J Korean Acad Nurs.

2012 Dec;42(7):1039-1049. 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.7.1039.

Individual and Environmental Factors Influencing Questionable Development among Low-income Children: Differential Impact during Infancy versus Early Childhood

- Affiliations

-

- 1College of Nursing, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, USA.

- 2Office of Research Facilitation, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, USA.

- 3College of Nursing, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea. sooy@catholic.ac.kr

- KMID: 1739542

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2012.42.7.1039

Abstract

- PURPOSE

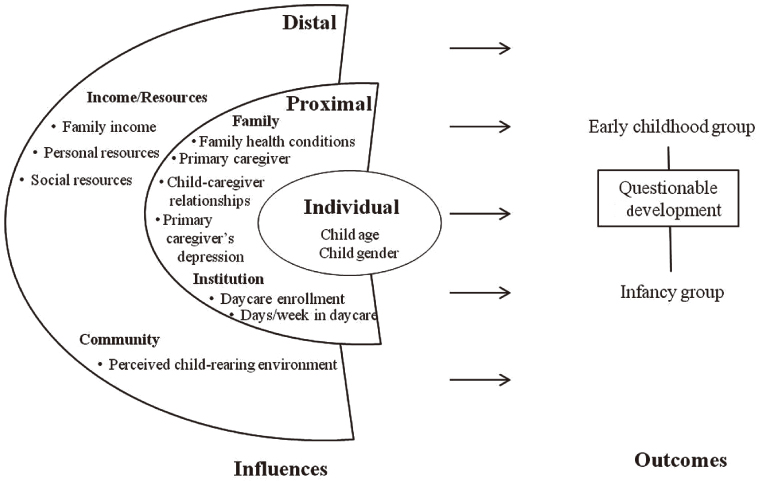

From the holistic environmental perspective, individual and environmental influences on low-income children's questionable development were identified and examined as to differences in the influences according to the child's developmental stage of infancy (age 0-35 months) or early childhood (age 36-71 months).

METHODS

This study was a cross-sectional comparative design using negative binominal regression analysis to identify predictors of questionable development separately for each developmental stage. The sample was comprised of 952 children (357 in infancy and 495 in early childhood) from low-income families in South Korea. Predictors included individual factors: child's age and gender; proximal environmental influences: family factors (family health conditions, primary caregiver, child-caregiver relationship, depression in primary caregiver) and institution factors (daycare enrollment, days per week in daycare); and distal environmental influences: income/resources factors (family income, personal resources and social resources); and community factors (perceived child-rearing environment). The outcome variable was questionable development.

RESULTS

Significant contributors to questionable development in the infancy group were age, family health conditions, and personal resources; in the early childhood group, significant contributors were gender, family health conditions, grandparent as a primary caregiver, child-caregiver relationships, daycare enrollment, and personal resources.

CONCLUSION

Factors influencing children's questionable development may vary by developmental stage. It is important to consider differences in individual and environmental influences when developing targeted interventions to ensure that children attain their optimal developmental goals at each developmental stage. Understanding this may lead nursing professionals to design more effective preventive interventions for low-income children.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Anderson LM, Shinn C, Fullilove MT, Scrimshaw SC, Fielding JE, Normand J, et al. The effectiveness of early childhood development programs. A systematic review. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Government Review]. Am J Prev Med. 2003. 24:3 Suppl. 32–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00655-4.2. Armstrong MI, Birnie-Lefcovitch S, Ungar MT. Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and childresilience: What we know. J Child Fam Stud. 2005. 14(2):269–281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10826-005-5054-4.3. Cheung YB. Zero-inflated models for regression analysis of count data: A study of growth and development. Stat Med. 2002. 21(10):1461–1469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sim.1088.4. Drachler Mde L, Marshall T, de Carvalho Leite JC. A continuous-scale measure of child development for population-based epidemiological surveys: A preliminary study using Item Response Theoryfor the Denver test. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007. 21(2):138–153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00787.x.5. Engle PL, Fernald LC, Alderman H, Behrman J, O'Gara C, Yousafzai A, et al. Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middleincome countries. [Comment]. Lancet. 2011. 378(9799):1339–1353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60889-1.6. Frankenburg WK, Dodds JB. The Denver developmental screening test. J Pediatr. 1967. 71(2):181–191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(67)80070-2.7. Fulkerson JA, Pasch KE, Perry CL, Komro K. Relationships between alcohol-related informal social control, parental monitoring and adolescent problem behaviors among racially diverse urban youth. J Community Health. 2008. 33(6):425–433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9117-5.8. Ga HY, Kwon JY. A comparison of the Korean-ages and stages questionnaires and Denver developmental delay screening test. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011. 35(3):369–374. http://dx.doi.org/10.5535/arm.2011.35.3.369.9. Gerard AB. Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI): Manual. 1994. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.10. Guedes DZ, Primi R, Kopelman BI. BINS validation-Bayley neurodevelopmental screener in Brazilian preterm children under risk conditions. Infant Behav Dev. 2011. 34(1):126–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.11.001.11. Heymann J. Forgotten families: Ending the growing crisis confronting children and working parents in the global economy. 2006. New York: Oxford University Press.12. Irwin LG, Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. Early child development: A powerful equalizer. Final report to the World Health Organization's Commission on the social determinants of health. 2007. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Early Child Development Knowledge Network.13. Jun HJ. Effect of religious activities on mental health of the elderly: Gender difference. Annual Report of Human Ecology Research Institute. 2006. 20:1–11.14. Komro KA, Flay BR, Biglan A. Creating nurturing environments: A science-based framework for promoting child health and development within high-poverty neighborhoods. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011. 14(2):111–134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0095-2.15. Lanza ST, Rhoades BL, Greenberg MT, Cox M. Modeling multiple risks during infancy to predict quality of the caregiving environment: Contributions of a person-centered approach. Infant Behav Dev. 2011. 34(3):390–406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.02.002.16. Kim SJ. Socio-demographic characteristics of a family, mother-child relationship, and children's playfulness. 2007. Seoul: Yonsei University;Unpublished master's thesis.17. Levine ME. Holistic nursing. Nurs Clin North Am. 1971. 6(2):253–264.18. Long JS, Freese J. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. 2006. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press.19. Lung FW, Chiang TL, Lin SJ, Feng JY, Chen PF, Shu BC. Gender differences of children's developmental trajectory from 6 to 60 months in the Taiwan Birth Cohort Pilot Study. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Government]. Res Dev Disabil. 2011. 32(1):100–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.09.004.20. McConnell D, Breitkreuz R, Savage A. From financial hardship to child difficulties: Main and moderating effects of perceived social support. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Government]. Child Care Health Dev. 2011. 37(5):679–691. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01185.x.21. Neuman B. The Neuman systems model. 1995. 3rd ed. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange.22. Nicholson JM, Lucas N, Berthelsen D, Wake M. Socioeconomic inequality profiles in physical and developmental health from 0-7 years: Australian national study. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Government]. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012. 66(1):81–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.103291.23. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977. 1(3):385–401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.24. Richter L. The importance of caregiver-child interactions for the survival and healthy development of young children: A review. 2004. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development, World Health Organization.25. Richter J, Janson H. A validation study of the Norwegian version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires. [Validation Studies]. Acta Paediatr. 2007. 96(5):748–752. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00246.x.26. Shin HS, Han KJ, Oh KS, Oh JJ, Ha MN. Korean Denver II test guide. 2002. Seoul: Hyunmoonsa.27. Slykerman RF, Thompson JMD, Pryor JE, Becroft DMO, Robinson E, Clark PM, et al. Maternal stress, social support and preschool children's intelligence. Early Hum Dev. 2005. 81(10):815–821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.05.005.28. Tough SC, Siever JE, Leew S, Johnston DW, Benzies K, Clark D. Maternal mental health predicts risk of developmental problems at 3 years of age: Follow up of a community based trial. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Government]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008. 8:16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-8-16.29. Votruba-Drzal E, Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Child care and low-income children's development: Direct and moderated effects. [Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Government Research Support, U.S. Government, P.H.S.]. Child Dev. 2004. 75(1):296–312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00670.x.30. Wachs TD, Black MM, Engle PL. Maternal depression: A global threat to children's health, development, and behavior and to human rights. Child Dev Perspect. 2009. 3(1):51–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00077.x.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Korean Early Childhood Education and Care Panel Study: Data Utilization Strategies for Policy and Practice

- Analysis of Risk Factors in Children with Suspected Developmental Delays on the Denver Developmental Screening Test

- Asthma in childhood: a complex, heterogeneous disease

- Factors influencing development of the infant microbiota: from prenatal period to early infancy

- Influence of infant microbiome on health and development