Lab Anim Res.

2012 Sep;28(3):209-215. 10.5625/lar.2012.28.3.209.

Evaluating the effects of pentoxifylline administration on experimental pressure sores in rats by biomechanical examinations

- Affiliations

-

- 1Cell and Molecular Biology Research Center and Anatomy Department, Medical Faculty, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. mohbayat@sbmu.ac.ir

- 2Physiotherapy Department, Medical Sciences faculty, Tarbiat Modrres University, Tehran, Iran.

- 3Sciences Faculty, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

- 4Dental Faculty, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- KMID: 1436727

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5625/lar.2012.28.3.209

Abstract

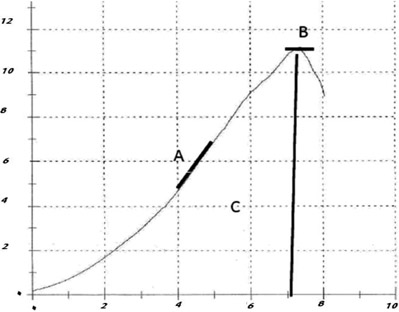

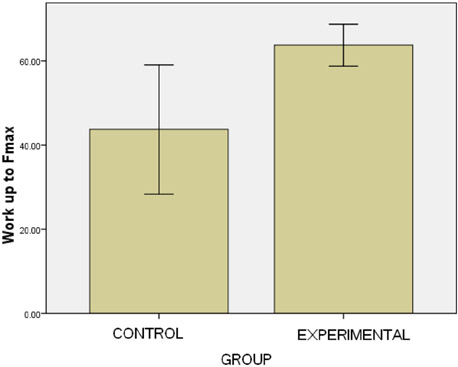

- This study used a biomechanical test to evaluate the effects of pentoxifylline administration on the wound healing process of an experimental pressure sore induced in rats. Under general anesthesia and sterile conditions, experimental pressure sores generated by no. 25 Halsted mosquito forceps were inflicted on 12 adult male rats. Pentoxifylline was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 50 mg/kg daily from the day the pressure sore was generated, for a period of 20 days. At the end of 20 days, rats were sacrificed and skin samples extracted. Samples were biomechanically examined by a material testing instrument for maximum stress (N mm2), work up to maximum force (N), and elastic stiffness (N/mm). In the experimental group, maximum stress (2.05+/-0.15) and work up to maximum force (N/mm) (63.75+/-4.97) were significantly higher than the control group (1.3+/-0.27 and 43.3+/-14.96, P=0.002 and P=0.035, respectively). Pentoxifylline administration significantly accelerated the wound healing process in experimental rats with pressure sores, compared to that of the control group.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The effects of pentoxifylline adminstration on fracture healing in a postmenopausal osteoporotic rat model

Mohammad Mahdi Vashghani Farahani, Reza Ahadi, Mohammadamin Abdollahifar, Mohammad Bayat

Lab Anim Res. 2017;33(1):15-23. doi: 10.5625/lar.2017.33.1.15.

Reference

-

1. Bass MJ, Phillips LG. Pressure sores. Curr Probl Surg. 2007. 44:101–143.2. Defloor T. The risk of pressure sores: a conceptual scheme. J Clin Nurs. 1999. 8(2):206–216.3. Meijer JH, Germs PH, Schneider H, Ribbe MW. Susceptibility to decubitus ulcer formation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994. 75(3):318–323.4. Papanikolaou P, Lyne P, Anthony D. Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcers: a methodological review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007. 44(2):285–296.5. Shahin ES, Dassen T, Halfens RJ. Pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence in intensive care patients: a literature review. Nurs Crit Care. 2008. 13(2):71–79.6. Clark M, Bours G, Delfoor T. Summery report on the prevalence of pressure ulcer. EPUAP Rev. 2002. 4:49–57.7. NPUAP. Pressure ulcer in America; prevalence, incidence and implications for the future. 2001. Reston VA: NPUAP.8. Essayan DM. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001. 108(5):671–680.9. Deree J, Martins JO, Melbostad H, Loomis WH, Coimbra R. Insights into the regulation of TNF-alpha production in human mononuclear cells: the effects of non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibition. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008. 63(3):321–328.10. Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, Guzman J, Costabel U. Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999. 159(2):508–511.11. Peters-Golden M, Canetti C, Mancuso P, Coffey MJ. Leukotrienes: underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2005. 174(2):589–594.12. Ward A, Clissold SP. Pentoxifylline. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1987. 34(1):50–97.13. Yessenow RS, Maves MD. The effects of pentoxifylline on random skin flap survival. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989. 115(2):179–181.14. Pratt MF. Edmund Prince Fowler Award Thesis. Evaluation of random skin flap survival in a porcine model. Laryngoscope. 1996. 106(6):700–712.15. Bayat M, Chelcheraghi F, Piryaei A, Rakhshan M, Mohseniefar Z, Rezaie F, Bayat M, Shemshadi H, Sadeghi Y. The effect of 30-day pretreatment with pentoxifylline on the survival of a random skin flap in the rat: an ultrastructural and biomechanical evaluation. Med Sci Monit. 2006. 12(6):BR201–BR207.16. Falanga V, Fujitani RM, Diaz C, Hunter G, Jorizzo J, Lawrence PF, Lee BY, Menzoian JO, Tretbar LL, Holloway GA, Hoballah J, Seabrook GR, McMillan DE, Wolf W. Systemic treatment of venous leg ulcers with high doses of pentoxifylline: efficacy in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 1999. 7(4):208–213.17. Dale JJ, Ruckley CV, Harper DR, Gibson B, Nelson EA, Prescott RJ. Randomised, double blind placebo controlled trial of pentoxifylline in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. BMJ. 1999. 319(7214):875–878.18. Jull A, Waters J, Arroll B. Pentoxifylline for treatment of venous leg ulcers: a systematic review. Lancet. 2002. 359(9317):1550–1554.19. De Sanctis MT, Belcaro G, Cesarone MR, Ippolito E, Nicolaides AN, Incandela L, Geroulakos G. Treatment of venous ulcers with pentoxifylline: a 12-month, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microcirculation and healing. Angiology. 2002. 53:S49–S51.20. Karasoy A, Kuran I, Turan T, Hacikerim S, Bas L, Sungan A. The effect of pentoxifylline on the healing of full-thickness skin defect on diabetic and normal rat. Eur J Plast Surg. 2002. 25:253–257.21. Peterson TC, Davey K. Effect of acute pentoxifylline treatment in an experimental model of colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997. 11(3):575–580.22. Shimizu N, Watanabe T, Arakawa T, Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Kuroki T. Pentoxifylline accelerates gastric ulcer healing in rats: roles of tumor necrosis factor alpha and neutrophils during the early phase of ulcer healing. Digestion. 2000. 61:157–164.23. Tireli GA, Salman T, Ozbey H, Abbasoglu L, Toker G, Celik A. The effect of pentoxifylline on intestinal anastomotic healing after ischemia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003. 19(1-2):88–90.24. Parra-Membrives P, Ruiz-Luque V, Escudero-Severín C, Aguilar-Luque J, Méndez-García V. Effect of pentoxifylline on the healing of ischemic colorectal anastomoses. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007. 50(3):369–375.25. Kosiak M. Etiology and pathology of ischemic ulcers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1959. 40(2):62–69.26. Werns SW, Lucchesi BR. Free radicals and ischemic tissue injury. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990. 11(4):161–166.27. Tsutakawa S, Kobayashi D, Kusama M, Moriya T, Nakahata N. Nicotine enhances skin necrosis and expression of inflammatory mediators in a rat pressure ulcer model. Br J Dermatol. 2009. 161(5):1020–1027.28. Reddy GK, Stehno-Bittel L, Enwemeka CS. Laser photostimulation accelerates wound healing in diabetic rats. Wound Repair Regen. 2001. 9(3):248–255.29. Bannister LH. Williams PH, Bannister LH, Berry MM, editors. Integumental system: Skin and Breast. Gray's Anatomy. 1995. 38th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;375–424.30. Isaac C, Mathor MB, Bariani G, Paggiaro AO, Herson MR, Goldenstein-Schainberg C, Carrasco S, Teodoro WR, Yoshinari NH, Ferreira MC. Pentoxifylline modifies three-dimensional collagen lattice model contraction and expression of collagen types I and III by human fibroblasts derived from post-burn hypertrophic scars and from normal skin. Burns. 2009. 35(5):701–706.31. Dans MJ, Isseroff R. Inhibition of collagen lattice contraction by pentoxifylline and interferon-alpha, -beta, and -gamma. J Invest Dermatol. 1994. 102(1):118–121.32. Bath PM, Bath-Hextall FJ. Pentoxifylline, propentofylline and pentifylline for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004. 3:CD000162.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The renoprotective effects of pentoxifylline: beyond its role in diabetic nephropathy

- The effects of pentoxifylline of the flap tolerance to arterial and venous ischemia in the diabetic rats

- Evaluating the Predictive Validity for the New Pressure Sores Risk Assessment Scale

- The effects of pentoxifylline adminstration on fracture healing in a postmenopausal osteoporotic rat model

- The Effect of Pentoxifylline on Rat Spinal Cord Damage to Fractionated Irradiation