Korean J Radiol.

2010 Aug;11(4):425-432. 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.4.425.

Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Young Adults: Its Prevalence According to Coronary Artery Disease Risk Stratification and the CT Characteristics

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Radiology, School of Medicine, Ewha Womans University, Seoul 158-710, Korea. yookkim@ewha.ac.kr

- KMID: 984896

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2010.11.4.425

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We aimed at evaluating the prevalence and CT characteristics of occult coronary artery disease (CAD) in young Korean adults under 40 years of age by performing coronary CT angiography (CCTA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively enrolled 112 consecutive asymptomatic subjects (90 men, mean age: 35.6 +/- 3.7 years) who underwent CCTA as part of a general health evaluation. We classified the subjects into three National Cholesterol Education Program risk categories and we assessed the plaque characteristics on CCTA according to the number of involved vessels, the location and type of plaques and vascular remodeling.

RESULTS

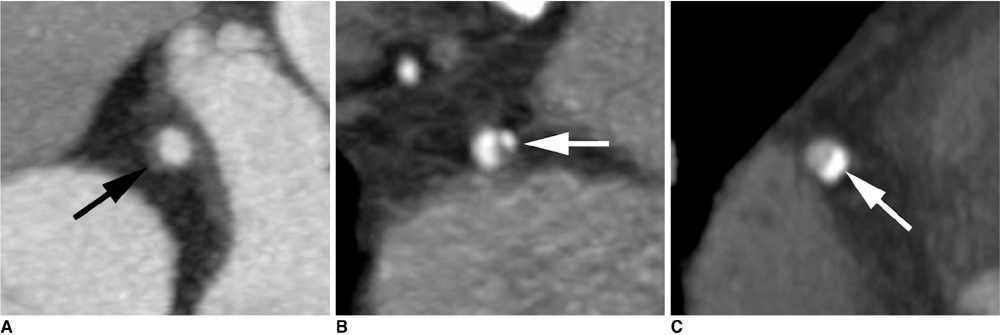

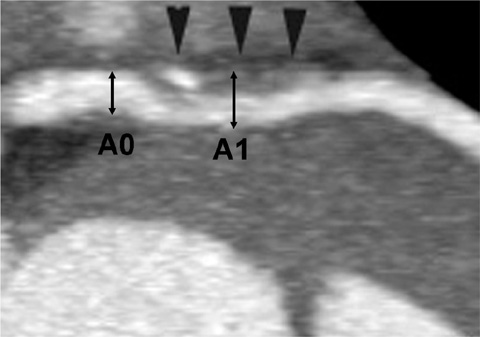

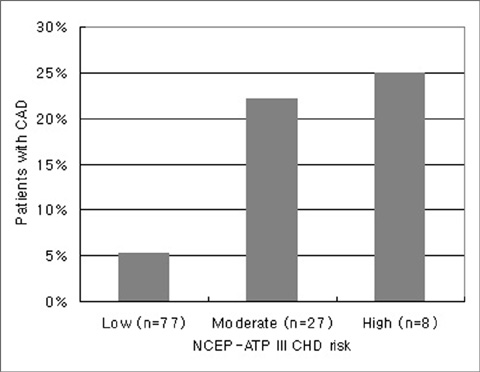

Twelve individuals had CAD (11%, 11 men). The prevalence of CAD was significantly higher in the subgroups with moderate (22%) or high (25%) risk than that in the low risk subgroup (5%) (p < 0.05). Nine patients had single-vessel disease and three patients had two-vessel disease. The most common location for plaque was the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery (60%). All the patients had non-significant stenosis and plaque, including the non-calcified (27%), mixed (47%) and calcified (27%) types. Positive vascular remodeling was identified in all the patients with non-calcified or mixed plaques.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of occult CAD was not negligible in the asymptomatic young adults with moderate to high risk, and this suggests the importance of management and risk factor modification in this population. All the patients had non-significant stenosis, and one fourth of the plaques did not show calcification.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Cooper LS, Conwill DE, Clegg L, et al. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1998. 339:861–867.2. Beaglehole R. Global cardiovascular disease prevention: time to get serious. Lancet. 2001. 358:661–663.3. Jalowiec DA, Hill JA. Myocardial infarction in the young and in women. Cardiovasc Clin. 1989. 20:197–206.4. Hoit BD, Gilpin EA, Henning H, Maisel AA, Dittrich H, Carlisle J, et al. Myocardial infarction in young patients: an analysis by age subsets. Circulation. 1986. 74:712–721.5. Cole JH, Miller JI 3rd, Sperling LS, Weintraub WS. Long-term follow-up of coronary artery disease presenting in young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. 41:521–528.6. Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975. 51:5–40.7. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002. 106:3143–3421.8. Johnson KM, Dowe DA, Brink JA. Traditional clinical risk assessment tools do not accurately predict coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden: a CT angiography study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009. 192:235–243.9. Akosah KO, Schaper A, Cogbill C, Schoenfeld P. Preventing myocardial infarction in the young adult in the first place: how do the National Cholesterol Education Panel III guidelines perform? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. 41:1475–1479.10. Choi EK, Choi SI, Rivera JJ, Nasir K, Chang SA, Chun EJ, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography as a screening tool for the detection of occult coronary artery disease in asymptomatic individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 52:357–365.11. Thaulow E, Erikssen J, Sandvik L, Erikssen G, Jorgensen L, Cohn PF. Initial clinical presentation of cardiac disease in asymptomatic men with silent myocardial ischemia and angiographically documented coronary artery disease (the Oslo Ischemia Study). Am J Cardiol. 1993. 72:629–633.12. Froelicher VF, Thompson AJ, Longo MR Jr, Triebwasser JH, Lancaster MC. Value of exercise testing for screening asymptomatic men for latent coronary artery disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1976. 18:265–276.13. Pilote L, Pashkow F, Thomas JD, Snader CE, Harvey SA, Marwick TH, et al. Clinical yield and cost of exercise treadmill testing to screen for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic adults. Am J Cardiol. 1998. 81:219–224.14. Ammann P, Marschall S, Kraus M, Schmid L, Angehrn W, Krapf R, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of myocardial infarction in patients with normal coronary arteries. Chest. 2000. 117:333–338.15. Pecora MJ, Roubin GS, Cobbs BW Jr, Ellis SG, Weintraub WS, King SB 3rd. Presentation and late outcome of myocardial infarction in the absence of angiographically significant coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1988. 62:363–367.16. Klein LW. Acute coronary syndromes in young patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 2006. 152:607–610.17. Schoenhagen P, Ziada KM, Kapadia SR, Crowe TD, Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM. Extent and direction of arterial remodeling in stable versus unstable coronary syndromes: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2000. 101:598–603.18. Tanaka M, Tomiyasu K, Fukui M, Akabame S, Kobayashi-Takenaka Y, Nakano K, et al. Evaluation of characteristics and degree of remodeling in coronary atherosclerotic lesions by 64-detector multislice computed tomography (MSCT). Atherosclerosis. 2009. 203:436–441.19. Nakamura M, Nishikawa H, Mukai S, Setsuda M, Nakajima K, Tamada H, et al. Impact of coronary artery remodeling on clinical presentation of coronary artery disease: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. 37:63–69.20. Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995. 92:657–671.21. Kullo IJ, Edwards WD, Schwartz RS. Vulnerable plaque: pathobiology and clinical implications. Ann Intern Med. 1998. 129:1050–1060.22. Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995. 92:2157–2162.23. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008. 358:1336–1345.24. Haberl R, Becker A, Leber A, Knez A, Becker C, Lang C, et al. Correlation of coronary calcification and angiographically documented stenoses in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: results of 1,764 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. 37:451–457.25. Raggi P, Callister TQ, Cooil B, He ZX, Lippolis NJ, Russo DJ, et al. Identification of patients at increased risk of first unheralded acute myocardial infarction by electron-beam computed tomography. Circulation. 2000. 101:850–855.26. Gastaldelli A, Kozakova M, Højlund K, Flyvbjerg A, Favuzzi A, Mitrakou A, et al. Fatty liver is associated with insulin resistance, risk of coronary heart disease, and early atherosclerosis in a large European population. Hepatology. 2009. 49:1537–1544.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Assessment of Prognosis and Risk Stratification in Coronary Artery Disease

- Carotid ultrasound in patients with coronary artery disease

- Three Cases of Coronary Artery Fistula from Right Coronay to Left Ventricle

- Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection and Woven Coronary Artery: Three Cases and a Review of the Literature

- Frequency of Combined Atherosclerotic Disease of the Coronary, Periphery, and Carotid Arteries Found by Angiography