Ann Lab Med.

2012 Mar;32(2):105-112. 10.3343/alm.2012.32.2.105.

Current Recommendations for Laboratory Testing and Use of Bone Turnover Markers in Management of Osteoporosis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Core Clinical Pathology and Biochemistry, PathWest-Royal Perth Hospital, WA, Australia. Samuel.Vasikaran@health.wa.gov.au

- KMID: 1245249

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2012.32.2.105

Abstract

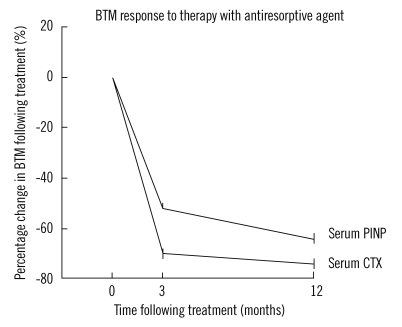

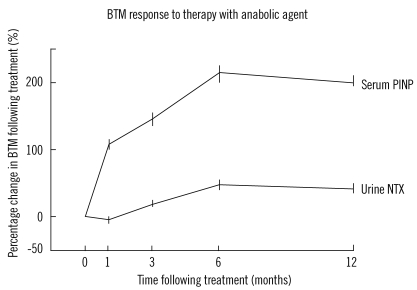

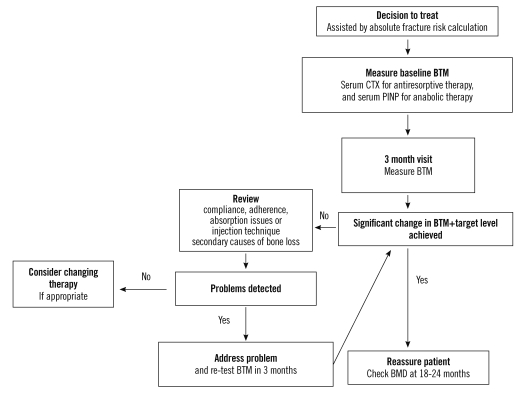

- Osteoporosis is a major health problem worldwide, and is projected to increase exponentially due to the aging of the population. The absolute fracture risk in individual subjects is calculated by the use of algorithms which include bone mineral density (BMD), age, gender, history of prior fracture and other risk factors. This review describes the laboratory investigations into osteoporosis which include serum calcium, phosphate, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase and 25-hydroxyvitamin D and, additionally in men, testosterone. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is measured in patients with abnormal serum calcium to determine its cause. Other laboratory investigations such as thyroid function testing, screening for multiple myeloma, and screening for Cushing's syndrome, are performed if indicated. Measurement of bone turnover markers (BTMs) is currently not included in algorithms for fracture risk calculations due to the lack of data. However, BTMs may be useful for monitoring osteoporosis treatment. Further studies of the reference BTMs serum carboxy terminal telopeptide of collagen type I (s-CTX) and serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) in fracture risk prediction and in monitoring various treatments for osteoporosis may help expedite their inclusion in routine clinical practice.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Development and Validation of Osteoporosis Risk-Assessment Model for Korean Men

Sun Min Oh, Bo Mi Song, Byung-Ho Nam, Yumie Rhee, Seong-Hwan Moon, Deog Young Kim, Dae Ryong Kang, Hyeon Chang Kim

Yonsei Med J. 2016;57(1):187-196. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.1.187.Measurement of Serum Levels of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D2 Using Diels-Alder Derivatization and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Hyungsuk Kim, Sun-Hee Jun, Taeksoo Kim, Sang Hoon Song, Kyoung Un Park, Junghan Song

Lab Med Online. 2012;2(4):188-196. doi: 10.3343/lmo.2012.2.4.188.

Reference

-

1. Consensus Development Conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1993; 94:646–650. PMID: 8506892.2. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ 3rd, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008; 42:467–475. PMID: 18180210.

Article3. Lim S, Koo BK, Lee EJ, Park JH, Kim MH, Shin KH, et al. Incidence of hip fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008; 26:400–405. PMID: 18600408.

Article4. Moon YW, Yoon BK, Min YK, Chang MJ, Jung SM, Lim SJ, et al. Mortality, second fracture, and functional recovery after hip fracture surgery in elderly Koreans. Korean J Bone Metab. 2008; 15:41–47.5. Lee SR, Kim SR, Chung KH, Ko DO, Cho SH, Ha YC, et al. Mortality and activity after hip fracture: a prospective study. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 2005; 40:423–427.

Article6. Kho DH, Kim KH, Shin JY, Lee JH, Kim DH. Postoperative mortality rate of hip fracture in elderly patients. J Korean Fract Soc. 2006; 19:117–121.

Article7. Statistics Korea. Updated on Dec 2011. https://www.index.go.kr/egams/stts/jsp/potal/stts/PO_STTS_IdxMain.jsp?idx_cd=1010&bbs=INDX_001.8. Cooper C, Cole ZA, Holroyd CR, Earl SC, Harvey NC, Dennison EM, et al. Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2011; 22:1277–1288. PMID: 21461721.

Article9. Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int. 1992; 2:285–289. PMID: 1421796.

Article10. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008; 19:385–397. PMID: 18292978.

Article11. Lee DY, Lim SJ, Moon YW, Min YK, Choi D, Yoon BK, Park YS. Determination of an applicable FRAX model in Korean women. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1657–1660. PMID: 21060757.

Article12. Tromp AM, Ooms ME, Popp-Snijders C, Roos JC, Lips P. Predictors of fractures in elderly women. Osteoporos Int. 2000; 11:134–140. PMID: 10793871.

Article13. Ross PD, Kress BC, Parson RE, Wasnich RD, Armour KA, Mizrahi IA. Serum bone alkaline phosphatase and calcaneus bone density predict fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int. 2000; 11:76–82. PMID: 10663362.

Article14. van Daele PL, Seibel MJ, Burger H, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, van Leeuwen JP, et al. Case-control analysis of bone resorption markers, disability, and hip fracture risk: the Rotterdam study. BMJ. 1996; 312:482–483. PMID: 8597681.

Article15. Chapurlat RD, Garnero P, Bréart G, Meunier PJ, Delmas PD. Serum type I collagen breakdown product (serum CTX) predicts hip fracture risk in elderly women: the EPIDOS study. Bone. 2000; 27:283–286. PMID: 10913923.16. Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Claustrat B, Delmas PD. Biochemical markers of bone turnover, endogenous hormones and the risk of fractures in postmenopausal women: the OFELY Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000; 15:1526–1536. PMID: 10934651.

Article17. Greenfield DM, Hannon RA, Eastell R. Eastell R, Baumann M, Hoyle N, Wieczorek L, editors. The association between bone turnover and fracture risk: The Sheffield Osteoporosis study. Bone markers - biochemical and clinical perspectives. 2001. Cachan: Lavoisier;p. 225–226.18. Garnero P, Cloos P, Sornay-Rendu E, Qvist P, Delmas PD. Type I collagen racemization and isomerization and the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women: the OFELY prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 2002; 17:826–833. PMID: 12009013.

Article19. Meier C, Nguyen TV, Center JR, Seibel MJ, Eisman JA. Bone resorption and osteoporotic fractures in elderly men: the dubbo osteoporosis epidemiology study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005; 20:579–587. PMID: 15765176.

Article20. Bauer DC, Garnero P, Harrison SL, Cauley JA, Eastell R, Ensrud KE, et al. Biochemical markers of bone turnover, hip bone loss, and fracture in older men: the MrOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009; 24:2032–2038. PMID: 19453262.

Article21. Vasikaran S, Eastell R, Bruyère O, Foldes AJ, Garnero P, Griesmacher A, et al. Markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture risk and monitoring of osteoporosis treatment: a need for international reference standards. Osteoporos Int. 2011; 22:391–420. PMID: 21184054.

Article22. Veitch SW, Findlay SC, Hamer AJ, Blumsohn A, Eastell R, Ingle BM. Changes in bone mass and bone turnover following tibial shaft fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006; 17:364–372. PMID: 16362144.

Article23. Ingle BM, Hay SM, Bottjer HM, Eastell R. Changes in bone mass and bone turnover following ankle fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1999; 10:408–415. PMID: 10591839.

Article24. Lane NE, Lukert B. The science and therapy of glucocorticoid-induced bone loss. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1998; 27:465–483. PMID: 9669150.

Article25. Deodhar AA, Woolf AD. Bone mass measurement and bone metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Br J Rheumatol. 1996; 35:309–322. PMID: 8624634.

Article26. Clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and older men (RACGP). Updated on Feb 2010. http://www.racgp.org.au/guidelines/musculoskeletaldiseases/osteoporosis.27. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011; 96:53–58. PMID: 21118827.

Article28. Glendenning P, Taranto M, Noble JM, Musk AA, Hammond C, Goldswain PR, et al. Current assays overestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and underestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 compared with HPLC: need for assay-specific decision limits and metabolite-specific assays. Ann Clin Biochem. 2006; 43:23–30. PMID: 16390606.

Article29. Glendenning P, Laffer LL, Weber HK, Musk AA, Vasikaran SD. Parathyroid hormone is more stable in EDTA plasma than in serum. Clin Chem. 2002; 48:766–767. PMID: 11978604.

Article30. Chung SH, Kim TH, Lee HH. Relationship between Vitamin D level and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women from Bucheon area. J Korean Soc Osteoporos. 2009; 7:198–202.31. Kim H, Ku SY, Kim SH, Choi YM, Moon SY, Kim JG. A study on vitamin D insufficiency in postmenopausal Korean women. J Korean Soc Osteoporos. 2003; 1:12–21.32. Park HM, Kim JG, Choi WH, Lim SK, Kim GS. The vitamin D nutritional status of postmenopausal women in Korea. Korean J Bone Metab. 2003; 10:47–55.33. So JS, Park HM. Relationship between parathyroid hormone, vitamin D and bone turnover markers in Korean postmenopausal women. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 47:153–160.34. Brown JP, Albert C, Nassar BA, Adachi JD, Cole D, Davison KS, et al. Bone turnover markers in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Biochem. 2009; 42:929–942. PMID: 19362543.

Article35. Koivula MK, Ruotsalainen V, Björkman M, Nurmenniemi S, Ikäheimo R, Savolainen K, et al. Difference between total and intact assays for N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen reflects degradation of pN-collagen rather than denaturation of intact propeptide. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010; 47:67–71. PMID: 19940208.

Article36. Marin L, Koivula MK, Jukkola-Vuorinen A, Leino A, Risteli J. Comparison of total and intact aminoterminal propeptide of type I procollagen assays in patients with breast cancer with or without bone metastases. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011; 48:447–451. PMID: 21733929.

Article37. Douglas DL, Duckworth T, Russell RG, Kanis JA, Preston CJ, Preston FE, et al. Effect of dichloromethylene diphosphonate in Paget's disease of bone and in hypercalcaemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism or malignant disease. Lancet. 1980; 1:1043–1047. PMID: 6103389.38. Fraser WD, Logue FC, Gallacher SJ, O'Reilly DS, Beastall GH, Ralston SH, et al. Direct and indirect assessment of the parathyroid hormone response to pamidronate therapy in Paget's disease of bone and hypercalcaemia of malignancy. Bone Miner. 1991; 12:113–121. PMID: 1849762.

Article39. Chesnut CH 3rd, Harris ST. Short-term effect of alendronate on bone mass and bone remodeling in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 1993; 3(Suppl 3):S17–S19. PMID: 8298198.

Article40. Maalouf NM, Heller HJ, Odvina CV, Kim PJ, Sakhaee K. Bisphosphonate-induced hypocalcemia: report of 3 cases and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2006; 12:48–53. PMID: 16524863.

Article41. McCloskey EV, Yates AJ, Gray RE, Hamdy NA, Galloway J, Kanis JA. Diphosphonates and phosphate homeostasis in man. Clin Sci (Lond). 1988; 74:607–612. PMID: 3396298.42. Vasikaran SD, O'Doherty DP, McCloskey EV, Gertz B, Kahn S, Kanis JA. The effect of alendronate on renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate. Bone Miner. 1994; 27:51–56. PMID: 7849546.

Article43. Jodrell DI, Iveson TJ, Smith IE. Symptomatic hypocalcaemia after treatment with high-dose aminohydroxypropylidene diphosphonate. Lancet. 1987; 1:622. PMID: 2881152.

Article44. Chong G, Hoang T, Davis ID. Symptomatic hypocalcaemia following intravenous pamidronate in cancer patients. Aust N Z J Med. 1999; 29:96–97. PMID: 10200826.

Article45. Garnero P, Shih WJ, Gineyts E, Karpf DB, Delmas PD. Comparison of new biochemical markers of bone turnover in late postmenopausal osteoporotic women in response to alendronate treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994; 79:1693–1700. PMID: 7989477.

Article46. Schlosser K, Scigalla P. Biochemical markers as surrogates in clinical trials in patients with metastatic bone disease and osteoporosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1997; 227:21–28. PMID: 9127465.

Article47. Braga de Castro Machado A, Hannon R, Eastell R. Monitoring alendronate therapy for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999; 14:602–608. PMID: 10234582.

Article48. Bell NH, Bilezikian JP, Bone HG 3rd, Kaur A, Maragoto A, Santora AC. Alendronate increases bone mass and reduces bone markers in postmenopausal African-American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002; 87:2792–2797. PMID: 12050252.

Article49. Greenspan SL, Parker RA, Ferguson L, Rosen HN, Maitland-Ramsey L, Karpf DB. Early changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover predict the long-term response to alendronate therapy in representative elderly women: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 1998; 13:1431–1438. PMID: 9738515.

Article50. Garnero P, Gineyts E, Arbault P, Christiansen C, Delmas PD. Different effects of bisphosphonate and estrogen therapy on free and peptidebound bone cross-links excretion. J Bone Miner Res. 1995; 10:641–649. PMID: 7610936.

Article51. Rosen HN, Dresner-Pollak R, Moses AC, Rosenblatt M, Zeind AJ, Clemens JD, et al. Specificity of urinary excretion of cross-linked N-telopeptides of type I collagen as a marker of bone turnover. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994; 54:26–29. PMID: 8118749.

Article52. Rosen HN, Moses AC, Garber J, Ross DS, Lee SL, Greenspan SL. Utility of biochemical markers of bone turnover in the follow-up of patients treated with bisphosphonates. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998; 63:363–368. PMID: 9799818.

Article53. McClung MR, Lewiecki EM, Cohen SB, Bolognese MA, Woodson GC, Moffett AH, et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:821–831. PMID: 16495394.

Article54. Rosen CJ, Hochberg MC, Bonnick SL, McClung M, Miller P, Broy S, et al. Treatment with once-weekly alendronate 70 mg compared with onceweekly risedronate 35 mg in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized double-blind study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005; 20:141–151. PMID: 15619680.

Article55. McClung MR, San Martin J, Miller PD, Civitelli R, Bandeira F, Omizo M, et al. Opposite bone remodeling effects of teriparatide and alendronate in increasing bone mass. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:1762–1768. PMID: 16087825.

Article56. Body JJ, Gaich GA, Scheele WH, Kulkarni PM, Miller PD, Peretz A, et al. A randomized double-blind trial to compare the efficacy of teriparatide [recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1-34)] with alendronate in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002; 87:4528–4535. PMID: 12364430.

Article57. Meunier PJ, Roux C, Seeman E, Ortolani S, Badurski JE, Spector TD, et al. The effects of strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:459–468. PMID: 14749454.

Article58. Bergmann P, Body JJ, Boonen S, Boutsen Y, Devogelaer JP, Goemaere S, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the use of biochemical markers of bone turnover in the selection and monitoring of bisphosphonate treatment in osteoporosis: a consensus document of the Belgian Bone Club. Int J Clin Pract. 2009; 63:19–26. PMID: 19125989.

Article59. Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd, O'Fallon WM. Drug therapy for vertebral fractures in osteoporosis: evidence that decreases in bone turnover and increases in bone mass both determine antifracture efficacy. Bone. 1996; 18(3 Suppl):197S–201S. PMID: 8777088.

Article60. Delmas PD, Seeman E. Changes in bone mineral density explain little of the reduction in vertebral or nonvertebral fracture risk with anti-resorptive therapy. Bone. 2004; 34:599–604. PMID: 15050889.

Article61. Delmas PD. Markers of bone turnover for monitoring treatment of osteoporosis with antiresorptive drugs. Osteoporos Int. 2000; 11(Suppl 6):S66–S76. PMID: 11193241.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Changes of Biochemical Markers of Bone turnover in Pre-, Peri-and Postmenopausal Women

- Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover

- Study for Usefulness of Total Alkaline Phosphatase as a Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover in Healthy Menopausal Women

- Change of Biochemical Bone Markers in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women according to their Menopausal Period

- Bone Mineral Density and Bone Turnover Markers after One-year Teriparatide Treatment in Korean Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis