J Educ Eval Health Prof.

2006;3:3.

The Future of e-Learning in Medical Education: Current Trend and Future Opportunity

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine and Department of Medical Education and Biomedical Informatics, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Box 356390 Seattle, WA 98195-7230, U.S.A. sarakim@u.washington.edu

Abstract

- A wide range of e-learning modalities are widely integrated in medical education. However, some of the key questions related to the role of e-learning remain unanswered, such as (1) what is an effective approach to integrating technology into pre-clinical vs. clinical training?; (2) what evidence exists regarding the type and format of e-learning technology suitable for medical specialties and clinical settings?; (3) which design features are known to be effective in designing on-line patient simulation cases, tutorials, or clinical exams?; and (4) what guidelines exist for determining an appropriate blend of instructional strategies, including on-line learning, face-to-face instruction, and performance-based skill practices? Based on the existing literature and a variety of e-learning examples of synchronous learning tools and simulation technology, this paper addresses the following three questions: (1) what is the current trend of e-learning in medical education?; (2) what do we know about the effective use of e-learning?; and (3) what is the role of e-learning in facilitating newly emerging competency-based training? As e-learning continues to be widely integrated in training future physicians, it is critical that our efforts in conducting evaluative studies should target specific e-learning features that can best mediate intended learning goals and objectives. Without an evolving knowledge base on how best to design e-learning applications, the gap between what we know about technology use and how we deploy e-learning in training settings will continue to widen.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. The Ad Hoc Committee of Deans. Educating doctors to provide high quality medical care: a vision for medical education in the United States [Internet]. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges;c2004. [cited 2006 Jul 20]. Available from: https://services.aamc.org/Publications/showfile.cfm?file=version27.pdf&prd_id=115&prv_id=130&pdf_id=27.2. Whitcomb ME. More on competency-based education. Acad Med. 2004; 79:493–4.

Article3. Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2006; 81:207–12.

Article4. McKimm J, Jollie C, Cantillon P. ABC of learning and teaching: Web based learning. BMJ. 2003; 326:870–3.

Article5. Smith SR. Is there a Virtual Medical School on the horizon. Med Health R I. 2003; 86:272–5.6. Walsh K. Blended learning. BMJ. 2005; 330:829.

Article7. Lau F, Bates J. A review of e-learning practices for undergraduate medical education. J Med Syst. 2004; 28:71–87.

Article8. Moberg TF, Whitcomb ME. Educational technology to facilitate medical students’ learning: background paper 2 of the medical school objectives project. Acad Med. 1999; 74:1146–50.9. Curran VR, Fleet L. A review of evaluation outcomes of web-based continuing medical education. Med Educ. 2005; Jun. 39(6):561–7.

Article10. Bell DS, Fonarow GC, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Self-study from web-based and printed guideline materials. A randomized, controlled trial among resident physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2000; 132:938–46.11. Cook DA, Dupras DM, Thompson WG, Pankratz VS. Web-based learning in residents’ continuity clinics: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med. 2005; 80:90–7.

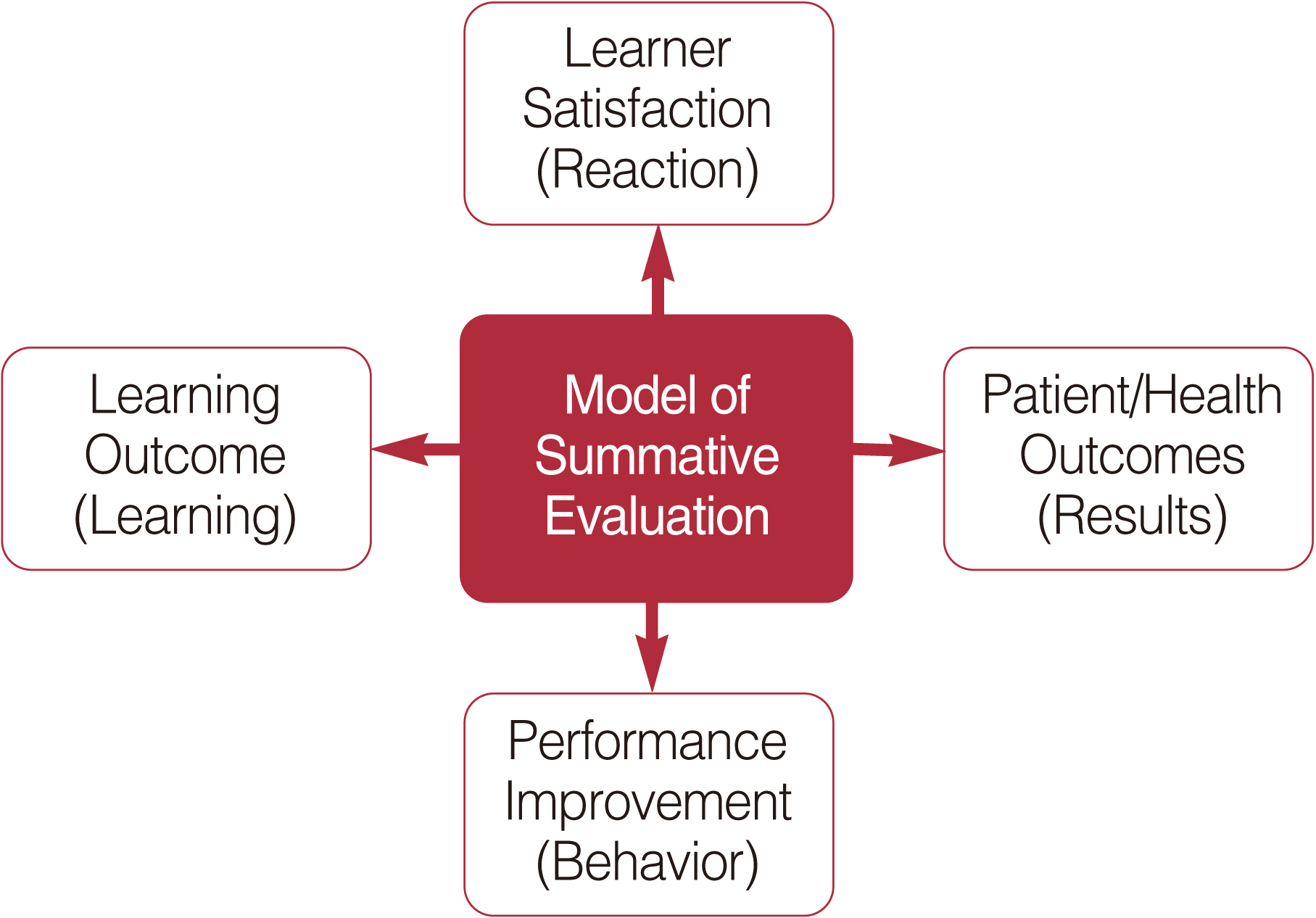

Article12. Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler;1994.13. Adler MD, Johnson KB. Quantifying the literature of computer-aided instruction in medical education. Acad Med. 2000; 75:1025–8.

Article14. Chumley-Jones HS, Dobbie A, Alford CL. Web-based learning: sound educational method or hype? A review of the evaluation literature. Acad Med. 2002; 77(10 Suppl):S86–93.15. Letterie GS. Medical education as a science: the quality of evidence for computer-assisted instruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 188:849–53.

Article16. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005; 27:10–28.17. Whitcomb ME. More on improving the education of doctors. Acad Med. 2003; 78:349–50.

Article18. Clever SL, Novack DH, Cohen DG, Levinson W. Evaluating surgeons’ informed decision making skills: pilot test using a videoconferenced standardised patient. Med Educ. 2003; 37:1094–9.

Article19. Chan DK, Gallagher TH, Reznick R, Levinson W. How surgeons disclose medical errors to patients: a study using standardized patients. Surgery. 2005; 138:851–8.

Article20. Novack DH, Cohen D, Peitzman SJ, Beadenkopf S, Gracely E, Morris J. A pilot test of WebOSCE: a system for assessing trainees’ clinical skills via teleconference. Med Teach. 2002; 24:483–7.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Future of Flexible Learning and Emerging Technology in Medical Education: Reflections from the COVID‐19 Pandemic

- Evaluation of Premedical Curriculum at Korea University

- Elective Course in Undergraduate Medical Education in Korea : Issues and Prospectives

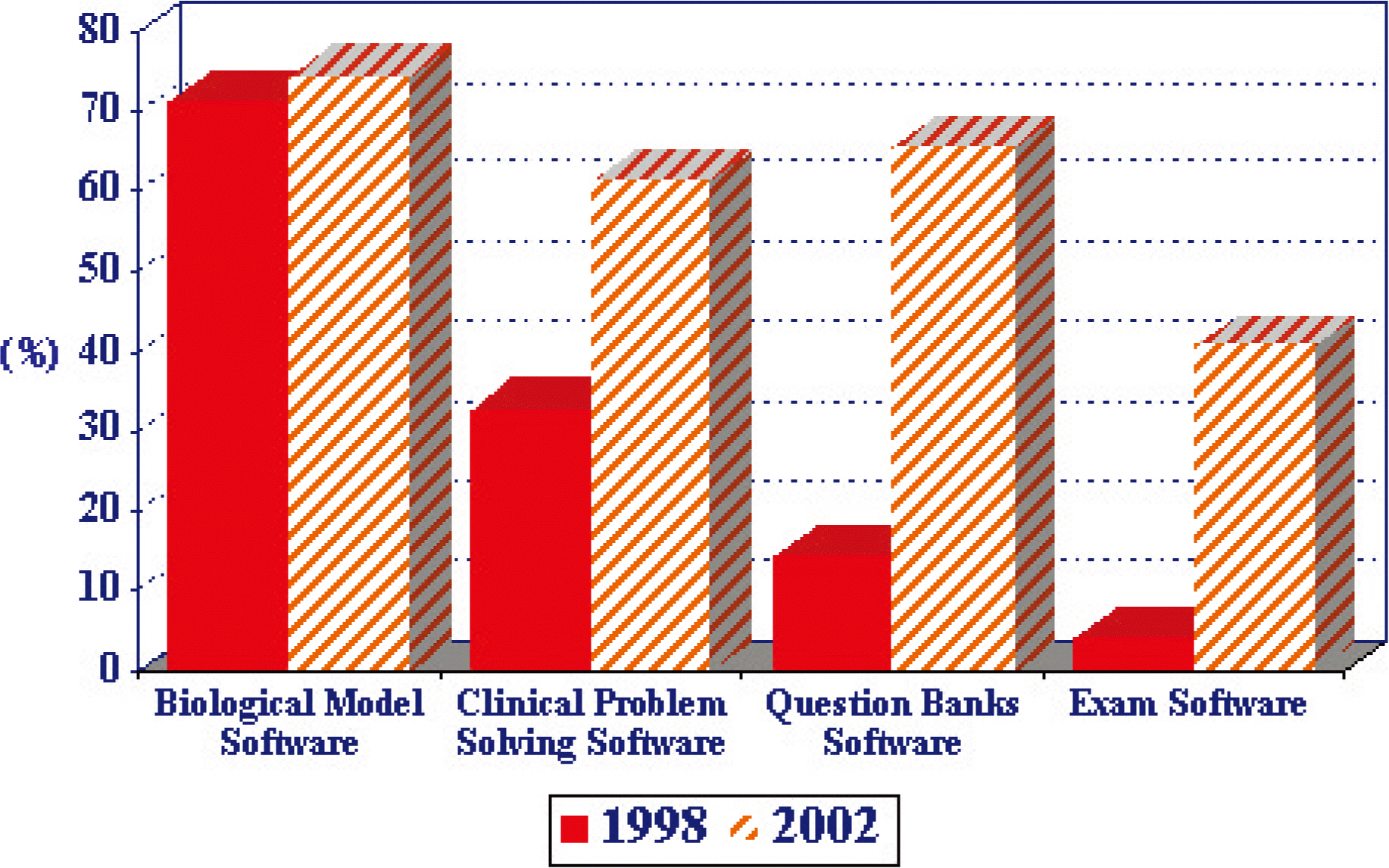

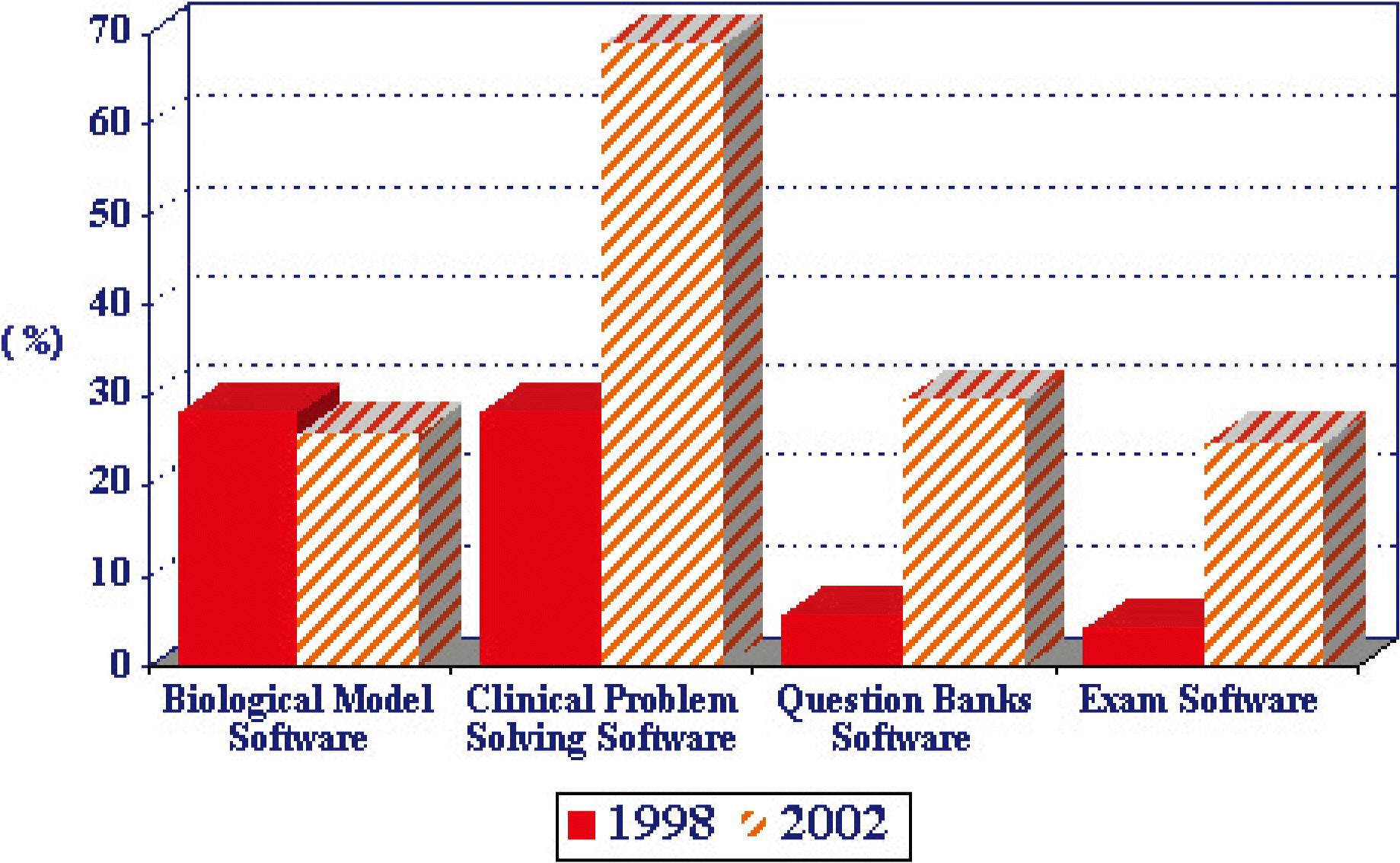

- Faculty perceptions and use of e-learning resources for medical education and future predictions

- Deep Learning in Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging: Current Perspectives and Future Directions