Restor Dent Endod.

2013 May;38(2):59-64. 10.5395/rde.2013.38.2.59.

Does apical root resection in endodontic microsurgery jeopardize the prosthodontic prognosis?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Microscope Center, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Oral Science Research Center, Yonsei University College of Dentistry, Seoul, Korea. andyendo@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 1995460

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2013.38.2.59

Abstract

- Apical surgery cuts off the apical root and the crown-to-root ratio becomes unfavorable. Crown-to-root ratio has been applied to periodontally compromised teeth. Apical root resection is a different matter from periodontal bone loss. The purpose of this paper is to review the validity of crown-to-root ratio in the apically resected teeth. Most roots have conical shape and the root surface area of coronal part is wider than apical part of the same length. Therefore loss of alveolar bone support from apical resection is much less than its linear length.The maximum stress from mastication concentrates on the cervical area and the minimum stress was found on the apical 1/3 area. Therefore apical root resection is not so harmful as periodontal bone loss. Osteotomy for apical resection reduces longitudinal width of the buccal bone and increases the risk of endo-perio communication which leads to failure. Endodontic microsurgery is able to realize 0 degree or shallow bevel and precise length of root resection, and minimize the longitudinal width of osteotomy. The crown-to-root ratio is not valid in evaluating the prosthodontic prognosis of the apically resected teeth. Accurate execution of endodontic microsurgery to preserve the buccal bone is essential to avoid endo-perio communication.

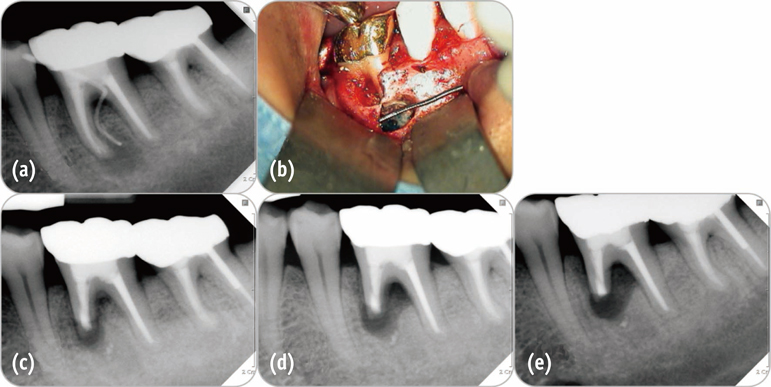

Figure

Reference

-

1. Reynolds JM. Abutment selection for fixed prosthodontics. J Prosthet Dent. 1968; 19:483–488.

Article2. Nyman SR, Lang NP. Tooth mobility and the biological rationale for splinting teeth. Periodontol 2000. 1994; 4:15–22.

Article3. Nyman S, Lindhe J, Lundgren D. The role of occlusion for the stability of fixed bridges in patients with reduced periodontal tissue support. J Clin Periodontol. 1975; 2:53–66.

Article4. Sorensen JA, Martinoff JT. Endodontically treated teeth as abutments. J Prosthet Dent. 1985; 53:631–636.

Article5. Goodacre CJ, Spolnik KJ. The prosthodontic management of endodontically treated teeth: a literature review. Part I. Success and failure data, treatment concepts. J Prosthodont. 1994; 3:243–250.

Article6. Shillingburg HT. Fundamentals of fixed prosthodontics. 3rd ed. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co.;1997.7. Rosenstiel SF, Land MF, Fujimoto J. Contemporary fixed prosthodontics. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier;2006.8. Johnston JF, Dykema RW, Goodacre CJ, Phillips RW. Johnston's Modern practice in fixed prosthodontics. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;1986.9. Carr AB, McGivney GP, Brown DT. McCracken's removable partial prosthodontics. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier;2005.10. Penny RE, Kraal JH. Crown-to-root ratio: its significance in restorative dentistry. J Prosthet Dent. 1979; 42:34–38.

Article11. McGuire MK. Prognosis versus actual outcome: a long-term survey of 100 treated periodontal patients under maintenance care. J Periodontol. 1991; 62:51–58.

Article12. McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. III. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in accurately predicting tooth survival. J Periodontol. 1996; 67:666–674.

Article13. Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. Prevalence of Periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012; 91:914–920.

Article14. Grossmann Y, Sadan A. The prosthodontic concept of crown-to-root ratio: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 2005; 93:559–562.

Article15. Kim E, Song JS, Jung IY, Lee SJ, Kim S. Prospective clinical study evaluating endodontic microsurgery outcomes for cases with lesions of endodontic origin compared with cases with lesions of combined periodontal-endodontic origin. J Endod. 2008; 34:546–551.

Article16. Setzer FC, Shah SB, Kohli MR, Karabucak B, Kim S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature-part 1: Comparison of traditional root-end surgery and endodontic microsurgery. J Endod. 2010; 36:1757–1765.

Article17. Jepsen A. Root surface measurement and a method for x-ray determination of root surface area. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963; 21:35–46.

Article18. Ante IH. The fundamental principles of abutments. Bull Mich State Dent Soc. 1926; 8:232–257.19. Leempoel PJ, Käyser AF, Van Rossum GM, De Haan AF. The survival rate of bridges. A study of 1674 bridges in 40 Dutch general practices. J Oral Rehabil. 1995; 22:327–330.

Article20. Fayyad MA, Al-Rafee MA. Failure of dental bridges. IV. Effect of supporting periodontal ligament. J Oral Rehabil. 1997; 24:401–403.

Article21. Levy AR, Wright WH. The relationship between attachment height and attachment area of teeth using a digitizer and a digital computer. J Periodontol. 1978; 49:483–485.

Article22. Hermann DW, Gher ME Jr, Dunlap RM, Pelleu GB Jr. The potential attachment area of the maxillary first molar. J Periodontol. 1983; 54:431–434.

Article23. Dejak B, Mlotkowski A, Romanowicz M. Finite element analysis of stresses in molars during clenching and mastication. J Prosthet Dent. 2003; 90:591–597.

Article24. Anitua E, Tapia R, Luzuriaga F, Orive G. Influence of implant length, diameter, and geometry on stress distribution: a finite element analysis. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2010; 30:89–95.25. Himmlová L, Dostálová T, Kácovský A, Konvicková S. Influence of implant length and diameter on stress distribution: a finite element analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2004; 91:20–25.

Article26. Cvek M, Tsilingaridis G, Andreasen JO. Survival of 534 incisors after intra-alveolar root fracture in patients aged 7-17 years. Dent Traumatol. 2008; 24:379–387.

Article27. Remington DN, Joondeph DR, Artun J, Riedel RA, Chapko MK. Long-term evaluation of root resorption occurring during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989; 96:43–46.

Article28. Kalkwarf KL, Krejci RF, Pao YC. Effect of apical root resorption on periodontal support. J Prosthet Dent. 1986; 56:317–319.

Article29. Kim E, Fallahrastegar A, Hur YY, Jung IY, Kim S, Lee SJ. Difference in root canal length between Asians and Caucasians. Int Endod J. 2005; 38:149–151.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Prognosis of the Apical Fragment of Root Fractures after Root Canal Treatment of Both Fragments in Immature Permanent Teeth

- Success and failure of endodontic microsurgery

- Endodontic treatment of a C-shaped mandibular second premolar with four root canals and three apical foramina: a case report

- The application of “bone window technique” using piezoelectric saws and a CAD/CAM-guided surgical stent in endodontic microsurgery on a mandibular molar case

- Effects of the endodontic access cavity on apical debris extrusion during root canal preparation using different single-file systems