J Korean Med Sci.

2025 Feb;40(7):e37. 10.3346/jkms.2025.40.e37.

Age-Stratified Risk of Severe COVID-19 for People With Disabilities in Korea: Nationwide Study Considering Disability Type

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Data Science, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA), Cheongju, Korea

- 2Department of Public Health Science, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Big Data Research and Development, National Health Insurance Service, Wonju, Korea

- KMID: 2565175

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2025.40.e37

Abstract

- Background

Understanding disparities in severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outcomes between people with disabilities (PwD) and people without disabilities (PwoD) is crucial, particularly when considering the heterogeneity within PwD and age differences. This study aimed to compare severe COVID-19 outcomes including deaths between PwD and PwoD with analyses stratified by age group and further examined by disability type.

Methods

This retrospective, population-based cohort study used linked data from national COVID-19 cases and health insurance for individuals aged ≥ 19 years with COVID-19 from January 2020 to October 2022 in the Republic of Korea. Severe outcomes included severe cases and deaths, with logistic regression analysis of the risk disparities between PwD and PwoD based on age group and disability types. The subgroup analysis considered epidemic periods, accounting for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 variant circulation.

Results

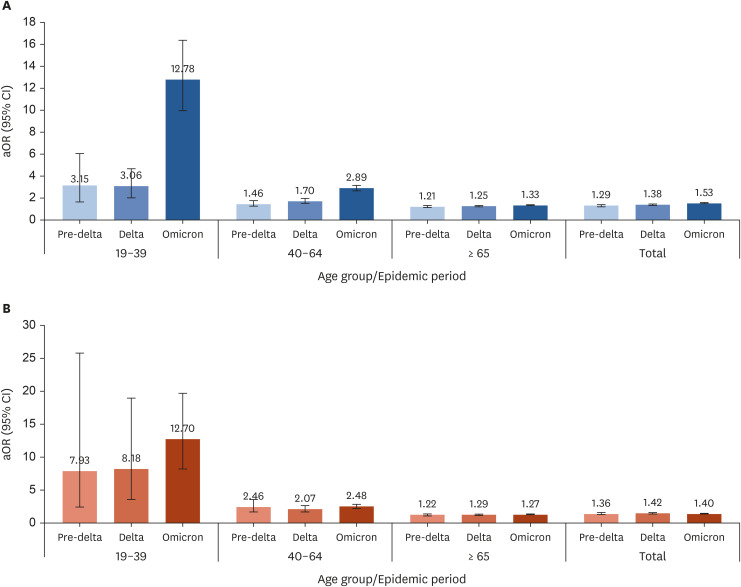

The risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes and deaths among PwD varied by age and disability type. While severe outcomes were most prevalent in the older age groups for both PwD and PwoD, younger PwD faced a markedly higher risk—up to eightfold—compared to PwoD. The risk of disability status was greater than that of comorbidities in the 19–39 age group. Among disability types, individuals with internal organs-related and intellectual disabilities showed higher risk disparities with PwoD in severe outcomes than other types of disabilities. Throughout the pandemic, the disparity in death risk remained similar, with a slight increase in disparity during the omicron period for all severe outcomes in the age groups 19–39 and 40–64 years.

Conclusion

Prioritizing younger PwD, along with older age groups and people with comorbidities, is crucial in addressing public health crises. Risk-based prioritization is important to reduce overall risk. This includes prioritizing people with nternal organs-related and intellectural disabilities, who face higher health risks among PwD during a pandemic when resources are limited and time is of the essence.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities p.312. Updated 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/global-report-on-health-equity-for-persons-with-disabilities. .2. Bosworth ML, Ayoubkhani D, Nafilyan V, Foubert J, Glickman M, Davey C, et al. Deaths involving COVID-19 by self-reported disability status during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in England: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2021; 6(11):e817–e825. PMID: 34626547.3. Choi JW, Han E, Lee SG, Shin J, Kim TH. Risk of COVID-19 and major adverse clinical outcomes among people with disabilities in South Korea. Disabil Health J. 2021; 14(4):101127. PMID: 34134944.4. Yuan Y, Thierry JM, Bull-Otterson L, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Clark KE, Rice C, et al. COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries with and without disabilities – United States, January 1, 2020-November 20, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71(24):791–796. PMID: 35709015.5. Landes SD, Turk MA, Wong AW. COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability in California: the importance of type of residence and skilled nursing care needs. Disabil Health J. 2021; 14(2):101051. PMID: 33309535.6. Turk MA, Landes SD, Formica MK, Goss KD. Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. Disabil Health J. 2020; 13(3):100942. PMID: 32473875.7. Koks-Leensen MC, Schalk BW, Bakker-van Gijssel EJ, Timen A, Nägele ME, van den Bemd M, et al. Risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes among persons with intellectual disabilities, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023; 29(1):118–126. PMID: 36573557.8. Bahk J, Kang HY, Khang YH. Disability type-specific mortality patterns and life expectancy among disabled people in South Korea using 10-year combined data between 2008 and 2017. Prev Med Rep. 2022; 29:101958. PMID: 36161125.9. Clarke KE, Hong K, Schoonveld M, Greenspan AI, Montgomery M, Thierry JM. Severity of coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalization outcomes and patient disposition differ by disability status and disability type. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 76(5):871–880. PMID: 36259559.10. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin-Blake S. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018; 67(32):882–887. PMID: 30114005.11. Kirk-Wade E, Stiebahl S, Wong H. UK Disability Statistics: Prevalence and Life Experiences. London, UK: House of Commons Library;2024.12. Molani S, Hernandez PV, Roper RT, Duvvuri VR, Baumgartner AM, Goldman JD, et al. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 differ by age for hospitalized adults. Sci Rep. 2022; 12(1):6568. PMID: 35484176.13. Brown HK, Saha S, Chan TC, Cheung AM, Fralick M, Ghassemi M, et al. Outcomes in patients with and without disability admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2022; 194(4):E112–E121. PMID: 35101870.14. Henderson A, Fleming M, Cooper SA, Pell JP, Melville C, Mackay DF, et al. COVID-19 infection and outcomes in a population-based cohort of 17 203 adults with intellectual disabilities compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022; 76(6):550–555. PMID: 35232778.15. World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. Updated 2021. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/. .16. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act. Cheongju, Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2022.17. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, Park JH, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. Data resource profile: the national health information database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(3):799–800. PMID: 27794523.18. World Health Organization. WHO R&D blueprint novel coronavirus COVID-19 therapeutic trial synopsis. Updated 2020. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/blue-print/covid-19-therapeutic-trial-synopsis.pdf. .19. Ryu B, Shin E, Kim NY, Kim DH, Lee HJ, Kim A, et al. Severity of COVID-19 associated with SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating in the Republic of Korea. Public Health Weekly Report. 2022; 15(47):2873–2895.20. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). Act on the Welfare of Persons with Disabilities. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2021.21. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020; 584(7821):430–436. PMID: 32640463.22. Das-Munshi J, Chang CK, Bakolis I, Broadbent M, Dregan A, Hotopf M, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in people with mental disorders and intellectual disabilities, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021; 11:100228. PMID: 34877563.23. Bigdelou B, Sepand MR, Najafikhoshnoo S, Negrete JA, Sharaf M, Ho JQ, et al. COVID-19 and preexisting comorbidities: risks, synergies, and clinical outcomes. Front Immunol. 2022; 13:890517. PMID: 35711466.24. World Health Organization. Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Updated 2020. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Disability-2020-1 .25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19: information for healthcare professionals. Updated 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html. .26. Sohn M, Koo H, Choi H, Cho H, Han E. Collateral impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of healthcare resources among people with disabilities. Front Public Health. 2022; 10:922043. PMID: 35991017.27. McBride-Henry K, Nazari Orakani S, Good G, Roguski M, Officer TN. Disabled people’s experiences accessing healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023; 23(1):346. PMID: 37024832.28. Kamalakannan S, Bhattacharjya S, Bogdanova Y, Papadimitriou C, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Bentley J, et al. Health risks and consequences of a COVID-19 infection for people with disabilities: scoping review and descriptive thematic analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4348. PMID: 33923986.29. Deal JA, Jiang K, Betz JF, Clemens GD, Zhu J, Reed NS, et al. COVID-19 clinical outcomes by patient disability status: a retrospective cohort study. Disabil Health J. 2023; 16(2):101441. PMID: 36764842.30. Cuypers M, Koks-Leensen MC, Schalk BW, Bakker-van Gijssel EJ, Leusink GL, Naaldenberg J. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among people with and without intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2023; 8(5):e356–e363. PMID: 37075779.31. World Health Organization, World Bank. World report on disability 2011. Updated 2011. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability. .32. Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, Scott AM, Clark J, To EJ, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(3):e045343.33. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disability and ageing Australian population patterns and implications. Updated 2000. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/disability-and-ageing-australian-population/summary .34. Landes SD, Stevens JD, Turk MA. Heterogeneity in age at death for adults with developmental disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019; 63(12):1482–1487. PMID: 31313415.35. National Rehabilitation Center Research Institute. 2020 Healthcare Statistics of Persons with Disabilities. Seoul, Korea: National Rehabilitation Center Research Institute;2022.36. Brandenburg JE, Fogarty MJ, Sieck GC. Why individuals with cerebral palsy are at higher risk for respiratory complications from COVID-19. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020; 13(3):317–327. PMID: 33136080.37. Kim Y, Eun SJ, Kim WH, Lee BS, Leigh JH, Kim JE, et al. A new disability-related health care needs assessment tool for persons with brain disorders. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013; 46(5):282–290. PMID: 24137530.38. Akobirshoev I, Vetter M, Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Mitra M. Delayed medical care and unmet care needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic among adults with disabilities in the US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022; 41(10):1505–1512. PMID: 36190876.39. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. The National survey on persons with disabilities. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2017.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Why Fast COVID-19 Vaccination Needed for People with Disabilities and Autistics in Korea?

- COVID-19 infection among people with disabilities in 2021 prior to the Omicron-dominant period in the Republic of Korea: a cross-sectional study

- Differences in Obesity Rates Between People With and Without Disabilities and the Association of Disability and Obesity: A Nationwide Population Study in South Korea

- Nationwide trends in the incidence of tuberculosis among people with disabilities in Korea: a nationwide serial cross-sectional study

- Current Status and Associated Factors of Emotional Distress Due to COVID-19 Among People with Physical Disabilities Living in the Community: Secondary Data Analysis using the 2020 National Survey of Disabled Persons