et al. Low-dose aspirin is a prominent cause of bleeding ulcers in patients who underwent emergency endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2009; 44:912–918. PMID: 19436943.

Article3. Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Selection of patients for early discharge or outpatient care after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. Lancet. 1996; 347:1138–1140. PMID: 8609747.4. Barkun A, Sabbah S, Enns R, et al. The Canadian Registry on Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Endoscopy (RUGBE): Endoscopic hemostasis and proton pump inhibition are associated with improved outcomes in a real-life setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004; 99:1238–1246. PMID: 15233660.

Article5. Ramsoekh D, van Leerdam ME, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. Outcome of peptic ulcer bleeding, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005; 3:859–864. PMID: 16234022.6. Van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:1494–1499. PMID: 12873568.7. Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981; 27:80–93. PMID: 6971776.8. Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974; 2:394–397. PMID: 4136718.

Article9. Ikeda Y, Takakuwa R, Hatakeyama H, et al. Evaluation of endoscopic local injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine solution and surgical treatment on hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcer. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989; 90:1545–1547. PMID: 2586463.10. Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Prisco A, Garofano ML. Prospective comparison of argon plasma coagulator and heater probe in the endoscopic treatment of major peptic ulcer bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 48:191–195. PMID: 9717787.

Article11. Nishiaki M, Tada M, Yanai H, Tokiyama H, Nakamura H, Okita K. Endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding peptic ulcer using a hemostatic clip or pure ethanol injection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000; 47:1042–1044. PMID: 11020874.12. Hachisu T. Evaluation of endoscopic hemostasis using an improved clipping apparatus. Surg Endosc. 1988; 2:13–17. PMID: 3051463.13. Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996; 38:316–321. PMID: 8675081.

Article14. Elmunzer BJ, Young SD, Inadomi JM, Schoenfeld P, Laine L. Systematic review of the predictors of recurrent hemorrhage after endoscopic hemostatic therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008; 103:2625–2632. PMID: 18684171.

Article15. Urayama N, Shiraishi K, Aoyama K, et al. Factors predicting incomplete endoscopic hemostasis in bleeding gastroduodenal ulcers. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010; 57:519–523. PMID: 20698220.16. Jaramillo JL, Galvez C, Carmona C, Montero JL, Mino G. Prediction of further hemorrhage in bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:2135–2138. PMID: 7977228.17. Lin HJ, Wang K, Perng CL, Lee FY, Lee CH, Lee SD. Natural history of bleeding peptic ulcers with a tightly adherent blood clot: a prospective observation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996; 43:470–473. PMID: 8726760.

Article18. Cheng CL, Lin CH, Kuo CJ, et al. Predictors of rebleeding and mortality in patients with high-risk bleeding peptic ulcers. Dig Dis Sci. 2010; 55:2577–2583. PMID: 20094788.

Article19. De Abajo FJ, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with low-dose aspirin as plain and enteric-coated formulations. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2001; 1:1. PMID: 11228592.

Article20. Brullet E, Calvet X, Campo R, Rue M, Catot L, Donoso L. Factors predicting failure of endoscopic injection therapy in bleeding duodenal ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996; 43(2 Pt 1):111–116. PMID: 8635702.

Article21. Chung IK, Kim EJ, Lee MS, et al. Endoscopic factors predisposing to rebleeding following endoscopic hemostasis in bleeding peptic ulcers. Endoscopy. 2001; 33:969–975. PMID: 11668406.

Article22. Wong SK, Yu LM, Lau JY, et al. Prediction of therapeutic failure after adrenaline injection plus heater probe treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer. Gut. 2002; 50:322–325. PMID: 11839708.

Article23. Eriksson LG, Ljungdahl M, Sundbom M, Nyman R. Transcatheter arterial embolization versus surgery in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008; 19:1413–1418. PMID: 18755604.

Article24. Ripoll C, Banares R, Beceiro I, et al. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004; 15:447–450. PMID: 15126653.

Article25. Venclauskas L, Bratlie SO, Zachrisson K, Maleckas A, Pundzius J, Jonson C. Is transcatheter arterial embolization a safer alternative than surgery when endoscopic therapy fails in bleeding duodenal ulcer? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010; 45:299–304. PMID: 20017710.

Article26. Wong TC, Wong KT, Chiu PW, et al. A comparison of angiographic embolization with surgery after failed endoscopic hemostasis to bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 73:900–908. PMID: 21288512.

Article27. Larssen L, Moger T, Bjornbeth BA, Lygren I, Klow NE. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of bleeding duodenal ulcers: a 5.5-year retrospective study of treatment and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008; 43:217–222. PMID: 18224566.

Article28. Ljungdahl M, Eriksson LG, Nyman R, Gustavsson S. Arterial embolisation in management of massive bleeding from gastric and duodenal ulcers. Eur J Surg. 2002; 168:384–390. PMID: 12463427.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Endoscopic Management of Peptic Ulcer Bleeding: Recent Advances

- Endoscopic Hemostatic Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Bleeding

- Recent Developments in the Endoscopic Treatment of Patients with Peptic Ulcer Bleeding

- Factors Predicting the Failure of Repeated Endoscopic Treatment in Patients with peptic Ulcer Bleeding

- Endoscopic Alcohol Injection Therapy in Bleeding Peptic Ulcers