J Pathol Transl Med.

2024 Nov;58(6):283-290. 10.4132/jptm.2024.10.17.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cytology in pregnancy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pathology, CHA University School of Medicine, CHA Gangnam Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2560669

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2024.10.17

Abstract

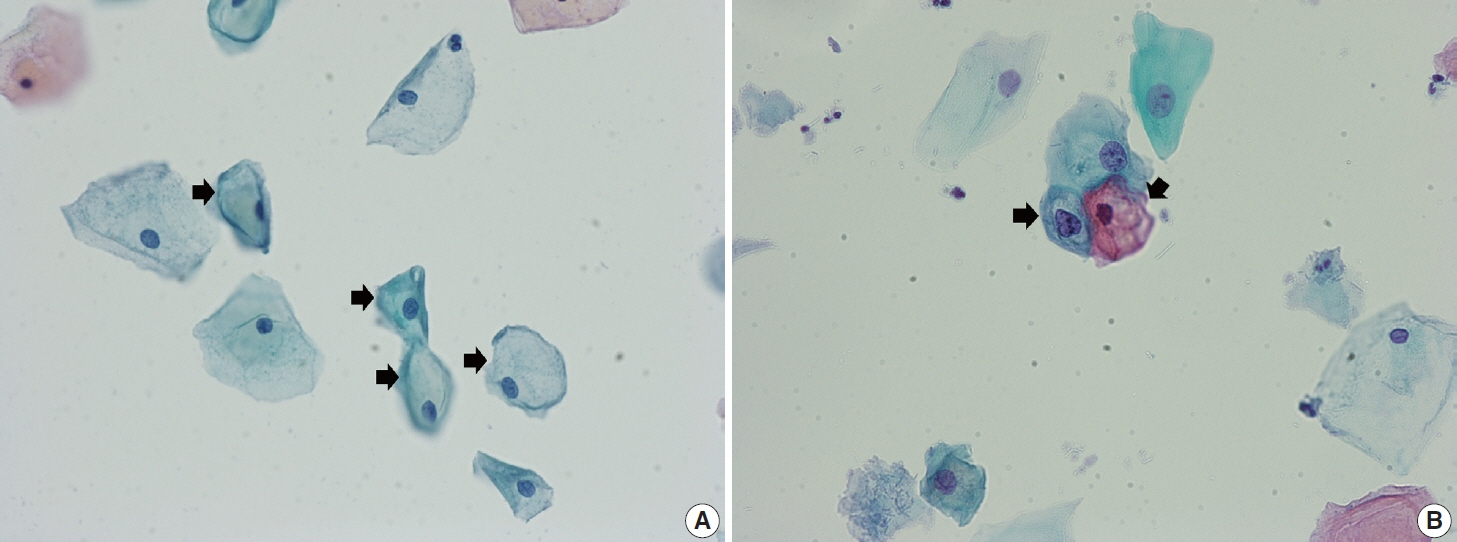

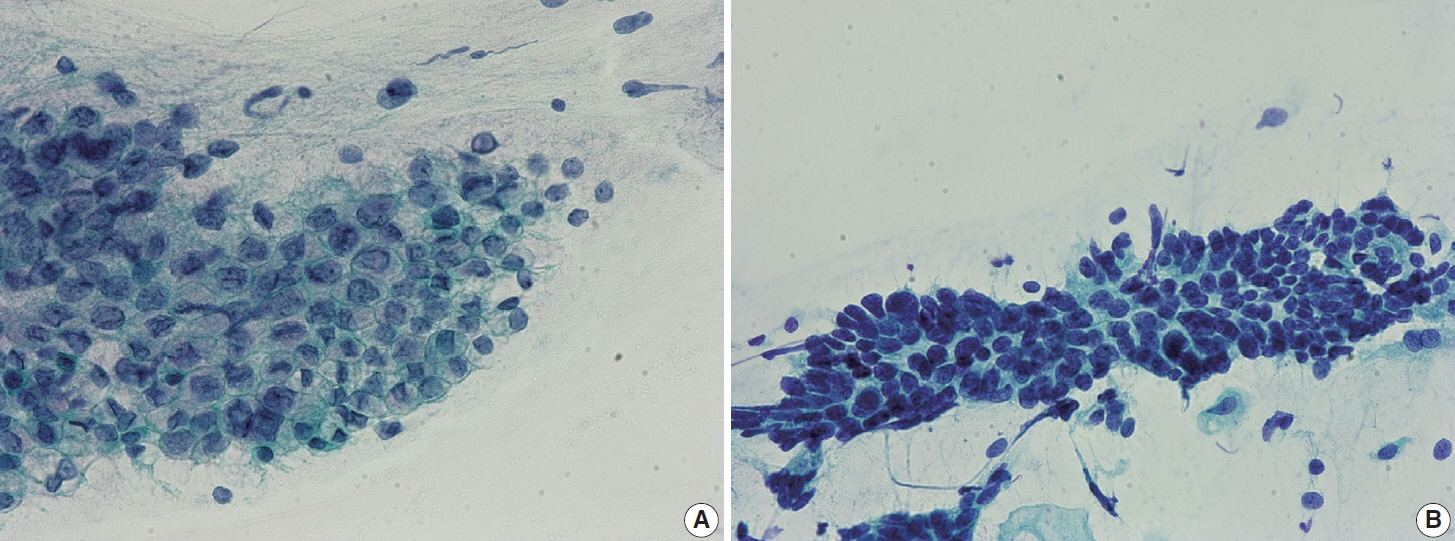

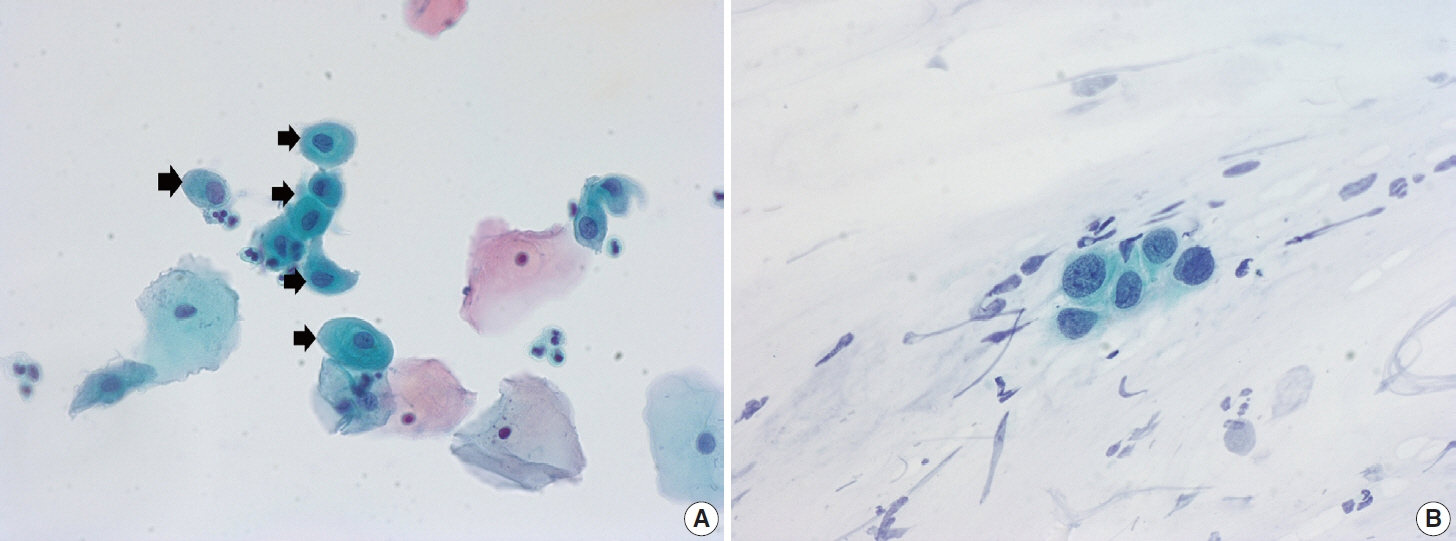

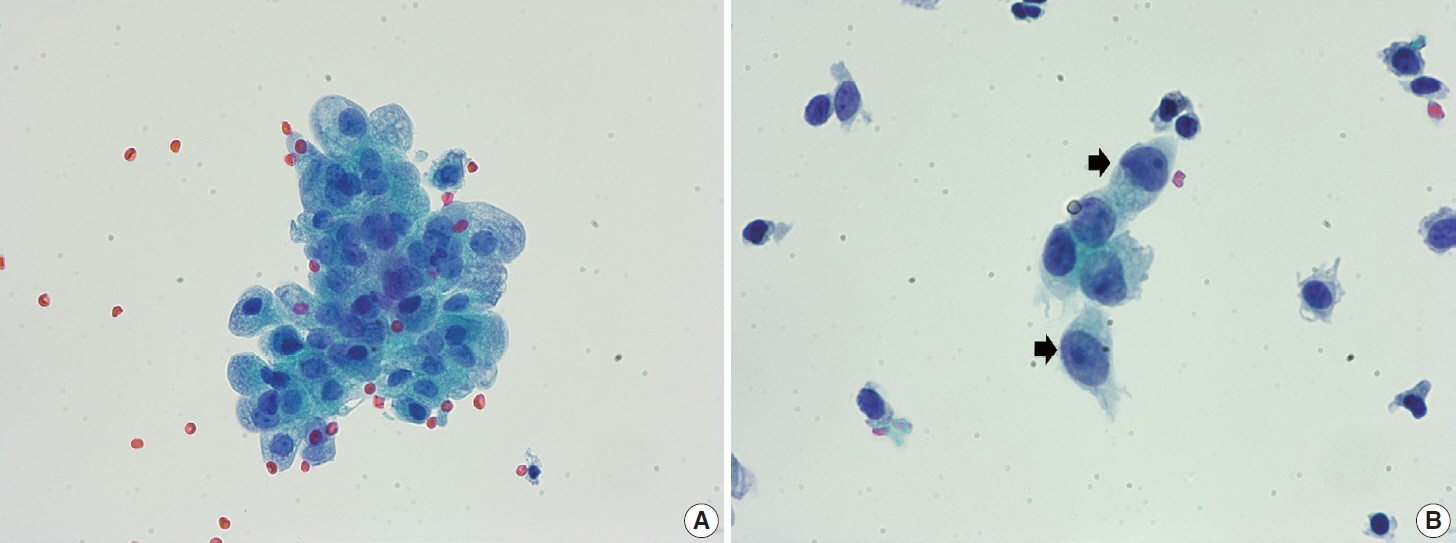

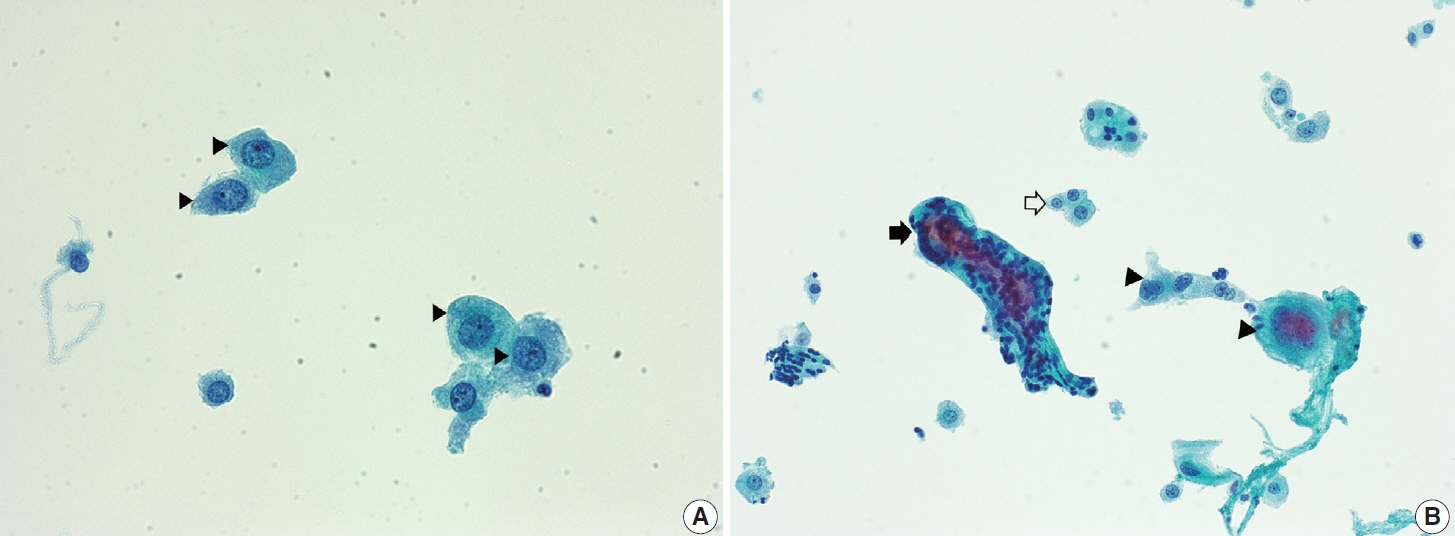

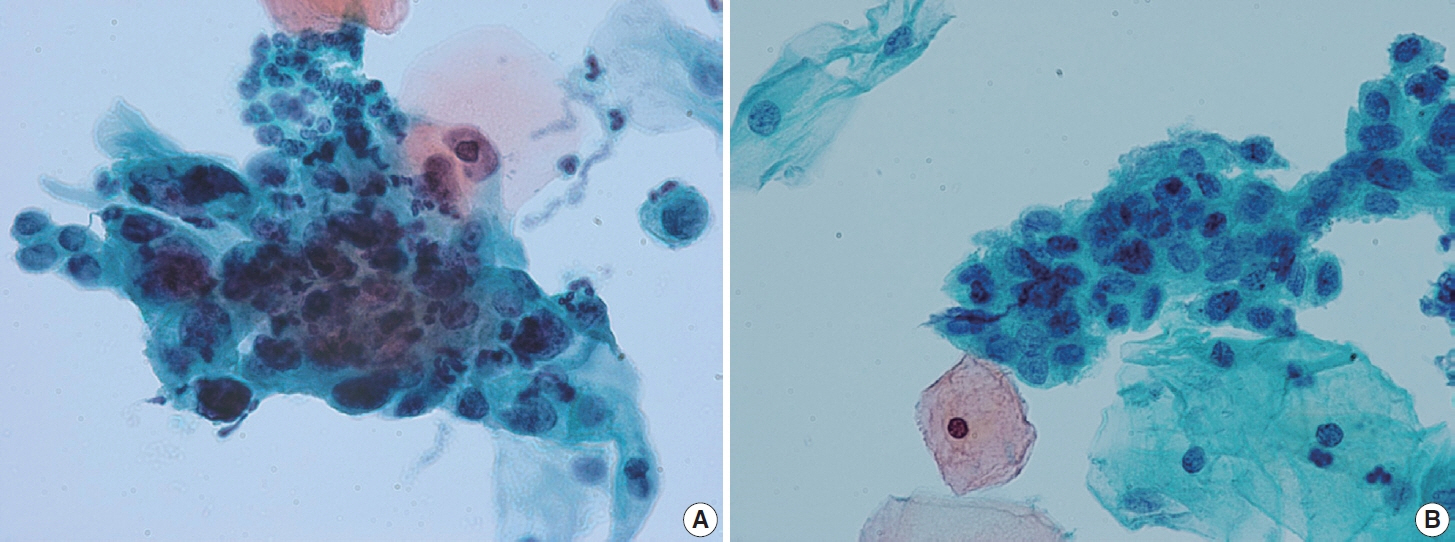

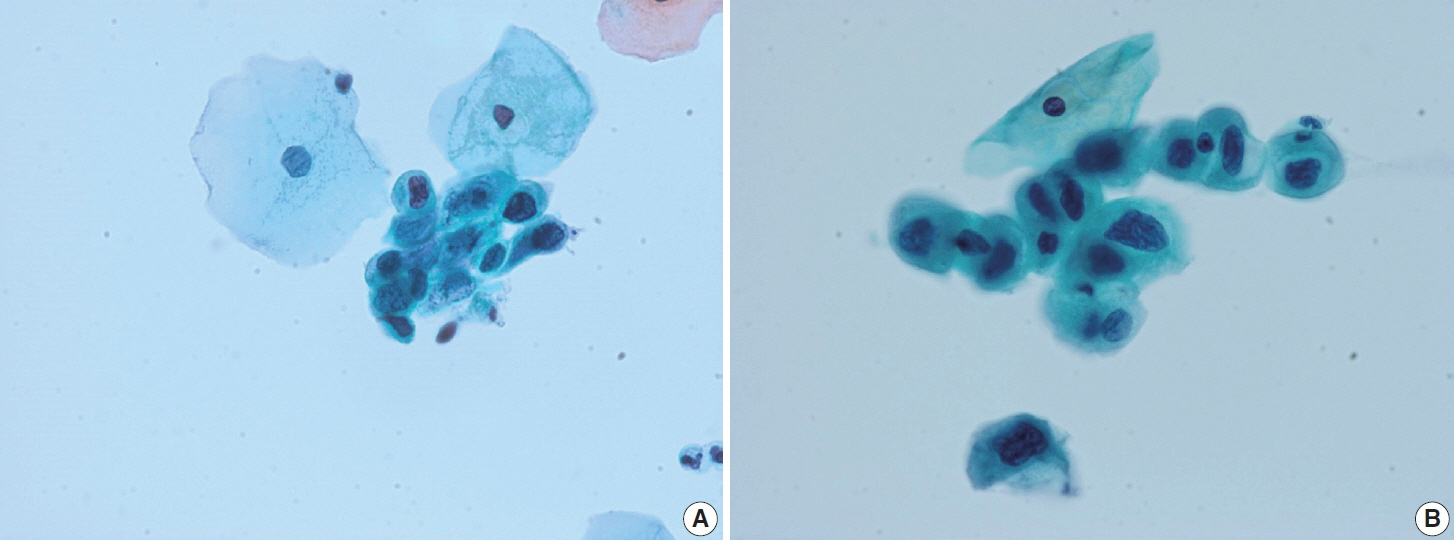

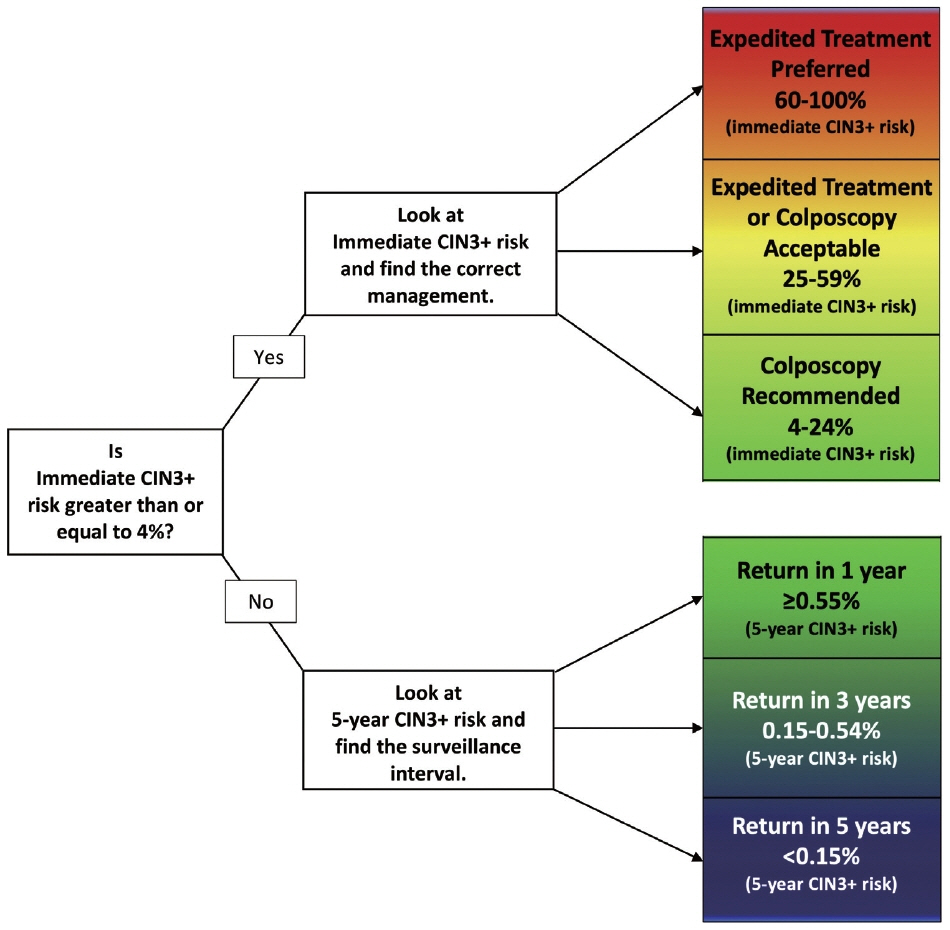

- Cervical cancer screening during pregnancy presents unique challenges for cytologic interpretation. This review focuses on pregnancy-associated cytomorphological changes and their impact on diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer. Pregnancy-induced alterations include navicular cells, hyperplastic endocervical cells, immature metaplastic cells, and occasional decidual cells or trophoblasts. These changes can mimic abnormalities such as koilocytosis, adenocarcinoma in situ, and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, potentially leading to misdiagnosis. Careful attention to nuclear features and awareness of pregnancy-related changes are crucial for correct interpretation. The natural history of CIN during pregnancy shows higher regression rates, particularly for CIN 2, with minimal risk of progression. Management of abnormal cytology follows modified risk-based guidelines to avoid invasive procedures, with treatment typically deferred until postpartum. The findings reported in this review emphasize the importance of considering pregnancy status in cytological interpretation, highlight potential problems, and provide guidance on differentiating benign pregnancy-related changes from true abnormalities. Understanding these nuances is essential for accurate diagnosis and proper management of cervical abnormalities in pregnant women.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Nguyen C, Montz FJ, Bristow RE. Management of stage I cervical cancer in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000; 55:633–43.

Article2. Norstrom A, Jansson I, Andersson H. Carcinoma of the uterine cervix in pregnancy: a study of the incidence and treatment in the western region of Sweden 1973 to 1992. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997; 76:583–9.

Article3. Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Cancer and pregnancy: poena magna, not anymore. Eur J Cancer. 2006; 42:126–40.

Article4. Al-Halal H, Kezouh A, Abenhaim HA. Incidence and obstetrical outcomes of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer in pregnancy: a population-based study on 8.8 million births. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013; 287:245–50.

Article5. Kumari S. Screening for cervical cancer in pregnancy. Oncol Rev. 2023; 17:11429.

Article6. Eibye S, Kjaer SK, Mellemkjaer L. Incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer in Denmark, 1977-2006. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122:608–17.

Article7. Eibye S, Kruger Kjaer S, Nielsen TS, Mellemkjaer L. Mortality among women with cervical cancer during or shortly after a pregnancy in Denmark 1968 to 2006. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016; 26:951–8.

Article8. Yang KY. Abnormal pap smear and cervical cancer in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 55:838–48.

Article9. Suzuki S, Hayata E, Hoshi SI, et al. Current status of cervical cytology during pregnancy in Japan. PLoS One. 2021; 16:e0245282.

Article10. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 125:330–7.11. Watson M, Benard V, King J, Crawford A, Saraiya M. National assessment of HPV and Pap tests: changes in cervical cancer screening, National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med. 2017; 100:243–7.

Article12. Xhaja A, Ahr A, Zeiser I, Ikenberg H. Two years of cytology and HPV co-testing in Germany: initial experience. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2022; 82:1378–86.

Article13. Gu L, Hu Y, Wei Y, et al. Optimising cervical cancer screening during pregnancy: a study of liquid-based cytology and HPV DNA cotest. Epidemiol Infect. 2024; 152:e25.

Article14. Zagorianakou N, Mitrogiannis I, Konis K, Makrydimas S, Mitrogiannis L, Makrydimas G. The HPV-DNA test in pregnancy: a review of the literature. Cureus. 2023; 15:e38619.

Article15. Kamal M, Topiwala F. Nonneoplastic cervical cytology. Cytojournal. 2022; 19:25.

Article16. Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. Cytology: diagnostic principles and clinical correlates. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2021. 5th.17. Origoni M, Salvatore S, Perino A, Cucinella G, Candiani M. Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) in pregnancy: the state of the art. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014; 18:851–60.18. Grimm D, Lang I, Prieske K, et al. Course of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia diagnosed during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020; 301:1503–12.

Article19. Stuebs FA, Mergel F, Koch MC, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: development during pregnancy and postpartum. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023; 307:1567–72.

Article20. Dasgupta S. The fate of cervical dysplastic lesions during pregnancy and the impact of the delivery mode: a review. Cureus. 2023; 15:e42100.

Article21. Chen C, Xu Y, Huang W, Du Y, Hu C. Natural history of histologically confirmed high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during pregnancy: meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:e048055.

Article22. Ehret A, Bark VN, Mondal A, Fehm TN, Hampl M. Regression rate of high-grade cervical intraepithelial lesions in women younger than 25 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023; 307:981–90.

Article23. Han B, Yuan M, Gong Y, et al. The clinical course of untreated CIN2 (HPV16/18+) under active monitoring: a protocol of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023; 102:e32855.

Article24. Ho GY, Bierman R, Beardsley L, Chang CJ, Burk RD. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338:423–8.

Article25. Ostor AG. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993; 12:186–92.26. Ahdoot D, Van Nostrand KM, Nguyen NJ, et al. The effect of route of delivery on regression of abnormal cervical cytologic findings in the postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 178:1116–20.

Article27. Chung SM, Son GH, Nam EJ, et al. Mode of delivery influences the regression of abnormal cervical cytology. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011; 72:234–8.

Article28. Coppola A, Sorosky J, Casper R, Anderson B, Buller RE. The clinical course of cervical carcinoma in situ diagnosed during pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 1997; 67:162–5.29. Bracic T, Reich O, Taumberger N, Tamussino K, Trutnovsky G. Does mode of delivery impact the course of cervical dysplasia in pregnancy? A review of 219 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022; 274:13–8.

Article30. Cubo-Abert M, Centeno-Mediavilla C, Franco-Zabala P, et al. Risk factors for progression or persistence of squamous intraepithelial lesions diagnosed during pregnancy. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012; 16:34–8.

Article31. Douligeris A, Pergialiotis V, Pappa K, et al. The effect of the delivery mode on the evolution of cervical intraepithelial lesions during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022; 51:102462.

Article32. Frega A, Verrone A, Manzara F, et al. Expression of E6/E7 HPV-DNA, HPV-mRNA and colposcopic features in management of CIN2/3 during pregnancy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016; 20:4236–42.33. Hong DK, Kim SA, Lim KT, Lee KH, Kim TJ, So KA. Clinical outcome of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during pregnancy: a 10-year experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019; 236:173–6.

Article34. Pongsuvareeyakul T, Eaton S, Quddus MR, Sung CJ, Singh K. Comparison of cervical HSIL outcome between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2022; 52:544–55.35. Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP Risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020; 24:102–31.

Article36. Nayar R, Chhieng DC, Crothers B, et al. Moving forward-the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors and beyond: implications and suggestions for laboratories. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020; 9:291–303.

Article37. Larish A, Long ME. Diagnosis and management of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in pregnancy and postpartum. Obstet Gynecol. 2024; 144:328–38.

Article38. Perrone AM, Bovicelli A, D’Andrilli G, Borghese G, Giordano A, De Iaco P. Cervical cancer in pregnancy: analysis of the literature and innovative approaches. J Cell Physiol. 2019; 234:14975–90.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pathological and statistical studies of koilocytosis in the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- Management of gynecologic patients with precancerous disease

- The efficacy of a real-time optoelectronic device as a diagnostic tool of over cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 lesion

- New insights into cervical cancer screening

- Treatment of the patients with abnormal cervical cytology: a "see-and-treat" versus three-step strategy