Lab Anim Res.

2014 Jun;30(2):79-83. 10.5625/lar.2014.30.2.79.

The potential mechanism of the detrimental effect of defibrillation prior to cardiopulmonary resuscitation in prolonged cardiac arrest model

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine and Institute of Clinical Science, Kangwon National University Hospital, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea. cjhemd@kangwon.ac.kr

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University Hospital, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 3Departmemt of Neurobiology, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- KMID: 1707447

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5625/lar.2014.30.2.79

Abstract

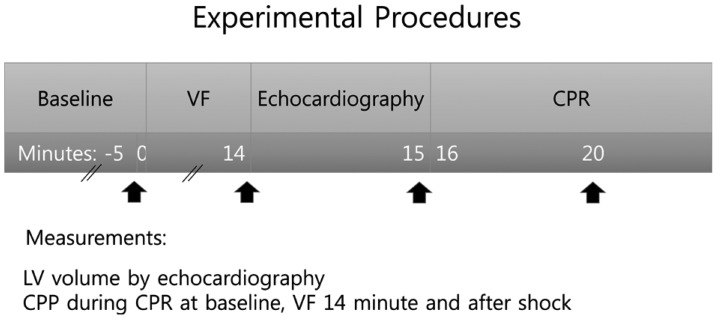

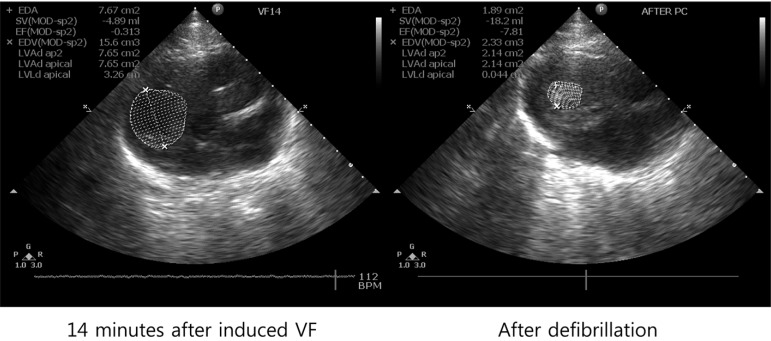

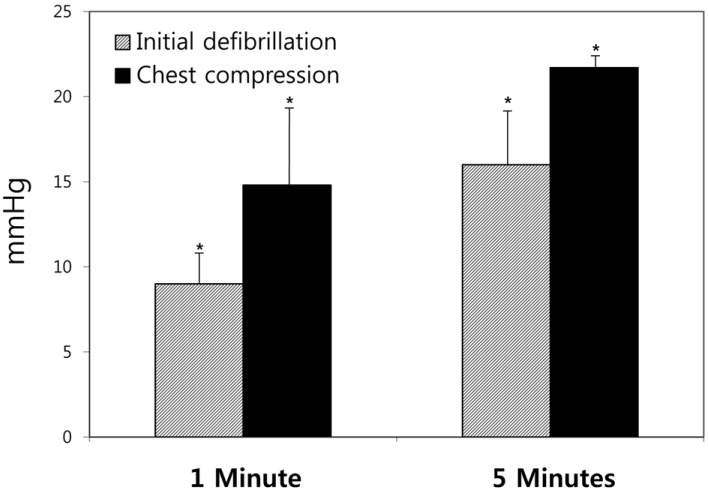

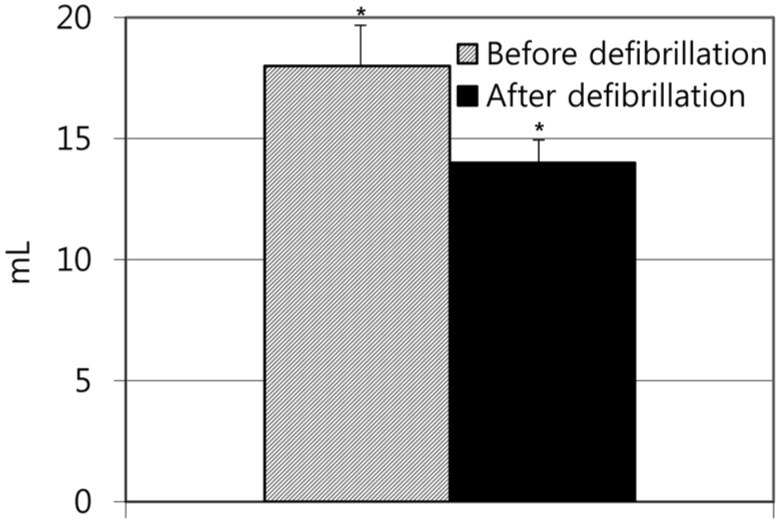

- Defibrillation is no longer universally recommended as initial intervention for the reversal of ventricular fibrillation (VF) after a prolonged and untreated cardiac arrest. We sought to examine this issue in an animal model where a prolonged untreated VF was induced. The aim of this study was to investigate the potential mechanism of the detrimental effect of defibrillation prior to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in prolonged cardiac arrest model. VF was electrically induced in 32 domestic male swine weighing 40+/-3 kg and remained untreated for 15 minutes. The animals were then randomly allocated to either the initial defibrillation group or the chest compression group. Mean aortic pressure, right atrial pressure and coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) were continuously measured during the performance. The dimensions of the left ventricle (LV) were assessed by echocardiographic methods. The CPP induced by CPR after defibrillation was significantly lower in the initial defibrillation group than in the chest compression group; 1 minute after defibrillation (9+/-3 mmHg vs. 14.8+/-7 mmHg (P<0.05)), and after 5 minutes 16+/-5 mmHg vs. 21.7+/-1 mmHg (P<0.05). The LV volumes were reduced from 18+/-2 mmHg to 14+/-1 mmHg after defibrillation (P<0.05). In brief, this study showed that the conducting defibrillation prior to chest compression may cause a contracture of the LV, resulting in lowering CPP, thus dropping the efficiency of chest compression in a prolonged cardiac arrest model.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cheung W, Flynn M, Thanakrishnan G, Milliss DM, Fugaccia E. Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Sydney, Australia. Crit Care Resusc. 2006; 8(4):321–327. PMID: 17227269.2. AHA. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care-an international consensus on science. Circulation. 2005; 112(suppl):1–4.3. Baker PW, Conway J, Cotton C, Ashby DT, Smyth J, Woodman RJ, Grantham H. Clinical Investigators. Defibrillation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation first for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrests found by paramedics to be in ventricular fibrillation? A randomised control trial. Resuscitation. 2008; 79(3):424–431. PMID: 18986748.

Article4. Hwang SO, Lim KS. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support. 3rd ed. Seoul: Koonja;2006. p. 56.5. Chandra NC. Mechanisms of blood flow during CPR. Ann Emerg Med. 1993; 22(2 Pt 2):281–288. PMID: 8434826.6. Steen S, Liao Q, Pierre L, Paskevicius A, Sjöberg T. The critical importance of minimal delay between chest compressions and subsequent defibrillation: a haemodynamic explanation. Resuscitation. 2003; 58(3):249–258. PMID: 12969599.

Article7. Rea TD, Cook AJ, Hallstrom A. CPR during ischemia and reperfusion: a model for survival benefits. Resuscitation. 2008; 77(1):6–9. PMID: 18083284.

Article8. Chamberlain D, Frenneaux M, Fletcher D. The primacy of basics in advanced life support. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009; 15(3):198–202. PMID: 19454888.

Article9. Simpson PM, Goodger MS, Bendall JC. Delayed versus immediate defibrillation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Resuscitation. 2010; 81(8):925–931. PMID: 20483525.

Article10. Berg RA, Sorrell VL, Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Altbach MI, Hayes MM, Bates KA, Ewy GA. Magnetic resonance imaging during untreated ventricular fibrillation reveals prompt right ventricular overdistention without left ventricular volume loss. Circulation. 2005; 111(9):1136–1140. PMID: 15723975.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- In-hospital Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation According to Pediatric Utstein Template

- Cardiac Arrest Due to Unrecognized Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

- Successful Resuscitation of Prolonged Cardiac Arrest Using Emergency Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenator: A case report

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: New Concept

- Thrombolytic Therapy during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in a Patient with Cardiac Arrest