J Korean Med Assoc.

2015 Feb;58(2):93-99. 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.2.93.

Concept and importance of patient identification for patient safety

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medcine, Seoul, Korea. hohouno@naver.com

- KMID: 1958369

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2015.58.2.93

Abstract

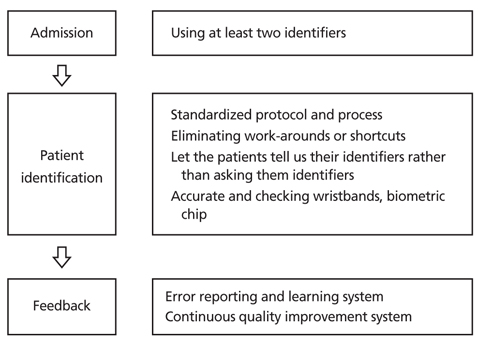

- Patient identification (PI) errors have been one of the most serious global healthcare quality issues for patient safety. Errors in PI are the root causes of many adverse events. Patient identification is the very first International Patient Safety Goal; however the current healthcare system is not culturally or structurally organized for preventing PI errors. The general procedures for the prevention of PI errors include using at least two identifiers, checking of accurate wristbands, standardizing the PI process, and eliminating shortcuts. Standardized protocols such as a good surgical site mark, a surgical checklist, the mandatory 'time-out', and the rule of the five rights for safe medication should be applied. For example, the surgical checklists have significantly improved mortality and decreased complications from surgery. During patient interactions, patients should be treated as partners in efforts to prevent all avoidable harm in healthcare. For example, patients should state their identifiers rather than be asked to confirm their identifiers. All healthcare professionals should receive training in patient safety concepts and strategies to enhance patient participation. For the future prevention of PI errors, patient photographs on wristbands, barcodes, biometric markers, fingerprints, retina scans, radiofrequency identification chips, and framework checklists for identifying a range of clinical care processes will ideally be available to healthcare professionals for improving patient safety and clinical outcomes. The changes are sometimes not pleasant but if we have to accept the changes, the changes should be started from me for the safety of everyone and every time in all healthcare services.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Approaches to improve patient safety in healthcare organizations

Sang-Il Lee

J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58(2):90-92. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.2.90.

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Patient safety checklists [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2015. cited 2015 Jan 12. Available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/checklists/en/.2. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press;2000.3. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. PATH (performance assessment tool for quality improvement in hospitals) project; 2010 [Internet]. Copenhagen: World Health Organization;2010. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/countries/croatia/news/news/2010/02/path-performance-assessment-tool-for-quality-improvement-in-hospitals-project.4. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority. Pennsylvania patient safety authority issues annual report for 2013 [Internet]. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority;2014. cited 2015 Jan 12. Available from: http://patientsafetyauthority.org/NewsAndInformation/PressReleases/2014/Pages/pr_April_30_2014.aspx.5. Government of South Australia. Policies, standards and guide-lines. Adelaide: Government of South Australia;cited 2015 Jan 12. Available from: http://dpc.sa.gov.au/policies-standards-and-guidelines.6. Seferian EG, Jamal S, Clark K, Cirricione M, Burnes-Bolton L, Amin M, Romanoff N, Klapper E. A multidisciplinary, multi-faceted improvement initiative to eliminate mislabelled laboratory specimens at a large tertiary care hospital. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014; 23:690–697.

Article7. Pamela B. A multi-observer study of the effect of including point-of-care patient photographs with portable radiography: a means to reduce wrong-patient errors [dissertation]. Atlanta: Emory University;2013.8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient surgery [Internet]. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;cited 2015 Jan 12. Available from: http://psnet.ahrq.gov/collectionBrowse.aspx?taxonomyID=443.9. The Joint Commission. Improving patient and worker safety: opportunities for synergy, collaboration and innovation [Inter-net]. Oakbrook Terrace: The Joint Commission;2012. cited 2015 Jan 28. Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/TJC-ImprovingPatientAndWorkerSafety-Monograph.pdf.10. Zeeshan MF, Dembe AE, Seiber EE, Lu B. Incidence of adverse events in an integrated US healthcare system: a retrospective observational study of 82,784 surgical hospitalizations. Patient Saf Surg. 2014; 8:23.

Article11. Bittle MJ, Charache P, Wassilchalk DM. Registration-associated patient misidentification in an academic medical center: causes and corrections. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007; 33:25–33.

Article12. Wright AA, Katz IT. Bar coding for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:329–331.

Article13. Seiden SC, Barach P. Wrong-side/wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient adverse events: are they preventable? Arch Surg. 2006; 141:931–939.

Article14. Tarpey K, Schaaf E, Lakhani U, Balcitis J. A proactive risk avoidance system using failure mode and effects analysis for "same-name" physician orders. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010; 36:461–467.

Article15. Salinas M, Lopez-Garrigos M, Lillo R, Gutierrez M, Lugo J, Leiva-Salinas C. Patient identification errors: the detective in the laboratory. Clin Biochem. 2013; 46:1767–1769.

Article16. Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, Joseph S, Kibatala PL, Lapitan MC, Merry AF, Moorthy K, Reznick RK, Taylor B, Gawande AA. Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:491–499.

Article17. Tridandapani S, Ramamurthy S, Provenzale J, Obuchowski NA, Evanoff MG, Bhatti P. A multiobserver study of the effects of including point-of-care patient photographs with portable radio-graphy: a means to detect wrong-patient errors. Acad Radiol. 2014; 21:1038–1047.

Article18. Mazor KM, Simon SR, Gurwitz JH. Communicating with patients about medical errors: a review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:1690–1697.20. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press;2001.21. Stahel PF, Sabel AL, Victoroff MS, Varnell J, Lembitz A, Boyle DJ, Clarke TJ, Smith WR, Mehler PS. Wrong-site and wrong-patient procedures in the universal protocol era: analysis of a prospective database of physician self-reported occurrences. Arch Surg. 2010; 145:978–984.

Article22. Ring DC, Herndon JH, Meyer GS. Case records of The Massachusetts General Hospital: case 34-2010: a 65-year-old woman with an incorrect operation on the left hand. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:1950–1957.23. Chassin MR, Becher EC. The wrong patient. Ann Intern Med. 2002; 136:826–833.

Article24. College of American Pathologists. Valenstein PN, Raab SS, Walsh MK. Identification errors involving clinical laboratories: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of patient and specimen identification errors at 120 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006; 130:1106–1113.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effects of Nurses' Patient Safety Management Importance, Patient Safety Culture and Nursing Service Quality on Patient Safety Management Activities in Tertiary Hospitals

- Concept Analysis of Patient Rights

- Concept Analysis of Patient Safety

- An Importance-Performance Analysis of patient safety activities for inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals

- Patient Safety Perception of Nurses as related to Patient Safety Management Performance in Tertiary Hospitals