J Korean Soc Transplant.

2009 Dec;23(3):237-243. 10.4285/jkstn.2009.23.3.237.

The Risk Factors of Acute Cellular Rejection in Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation:Doubting the Value of Positive Lymphocytotoxic Cross-match Results

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. jw.joh@samsung.com

- KMID: 1819846

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/jkstn.2009.23.3.237

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

The influence of lymphocytotoxic cross-match results on acute cellular rejection in adult living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) has not been well examined. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the risk factors of acute rejection, including positive lymphocytotoxic cross-match results.

METHODS

Patients inquired in this study are adults who underwent their first LDLT between June 1997 and June 2007 (n=382). We reviewed retrospectively the medical records of donors and recipients, including medical history, surgical procedures, and progress, then analyzed the risk factors of acute rejection using Cox's proportion hazard model.

RESULTS

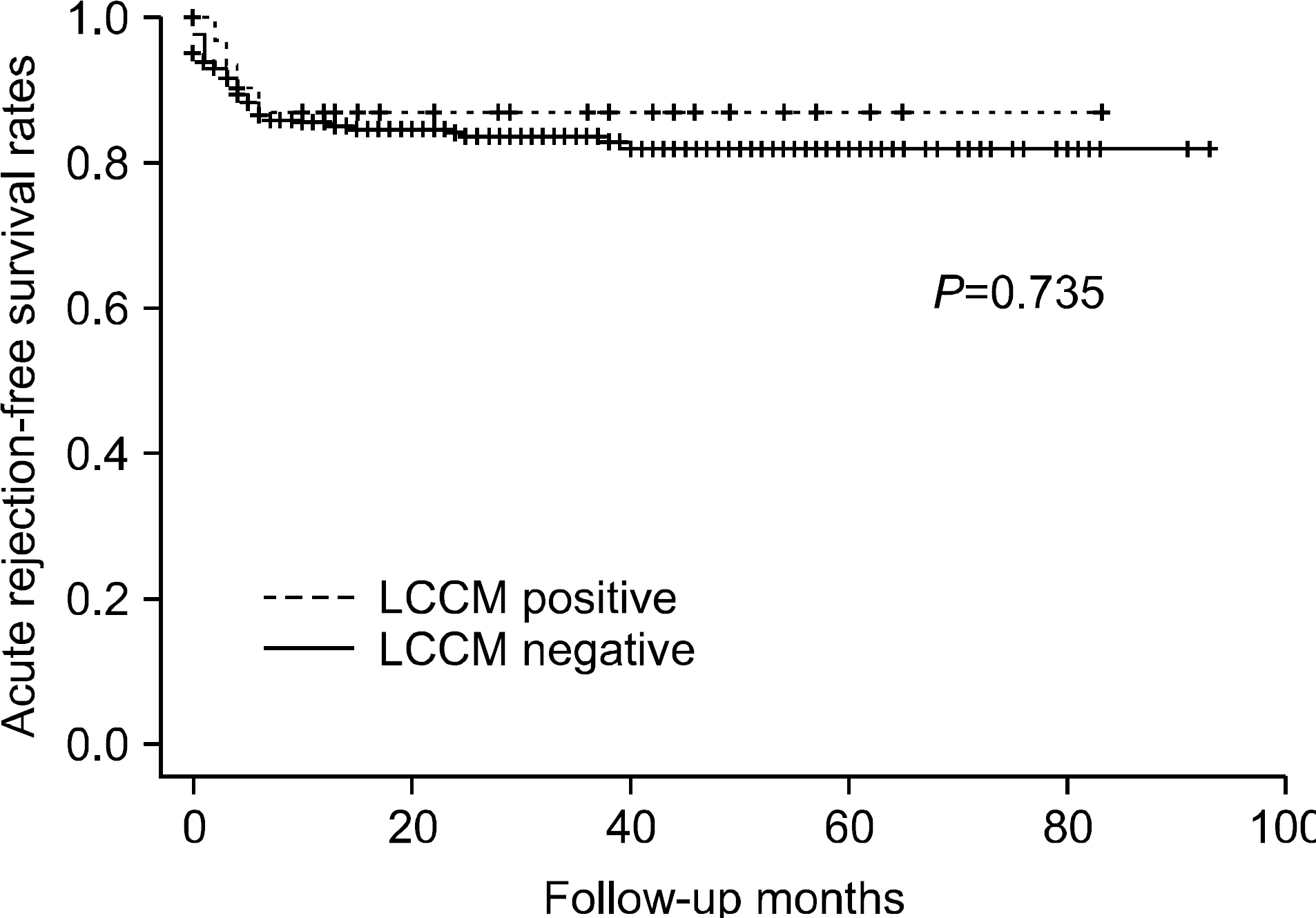

Among the total subjects of 382, 32 recipients had positive lymphocytotoxic cross-match results. Median follow-up duration was 28.0 months (range, 1~93). Fifty six recipients had suffered at least one or more acute rejection episodes. In univariate analysis, positive lymphocytotoxic cross-match results didn't turn out to be a significant risk factor of acute rejection (p=0.735), while recipient age (P=0.012), HCV-related (P=0.001), MELD score (P=0.042), gender mismatch (P=0.001) and no induction of anti-IL-2 receptor antibody (P=0.034) were revealed as risk factors for acute rejection. Recipient age (P=0.001, Hazard Ratio 0.937, 95% Confidence Interval 0.902~0.973), gender mismatch (P=0.001, Hazard Ratio 2.970, 95% Confidence Interval 1.524~5.788), HCV-related (P=0.001, Hazard Ratio 4.313, 95% Confidence Interval 1.786~10.417) were considered as significant risk factors in multivariate analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

Positive lymphocytotoxic cross-match results may not be the risk factor for acute rejection. Therefore, it should not be considered as a determinant when matching donors with recipients in adult LDLT.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1). Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M. Technical advances in living-related liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999; 6:245–53.

Article2). Takiff H, Cook DJ, Himaya NS, Mickey MR, Terasaki PI. Dominant effect of histocompatibility on ten-year kidney transplant survival. Transplantation. 1988; 45:410–5.

Article3). Zmijewski CM. Human leukocyte antigen matching in renal transplantation: review and current status. J Surg Res. 1985; 38:66–87.

Article4). Banff schema for grading liver allograft rejection: an in-ternational consensus document. Hepatology. 1997; 25:658–63.5). Gordon RD, Fung JJ, Markus B, Fox I, Iwatsuki S, Esquivel CO, et al. The antibody crossmatch in liver transplantation. Surgery. 1986; 100:705–15.6). Suh KS, Kim SB, Chang SH, Kim SH, Minn KW, Park MH, et al. Significance of positive cytotoxic crossmatch in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation using small graft volume. Liver Transpl. 2002; 8:1109–13.

Article7). Kim YD, Lee SG, Hwang S, Park KM, Kim KH, Ahn CS, et al. Analysis of relationship between positive T lymphocytotoxic and/or B lymphcytotoxic crossmatch and acute rejection in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2004; 18:183–7.8). Demetris AJ, Markus BH. Immunopathology of liver transplantation. Crit Rev Immunol. 1989; 9:67–92.9). Kerman RH. The role of crossmatching in organ transplantation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991; 115:255–9.10). Payne R, Rolfs MR. Fetomaternal leukocyte incompati-bility. J Clin Invest. 1958; 37:1756–63.

Article11). Van Rood JJ, Eernisse JG, Van Leeuwen A. Leucocyte antibodies in sera from pregnant women. Nature. 1958; 181:1735–6.

Article12). Brooks BK, Levy MF, Jennings LW, Abbasoglu O, Vodapally M, Goldstein RM, et al. Influence of donor and recipient gender on the outcome of liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996; 62:1784–7.

Article13). Charco R, Vargas V, Balsells J, Lázaro JL, Murio E, Jaurrieta E, et al. Influence of anti-HLA antibodies and positive T-lymphocytotoxic crossmatch on survival and graft rejection in human liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 1996; 24:452–9.

Article14). Wiesner RH, Demetris AJ, Belle SH, Seaberg EC, Lake JR, Zetterman RK, et al. Acute hepatic allograft rejection: incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Hepatology. 1998; 28:638–45.

Article15). Takakura K, Kiuchi T, Kasahara M, Uryuhara K, Uemoto S, Inomata Y, et al. Clinical implications of flow cytometry crossmatch with T or B cells in living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2001; 15:309–16.

Article16). Takaya S, Bronsther O, Iwaki Y, Nakamura K, Abu- Elmagd K, Yagihashi A, et al. The adverse impact on liver transplantation of using positive cytotoxic crossmatch donors. Transplantation. 1992; 53:400–6.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of Relationship between Positive T Lymphocytotoxic and/or B Lympocytotoxic Cross- Match and Acute Rejection in Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation

- The effect of a positive T-lymphocytotoxic crossmatch on clinical outcomes in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation

- HLA Cross-match Negative Conversion by Therapeutic Plasmapheresis in a Patient with Positive HLA Cross-match

- Comparison of Flow Cytometry Crossmatch with Conventional Lymphocytotoxic Crossmatch in Living Donor Renal Transplantation

- The Impact of Acute Rejection on Long-Term Graft Outcome in Renal Allograft Recipient