Korean J Urol.

2009 Aug;50(8):751-756. 10.4111/kju.2009.50.8.751.

The Preoperative Factors Predicting a Positive Frozen Section during Radical Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. cskim@amc.seoul.kr

- 2Department of Urology, Hallym Sacred Heart Hospital, University of Hallym College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1780477

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4111/kju.2009.50.8.751

Abstract

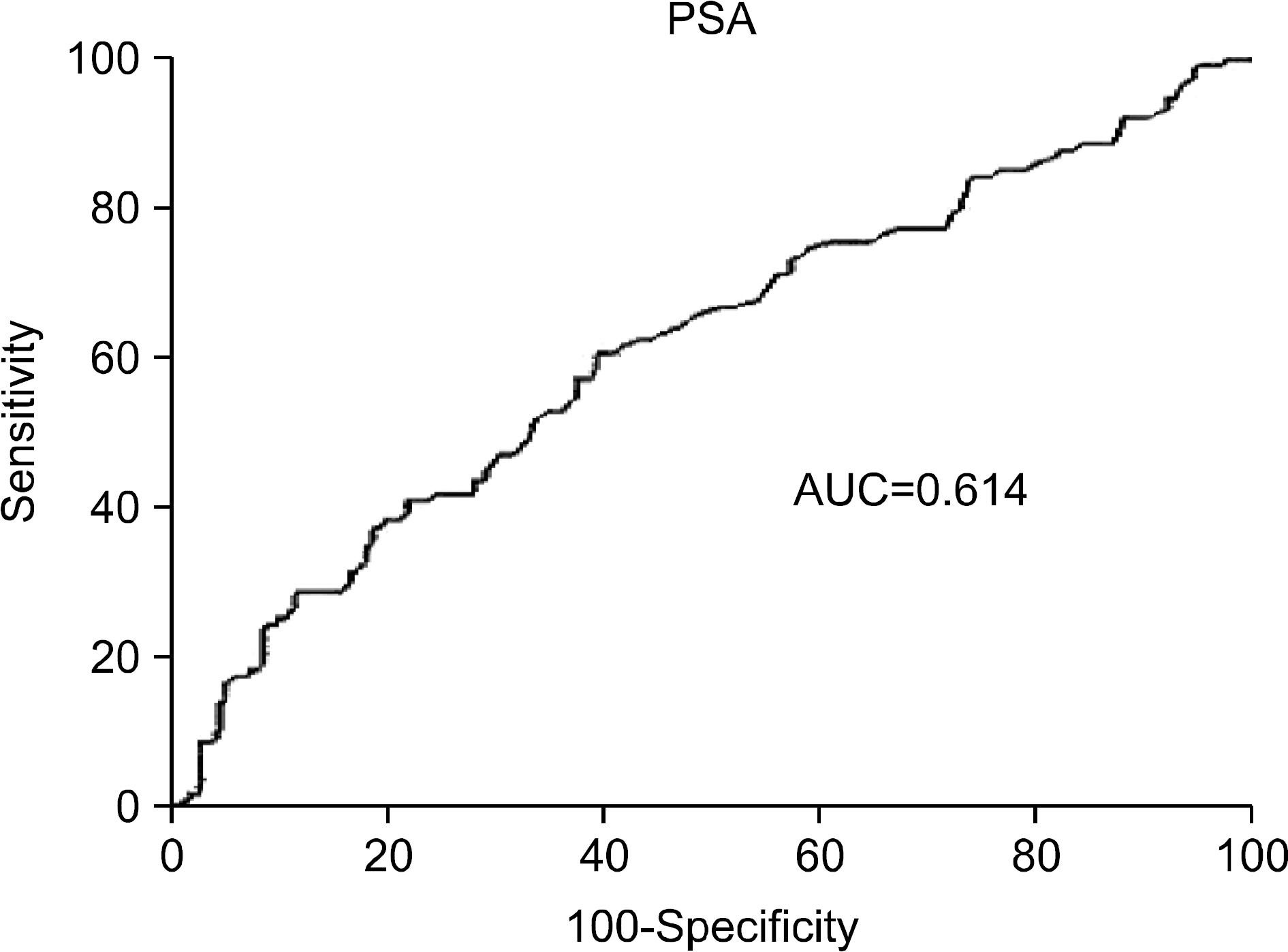

- PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to identify the preoperative factors that predict a positive frozen section during radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. MATERIALS AND METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostate volume, Gleason score, the number or percent (%) of cancer-positive cores from prostate biopsy, and the clinical stage of 364 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy between 1993 and 2007. We compared these parameters between patients who had positive frozen sections in specimens from the urethra or bladder neck with those who had negative frozen sections. RESULTS: The PSA and Gleason score were significantly higher and prostate volume was significantly smaller in patients with positive frozen sections in the urethra than in patients with negative frozen sections. The results were the same for the bladder neck. In multivariate analysis, PSA was the only independent predictor for positive frozen sections at the bladder neck, and the cutoff value was 8.71 ng/ml. CONCLUSIONS: Preoperative PSA may be a potent factor for predicting positive frozen sections during radical prostatectomy, especially in the bladder neck. Therefore, it may be beneficial to prepare frozen sections of the bladder neck during the operation to reduce the positive resection margin when PSA is higher than 8.7 ng/ml.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lepor H, Kaci L. Role of intraoperative biopsies during radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2004; 63:499–502.

Article2. Shah O, Melamed J, Lepor H. Analysis of apical soft tissue margins during radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2001; 165:1943–8.

Article3. Pfitzenmaier J, Pahernik S, Tremmel T, Haferkamp A, Buse S, Hohenfellner M. Positive surgical margins after radical prostatectomy: Do they have an impact on biochemical or clinical progression? BJU Int. 2008; 102:1413–8.

Article4. Swindle P, Eastham JA, Ohori M, Kattan MW, Wheeler T, Maru N, et al. Do margins matter? The prognostic significance of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol. 2005; 174:903–7.

Article5. Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Iocca A, Scherer B, Zincke H. Use of Gleason score, prostate specific antigen, seminal vesicle and margin status to predict biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2001; 165:119–25.

Article6. Grossfeld GD, Chang JJ, Broering JM, Miller DP, Yu J, Flanders SC, et al. Impact of positive surgical margins on prostate cancer recurrence and the use of secondary cancer treatment: data from the CaPSURE database. J Urol. 2000; 163:1171–7.

Article7. Hong JH, Lee HM, Choi HY. The predictors of biochemical recurrence and metastasis following radical perineal prostatectomy in clinically localized prostate cancer. Korean J Urol. 2005; 46:1161–7.8. Cho KS, Hong SJ, Chung BH. The impact of positive surgical margins on biochemical recurrence after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Korean J Urol. 2004; 45:416–22.9. Kim JB, Kim CS, Park JY. The impact of positive surgical margins and their preoperative predicting factors on biochemical failure after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Korean J Urol. 2003; 44:1262–8.10. Epstein JI. Pathologic assessment of the surgical specimen. Urol Clin North Am. 2001; 28:567–94.

Article11. Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Longterm biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001; 28:555–65.12. Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ornstein DK. Prostate cancer detection in men with serum PSA concentrations of 2.6 to 4.0 ng/ml and benign prostate examination. Enhancement of specificity with free PSA measurements. JAMA. 1997; 277:1452–5.

Article13. Shah O, Robbins DA, Melamed J, Lepor H. The New York University nerve sparing algorithm decreases the rate of positive surgical margins following radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003; 169:2147–52.

Article14. Lepor H, Chan S, Melamed J. The role of bladder neck biopsy in men undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy with preservation of the bladder neck. J Urol. 1998; 160:2435–9.

Article15. Cangiano TG, Litwin MS, Naitoh J, Dorey F, deKernion JB. Intraoperative frozen section monitoring of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1999; 162:655–8.16. Goharderakhshan RZ, Sudilovsky D, Carroll LA, Grossfeld GD, Marn R, Carroll PR. Utility of intraoperative frozen section analysis of surgical margins in region of neurovascular bundles at radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2002; 59:709–14.

Article17. Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al. The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99:1171–7.

Article18. Hull GW, Rabbani F, Abbas F, Wheeler TM, Kattan MW, Scardino PT. Cancer control with radical prostatectomy alone in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Urol. 2002; 167:528–34.

Article19. Kattan MW, Wheeler TM, Scardino PT. Postoperative nomogram for disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17:1499–507.

Article20. Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Riedel E, Begg CB, Wheeler TM, Gerigk C, et al. Variations among individual surgeons in the rate of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol. 2003; 170:2292–5.

Article21. Pettus JA, Weight CJ, Thompson CJ, Middleton RG, Stephenson RA. Biochemical failure in men following radical retropubic prostatectomy: impact of surgical margin status and location. J Urol. 2004; 172:129–32.

Article22. Blute ML, Bostwick DG, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Martin SK, Amling CL, et al. Anatomic site-specific positive margins in organ-confined prostate cancer and its impact on outcome after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 1997; 50:733–9.

Article23. Ohori M, Wheeler TM, Kattan MW, Goto Y, Scardino PT. Prognostic significance of positive surgical margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. J Urol. 1995; 154:1818–24.

Article24. Wieder JA, Soloway MS. Incidence, etiology, location, prevention and treatment of positive surgical margins after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998; 160:299–315.

Article25. Tsuboi T, Ohori M, Kuroiwa K, Reuter VE, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, et al. Is intraoperative frozen section analysis an efficient way to reduce positive surgical margins? Urology. 2005; 66:1287–91.

Article26. Freeland SJ, Isaacs WB, Platz EA, Terris MK, Aronson WJ, Amling CL, et al. Prostate size and risk of high-grade, advanced prostate cancer and biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy: a search database study. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:7546–54.27. Hong SK, Yu JH, Han BK, Chang IH, Jeong SJ, Byun SS, et al. Association of prostate size and tumor grade in Korean men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2007; 70:91–5.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Radical Prostatectomy

- A Case of No Residual Cancer in Radical Prostatectomy Specimens Despite Biopsy-proven Prostate Cancer

- Clinicopathological Significance of the Lymphovascular Invasion Detected in Specimens from Radical Retropubic Prostatectomies

- Predictive Factors of Gleason Score Upgrading in Localized and Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer Diagnosed by Prostate Biopsy

- Use of Serum PSA in Comparison of Biopsy Gleason Score with Radical Prostatectomy Gleason Score