Korean J Gynecol Oncol.

2008 Mar;19(1):48-56. 10.3802/kjgo.2008.19.1.48.

Induction of apoptosis by Hibiscus protocatechuic acid in human uterine leiomyoma cells

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea. chcho@kmu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea.

- KMID: 1979501

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3802/kjgo.2008.19.1.48

Abstract

-

OBJECTIVE

Hibiscus protocatechuic acid (PCA) is a food-derived polyphenol antioxidants used as a food additive and a traditional herbal medicine. In this study, PCA was to determine its effect on cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in primary cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells.

METHODS

The effect of PCA on cell proliferation and cell cycle progression was examined in the primary cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. MTT reduction assay was carried out to determine the viability of uterine leiomyoma cells. Cell cycle analysis for Hibiscus protocatechuic acid treated leiomyoma cells was done by FACS analysis. DNA fragmentation assay was performed to determine fragmentation rate by PCA in leiomyoma cells. Western blot analysis was done using anti pRB, anti-p21(cip1/waf1), anti-p53, anti-p27(kip1), anti-cyclinE, anti CDK2 antibodies to detect the presence and expression of these proteins in PCA treated myoma cells.

RESULTS

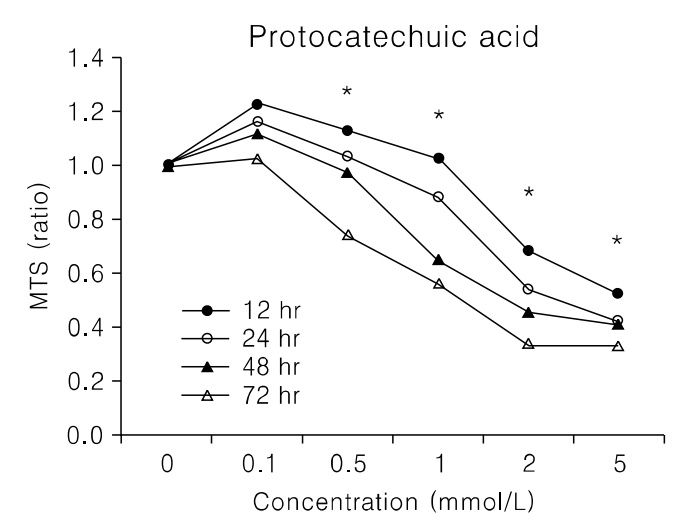

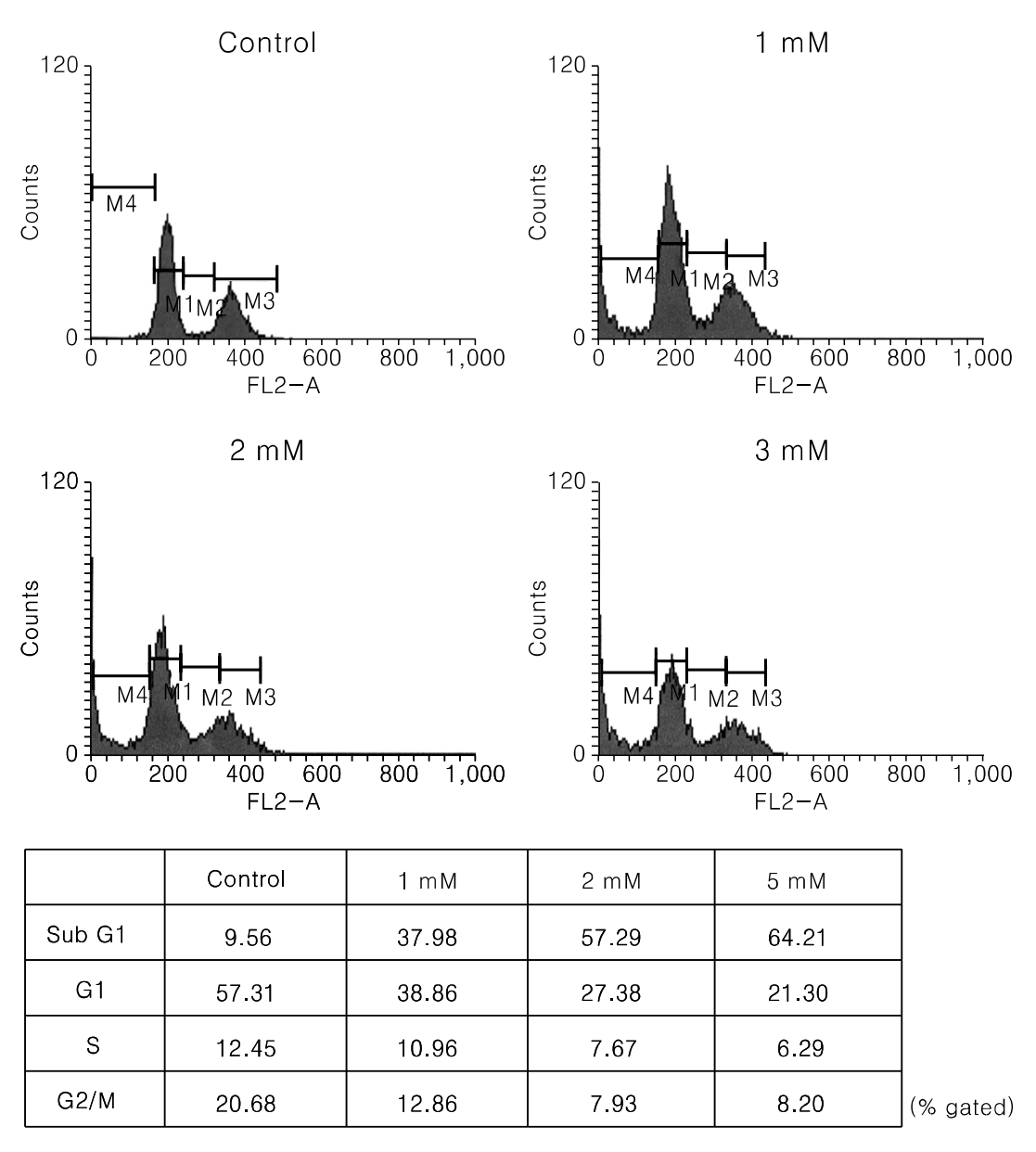

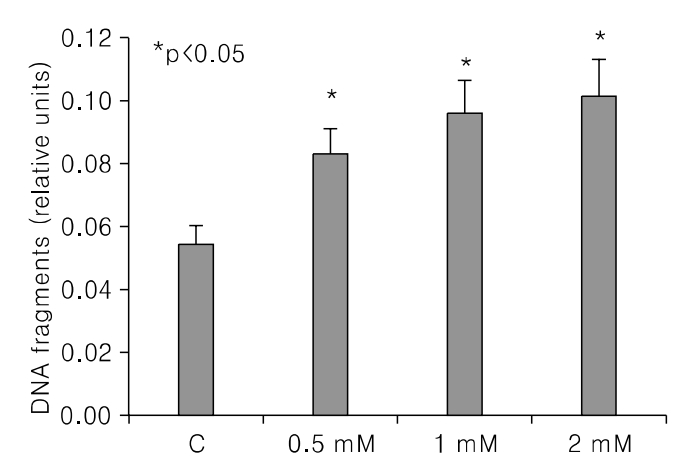

PCA induced growth inhibition in a dose dependent manner, treatment with 5 mmol/L PCA blocked 80% cell growth. FACS results showed that there was increased the percentage of cells in sub G1. DNA fragmentation assay by ELISA was done to find the rate of apoptosis. Apoptosis took place but in a dose dependent manner. From Western blot analysis it revealed PCA induced the expression of p21(cip1/waf1) and p27(kip1) increasingly and was not mediated by p53. Caspase-7 pathway was activated and dephosphorylation of pRB took place.

CONCLUSION

In Conclusions, PCA, a polyphenol antioxidant, inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell cycle arrest at sub G1 phase by enhancing the production of p21cip1/waf1 and p27kip1. These results indicate that PCA will be a promising agent for use in chemopreventive or therapeutics against human uterine leiomyoma.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Antibodies

Antioxidants

Apoptosis

Blotting, Western

Caspase 7

Cell Cycle

Cell Cycle Checkpoints

Cell Proliferation

DNA Fragmentation

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Food Additives

G1 Phase

Herbal Medicine

Hibiscus

Humans

Hydroxybenzoates

Hypogonadism

Leiomyoma

Mitochondrial Diseases

Myoma

Ophthalmoplegia

Passive Cutaneous Anaphylaxis

Proteins

Uterus

Antibodies

Antioxidants

Caspase 7

Food Additives

Hydroxybenzoates

Hypogonadism

Mitochondrial Diseases

Ophthalmoplegia

Proteins

Figure

Reference

-

1. Buttram VC Jr, Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril. 1981; 36:433–445.2. Pollow K, Sinnecker G, Boquoi E, Pollow B. In vitro conversion of estradiol-17 into estrone in normal human myometerium and leiomyoma. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1978; 16:493–502.

Article3. Clark BF. The effects of oestrogen and progesterone on uterine cell division and epithelial morphology in spayed, adrenalectomized rats. J Endocrinol. 1971; 50:527–528.

Article4. Tachi C, Tachi S, Lindner HR. Modification by progesterone of oestradiol induced cell proliferation, RNA synthesis and oestradiol distribution in the rat uterus. J Reprod Fertil. 1972; 31:59–76.5. Verkauf BS. Changing trends in treatment of leiomyomata uteri. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 5:301–310.

Article6. Corbin A, Beattie CW. Inhibition of the pre-ovulatory proestrous gonadotropin surge, ovulation and pregnancy with a peptide analogue of luteinizing hormone realizing hormone. Endocr Res Commun. 1975; 2:1–23.7. Johansen JS, Riis BJ, Hassager C, Moen M, Jacobson J, Christiansen C. The effect of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist analog (nafarelin) on bone metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988; 67:701–706.

Article8. Dawood MY, Lewis V, Ramos J. Cortical and trabecular bone mineral content in women with endometriosis: Effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and danazol. Fertil Steril. 1989; 52:21–26.9. Friedman AJ, Harrison-Atlas D, Barbieri RL, Benacerraf B, Gleason R, Schiff I. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study evaluating the efficacy of leuprolide acetate depot in the treatment of uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril. 1989; 51:251–256.10. Friedman AJ, Rein MS, Harrison-Atlas D, Garfield JM, Doubilet PM. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study evaluating leuprolide acetate depot treatment before myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 1989; 52:728–733.11. Armstrong B, Doll R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int J Cancer. 1975; 15:617–631.

Article12. Kampa M, Alexaki V, Notas G, Nifli A, Nistikaki A, Hatzoglou A, et al. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of selective phenolic acids on T47D human breast cancer cells: Potential mechanisms of action. Breast Cancer Res. 2004; 6:63–74.13. Aherne S, O\'Brien N. Dietary flavonols: Chemistry, food content and metabolism. Nutrition. 2002; 18:75–81.

Article14. Hollman P, Katan M. Dietary flavonoids: Intake, health effects and bioavailability. Food Chem Technol. 1999; 37:937–942.

Article15. Rice-Evans C, Miller N, Paganga G. Structure antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996; 20:933–956.16. Carlson KJ, Nichols DH, Schiff I. Indications for hysterectomy. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:856–860.

Article17. Benagiano G, Morini A, Primiero FM. Fibroids: Overview of current and future treatment options. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992; 99:18–22.

Article18. Wyshak G, Frisch RE, Albright NL. Lower prevalence of benign diseases of the breast and benign tumors of the reproductive system among former college athletes compared to nonathletes. Br J Cancer. 1986; 54:841–845.19. Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, Marciso S, Benzi G, Chiantera V, La Vecchia C. Diet and uterine myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 94:395–398.

Article20. DiPaola RS, Zhang H, Lambert GH, Meeker R, Licitra E, Rafi MM, et al. Clinical and biologic activity of an estrogenic herbal combination (PC-SPES) in prostate cancer. New Engl J Med. 1998; 339:785–791.

Article21. Lee H, Beak S, Cho C. Spatholobus subrectus Dunn inhibits the proliferation and induces the apoptosis in human uterine leiomyoma cells (unpulished data).22. Mori H, Matsunaga K, Tanakamaru Y, Kawabata K, Yamada Y, Sugie S, et al. Effects of protocatechuic acid, S-methylmethanethiosulfonate or 5-hydroxy-4-(2-phenyl-(E)e thenyl)-2(5H)-furanone(KYN-54)on 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced pulmonary carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Letter. 1999; 135:123–127.23. Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993; 75:805–816.

Article24. Xiong Y, Hannon GJ, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature. 1993; 366:701–704.

Article25. Kokunai T, Izawa I, Tamaki N. Overexpression of p21WAF1/CIP1 induces cell differentiation and growth inhibition in a human glioma cell line. Int J Cancer. 1998; 75:643–648.

Article26. Datto MB, Yu Y, Wang XF. Functional analysis of the transforming growth factor beta responsive elements in the WAF1/Cip1/p21 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1995; 270:28623–28628.27. Biggs JR, Kudlow JE, Kraft AS. The role of the transcription factor Sp1 in regulating the expression of the WAF1/CIP1 gene in U937 leukemic cells. J Biol Chem. 1996; 271:901–906.

Article28. Nakano K, Mizuno T, Sowa Y, Orita T, Yoshino T, Okuyama Y, et al. Butyrate activates the WAF1/Cip1 gene promoter through Sp1 sites in a p53-negative human colon cancer cell line. J Biol Chem. 1997; 272:22199–22206.

Article29. Matsuo H, Maruo T, Samoto T. Increased expression of Bcl-2 protein in human uterine leiomyoma and its up-regulation by progesterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997; 82:29–39.

Article30. Tseng TH, Kao TW, Chu CY, Chou FP, Lin WL, Wang CJ. Induction of apoptosis by Hibiscus protocatechuic acid in human leukemia cells via reduction of retinoblastoma (RB) phosphorylation and Bcl-2 expression. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2000; 60:307–315.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Growth Inhibition of Human Uterine Leiomyoma Cells by Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator

- Salinomycin inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in human uterine leiomyoma cells

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor p27(Kip1) Controls Growth and Cell Cycle Progression in Human Uterine Leiomyoma

- Growth Inhibitory Effect of Resveratrol on Uterine Leiomyoma Cells

- Uterine leiomyoma research