Korean Circ J.

2012 Feb;42(2):129-132. 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.2.129.

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia in a Patient With Recurrent Exertional Syncope

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. choyk@mail.knu.ac.kr

- KMID: 1826387

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2012.42.2.129

Abstract

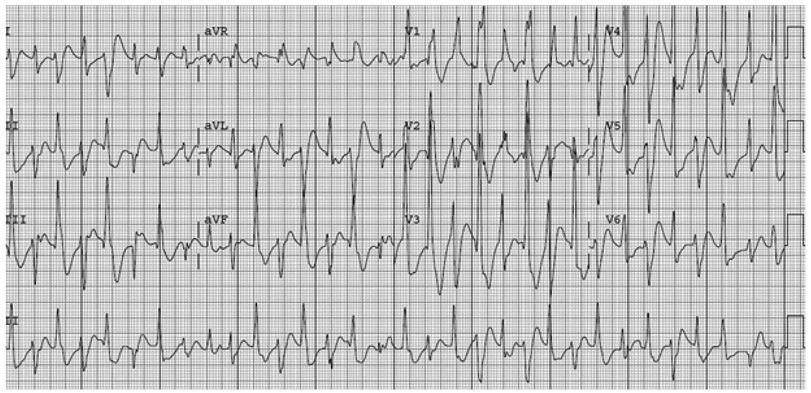

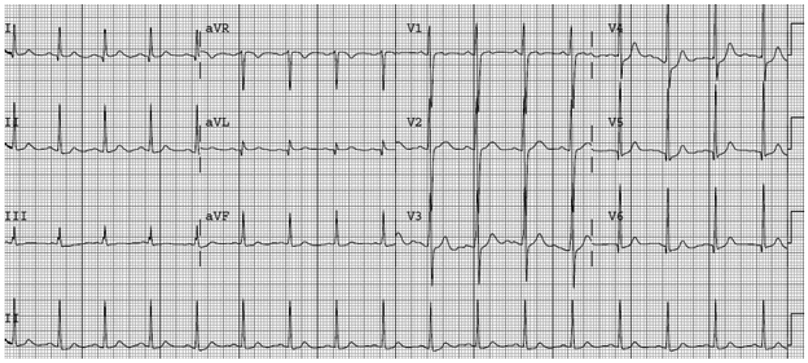

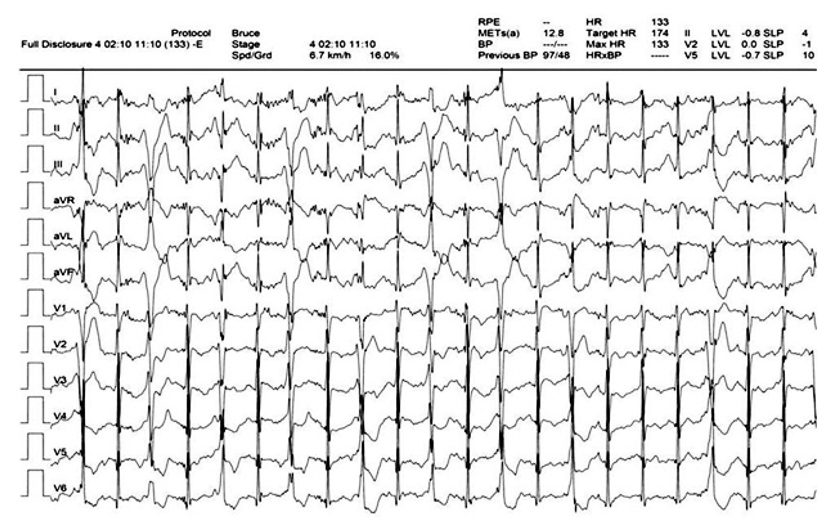

- A 16-year-old male with a prior history of recurrent syncope was referred to our hospital after being resuscitated from cardiac arrest developed while playing volleyball. His electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated ventricular fibrillation at a local emergency department. After referral, an ECG showed bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (VT) and nonsustained Torsade de Pointes. Two days later, his heart rate became regular, and no additional episodes of VT were observed. His ECG showed sinus rhythm with a corrected QT interval of 423 msec, and two-dimensional echocardiography was unremarkable. We made the diagnosis of a catecholaminergic polymorphic VT. However, only premature ventricular complex bigeminy was induced on exercise ECG and epinephrine infusion tests, and the patient showed no episodes of syncope. His father and mother had different missense mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor on genetic testing. The proband had both mutations in different alleles and was symptomatic. It was recommended that the patient avoid competitive physical activities, and a beta-blocker was prescribed.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adolescent

Alleles

Catecholamines

Echocardiography

Electrocardiography

Emergencies

Epinephrine

Fathers

Genetic Testing

Heart Arrest

Heart Rate

Humans

Male

Mothers

Motor Activity

Mutation, Missense

Referral and Consultation

Ryanodine Receptor Calcium Release Channel

Syncope

Tachycardia

Tachycardia, Ventricular

Torsades de Pointes

Ventricular Fibrillation

Ventricular Premature Complexes

Volleyball

Catecholamines

Epinephrine

Ryanodine Receptor Calcium Release Channel

Tachycardia

Tachycardia, Ventricular

Figure

Reference

-

1. Horner JM, Ackerman MJ. Ventricular ectopy during treadmill exercise stress testing in the evaluation of long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008. 5:1690–1694.2. Krahn AD, Healey JS, Chauhan V, et al. Systematic assessment of patients with unexplained cardiac arrest: Cardiac Arrest Survivors with Preserved Ejection Fraction Registry (CASPER). Circulation. 2009. 120:278–285.3. George CH, Higgs GV, Lai FA. Ryanodine receptor mutations associated with stress-induced ventricular tachycardia mediate increased calcium release in stimulated cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2003. 93:531–540.4. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002. 106:69–74.5. Lahat H, Eldar M, Levy-Nissenbaum E, et al. Autosomal recessive catecholamine-or exercise-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: clinical features and assignment of the disease gene to chromosome 1p13-21. Circulation. 2001. 103:2822–2827.6. Nam GB, Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Cellular mechanisms underlying the development of catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2005. 111:2727–2733.7. di Barletta MR, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Nori A, et al. Clinical phenotype and functional characterization of CASQ2 mutations associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2006. 114:1012–1019.8. Maron BJ, Chaitmann BR, Ackerman MJ, et al. Recommendations for physical activity and recreational sports participation for young patients with genetic cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2004. 109:2807–2816.9. Hayashi M, Denjoy I, Extramiana F, et al. Incidence and risk factors of arrhythmic events in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2009. 119:2426–2434.10. Postma AV, Denjoy I, Kamblock J, et al. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: RYR2 mutations, bradycardia, and follow up of the patients. J Med Genet. 2005. 42:863–870.11. Leenhardt A, Lucet V, Denjoy I, Grau F, Ngoc DD, Coumel P. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children: a 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation. 1995. 91:1512–1519.12. Watanabe H, Chopra N, Laver D, et al. Flecainide prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and humans. Nat Med. 2009. 15:380–383.13. Wilde AA, Bhuiyan ZA, Crotti L, et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2008. 358:2024–2029.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

- Thoracoscopic Left Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation for a Patient with Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia and Recurrent Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Shocks

- Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia in Children

- Ventricular Tachycardia Associated Syncope in a Patient of Variant Angina without Chest Pain

- Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia in Children: Insights and Challenges From the Current Study