Korean Circ J.

2013 Oct;43(10):664-673. 10.4070/kcj.2013.43.10.664.

The Impact of Ischemic Time on the Predictive Value of High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Treated by Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Gwangju Veterans Hospital, Gwangju, Korea. kvhwkim@chol.com

- 2Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Chonnam National College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea.

- KMID: 1826557

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2013.43.10.664

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

The high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), a marker of inflammation, has been known to be elevated in patients with coronary artery disease. However, there is controversy about the predictive value of hs-CRP after acute myocardial infarction (MI). Therefore, we evaluated the impact of ischemic time on the predictive value of hs-CRP in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients who were treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

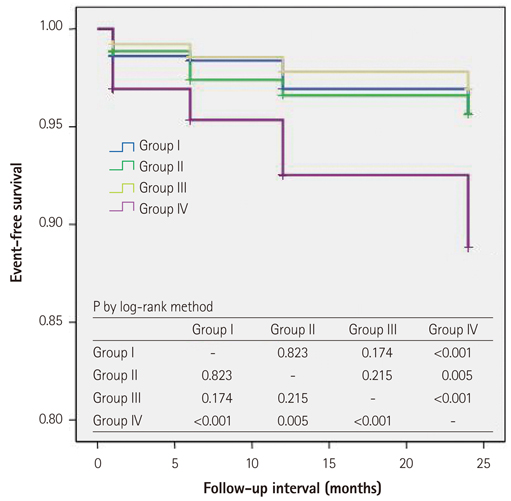

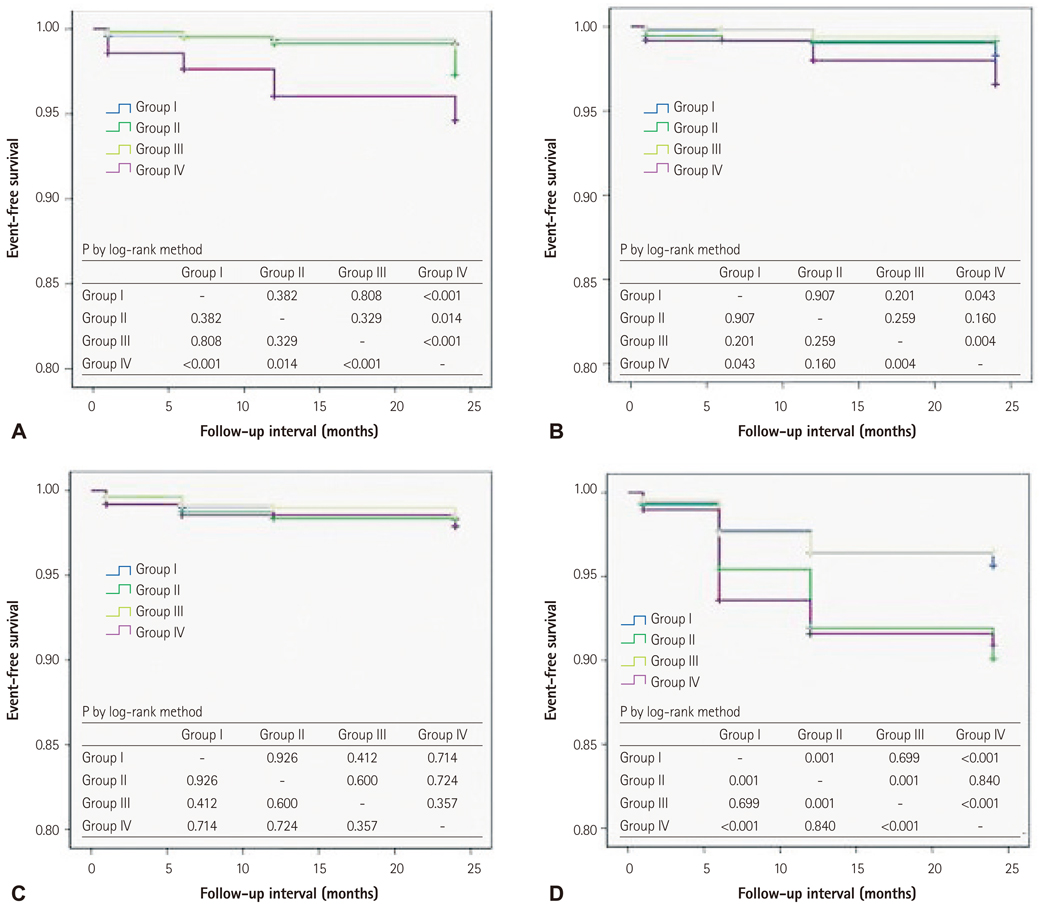

We enrolled 5123 STEMI patients treated by primary PCI from the Korean Working Group in Myocardial Infarction and divided enrolled patients into four groups by symptom-to-balloon time (SBT) and level of hs-CRP (Group I: SBT <6 hours and hs-CRP <3 mg/L, Group II: SBT <6 hours and hs-CRP > or =3 mg/L, Group III: SBT > or =6 hours and hs-CRP <3 mg/L, and Group IV: SBT > or =6 hours and hs-CRP > or =3 mg/L). To evaluate the impact of ischemic time on the predictive value of hs-CRP in STEMI patients, we compared the cumulative cardiac event-free survival rate between these four groups.

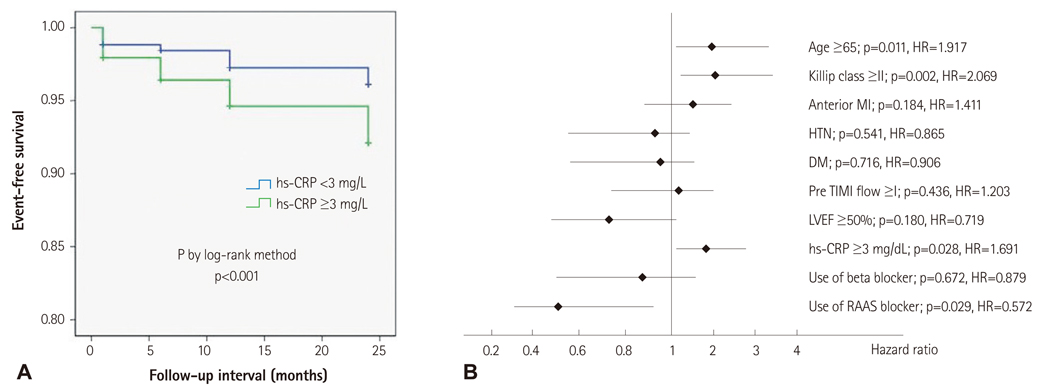

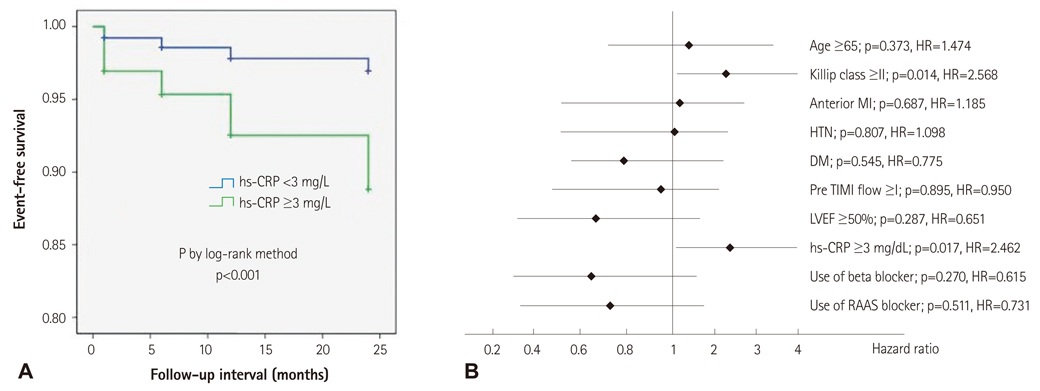

RESULTS

The sum of the cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality and recurrence of MI was higher in Group IV than in the other groups. However, there was no significant difference among Group I, Group II, and Group III. The Cox-regression analyses showed that an elevated level of hs-CRP (> or =3 mg/L) was an independent predictor of long-term cardiovascular outcomes only among late-presenting STEMI patients (p=0.017, hazard ratio=2.462).

CONCLUSION

For STEMI patients with a long ischemic time (> or =6 hours), an elevated level of hs-CRP is a poor prognostic factor of long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Therapeutic Hypothermia for Cardioprotection in Acute Myocardial Infarction

In Sook Kang, Ikeno Fumiaki, Wook Bum Pyun

Yonsei Med J. 2016;57(2):291-297. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.2.291.

Reference

-

1. Roberts WL, Moulton L, Law TC, et al. Evaluation of nine automated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein methods: implications for clinical and epidemiological applications. Part 2. Clin Chem. 2001; 47:418–425.2. Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003; 107:499–511.3. Zacho J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen JS, Grande P, Sillesen H, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated C-reactive protein and ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1897–1908.4. Zebrack JS, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, Anderson JL. Intermountain Heart Collaboration Study Group. C-reactive protein and angiographic coronary artery disease: independent and additive predictors of risk in subjects with angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 39:632–637.5. Bogaty P, Poirier P, Simard S, Boyer L, Solymoss S, Dagenais GR. Biological profiles in subjects with recurrent acute coronary events compared with subjects with long-standing stable angina. Circulation. 2001; 103:3062–3068.6. Haverkate F, Thompson SG, Pyke SD, Gallimore JR, Pepys MB. European Concerted Action on Thrombosis and Disabili ties Angina Pectoris Study Group. Production of C-reactive protein and risk of coronary events in stable and unstable angina. Lancet. 1997; 349:462–466.7. Tomoda H, Aoki N. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein levels within six hours after the onset of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2000; 140:324–328.8. Thompson SG, Kienast J, Pyke SD, Haverkate F, van de Loo JC. European Concerted Action on Thrombosis and Disabilities Angina Pectoris Study Group. Hemostatic factors and the risk of myocardial infarction or sudden death in patients with angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:635–641.9. Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Jablonski KA, et al. Prognostic significance of the Centers for Disease Control/American Heart Association high-sensitivity C-reactive protein cut points for cardiovascular and other outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007; 115:1528–1536.10. Mega JL, Morrow DA, De Lemos JA, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide at presentation and prognosis in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: an ENTIRE-TIMI-23 substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:335–339.11. Nikfardjam M, Müllner M, Schreiber W, et al. The association between C-reactive protein on admission and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Intern Med. 2000; 247:341–345.12. Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2010; 122:2748–2764.13. Berk BC, Weintraub WS, Alexander RW. Elevation of C-reactive protein in "active" coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990; 65:168–172.14. Tomoda H, Aoki N. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein levels within six hours after the onset of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2000; 140:324–328.15. Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Gallimore JR, et al. The prognostic value of C-reactive protein and serum amyloid a protein in severe unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:417–424.16. Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Gallimore JR, et al. Enhanced inflammatory response in patients with preinfarction unstable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 34:1696–1703.17. Hong YJ, Jeong MH, Choi YH, et al. Relation between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and coronary plaque components in patients with acute coronary syndrome: virtual histology-intravascular ultrasound analysis. Korean Circ J. 2011; 41:440–446.18. Lagrand WK, Niessen HW, Wolbink GJ, et al. C-reactive protein colocalizes with complement in human hearts during acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997; 95:97–103.19. Griselli M, Herbert J, Hutchinson WL, et al. C-reactive protein and complement are important mediators of tissue damage in acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 1999; 190:1733–1740.20. Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM, Tennent GA, et al. Targeting C-reactive protein for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006; 440:1217–1221.21. Ahmed K, Jeong MH, Chakraborty R, et al. Prognostic impact of baseline high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention based on body mass index. Korean Circ J. 2012; 42:164–172.22. Vrsalovic M, Pintaric H, Babic Z, et al. Impact of admission anemia, C-reactive protein and mean platelet volume on short term mortality in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty. Clin Biochem. 2012; 45:1506–1509.23. Mouridsen MR, Intzilakis T, Binici Z, Nielsen OW, Sajadieh A. Prognostic value of high sensitive C-reactive protein in subjects with silent myocardial ischemia. J Electrocardiol. 2012; 45:260–264.24. Raposeiras-Roubín S, Barreiro Pardal C, Rodiño Janeiro B, Abu-Assi E, García-Acuña JM, González-Juanatey JR. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is a predictor of in-hospital cardiac events in acute myocardial infarction independently of GRACE risk score. Angiology. 2012; 63:30–34.25. Schoos MM, Kelbæk H, Kofoed KF, et al. Usefulness of preprocedure high-sensitivity C-reactive protein to predict death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and stent thrombosis according to stent type in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction randomized to bare metal or drug-eluting stenting during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 107:1597–1603.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Current Status of Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

- Missing Right Coronary Artery in a Patient with Acute Inferior ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Case of Extremely Rare Variation of Coronary Anatomy

- Consecutive Multivessel Myocardial Infarction during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- A Case of Coronary Artery Dissection after Blunt Chest Trauma Resulting in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

- Combined Assessments of Biochemical Markers and ST-Segment Resolution Provide Additional Prognostic Information for Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction