J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Oct;39(40):e267. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e267.

Estimating Excess Mortality During the COVID-19 Pandemic Between 2020–2022 in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Data Analysis Team, Central Disease Control Headquarters for COVID-19, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Cheongju, Korea

- 2Innovation Center for Industrial Mathematics, National Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Division of Public Health Emergency Response Research, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Cheongju, Korea

- KMID: 2560663

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e267

Abstract

- Background

The persistent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had direct and indirect effects on mortality, making it essential to analyze excess mortality to fully understand the impact of the pandemic. In this study, we constructed a mathematical model using number of deaths from Statistics Korea and analyzed excess mortality between 2020 and 2022 according to age, sex, and dominant severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 variant period.

Methods

Number of all-cause deaths between 2010 and 2022 were obtained from the annual cause-of-death statistics provided by Statistics Korea. COVID-19 mortality data were acquired from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. A multivariate linear regression model with seasonal effect, stratified by sex and age, was used to estimate the number of deaths in the absence of COVID-19. The estimated excess mortality rate was calculated.

Results

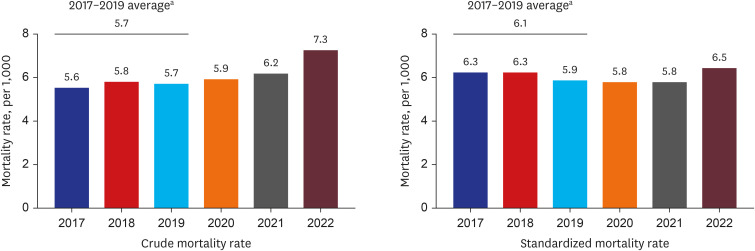

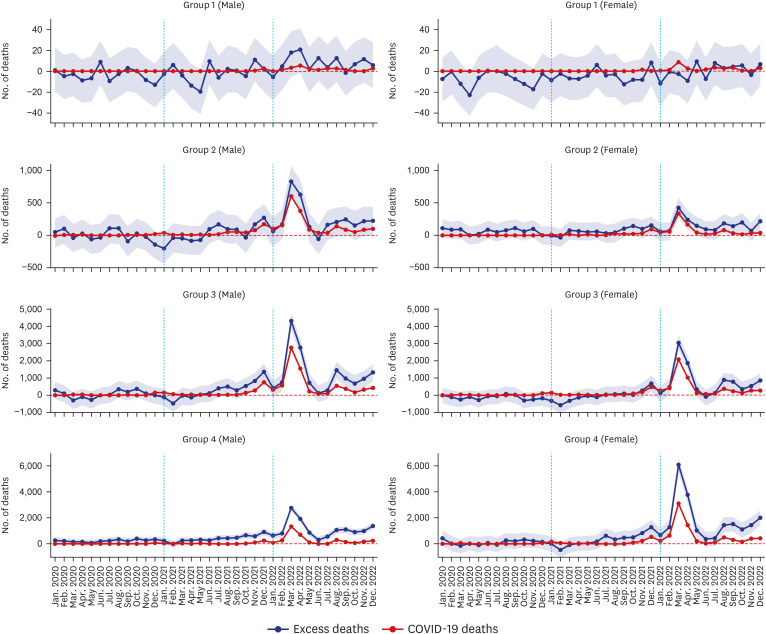

Excess mortality was not significant between January 2020 and October 2021. However, it started to increase monthly from November 2021 and reached its highest point during the omicron-dominant period. Specifically, in March and April 2022, during the omicron BA.1/BA.2-dominant period, the estimated median values for excess mortality were the highest at 17,634 and 11,379, respectively. Both COVID-19-related deaths and excess mortality increased with age. A notable increase in excess mortality was observed in individuals aged ≥ 65 years. In the context of excess mortality per 100,000 population based on the estimated median values in March 2022, the highest numbers were found among males and females aged ≥ 85 years at 1,048 and 910, respectively.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic coupled with its high transmissibility not only increased COVID-19-related deaths but also had a significant impact on overall mortality rates, especially in the elderly. Therefore, it is crucial to concentrate healthcare resources and services on the elderly and ensure continued access to healthcare services during pandemics. Establishing an excess mortality monitoring system in the early stages of a pandemic is necessary to understand the impact of infectious diseases on mortality and effectively evaluate pandemic response policies.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic .2. World Health Organization. COVID-19 dashboard. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c .3. Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020; 78:185–193. PMID: 32305533.4. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency press release. Updated September 7, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501010000&bid=0015&list_no=723415&code=&act=view&nPage=9 .5. Msemburi W, Karlinsky A, Knutson V, Aleshin-Guendel S, Chatterji S, Wakefield J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature. 2023; 613(7942):130–137. PMID: 36517599.6. Garber AM. Learning from excess pandemic deaths. JAMA. 2021; 325(17):1729.7. Kang E, Yun J, Hwang SH, Lee H, Lee JY. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the healthcare utilization in Korea: analysis of a nationwide survey. J Infect Public Health. 2022; 15(8):915–921. PMID: 35872432.8. Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, Purushotham A, Nolte E, Sullivan R, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020; 21(8):1023–1034. PMID: 32702310.9. Checchi F, Roberts L. Interpreting and using mortality data in humanitarian emergencies: a primer for non-epidemiologists. Updated 2005. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://odihpn.org/wp-content/uploads/2005/09/networkpaper052.pdf .10. Beaney T, Clarke JM, Jain V, Golestaneh AK, Lyons G, Salman D, et al. Excess mortality: the gold standard in measuring the impact of COVID-19 worldwide? J R Soc Med. 2020; 113(9):329–334. PMID: 32910871.11. Statistics Korea. Excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated 2021. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://kosis.kr/covid/statistics_excessdeath.do .12. Oh J, Lee JK, Schwarz D, Ratcliffe HL, Markuns JF, Hirschhorn LR. National response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Syst Reform. 2020; 6(1):e1753464. PMID: 32347772.13. The Government of the Republic of Korea. All about Korea’s response to COVID-19. Updated 2020. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/brd/m_22742/view.do?seq=35&srchFr=&%3BsrchTo=&%3BsrchWord=&%3BsrchTp=&%3Bmulti_itm_seq=0&%3Bitm_seq_1=0&%3Bitm_seq_2=0&%3Bcompany_cd=&%3Bcompany_nm=&page=2&titleNm= .14. Majeed A, Seo Y, Heo K, Lee D. Can the UK emulate the South Korean approach to covid-19? BMJ. 2020; 369:m2084. PMID: 32467112.15. Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ, Klimkin I, Kawachi I, Irizarry RA, et al. Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ. 2021; 373(1137):n1137. PMID: 34011491.16. Shin MS, Sim B, Jang WM, Lee JY. Estimation of excess all-cause mortality during COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(39):e280. PMID: 34636505.17. Oh J, Min J, Kang C, Kim E, Lee JP, Kim H, et al. Excess mortality and the COVID-19 pandemic: causes of death and social inequalities. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):2293. PMID: 36476143.18. Han C, Jang H, Oh J. Excess mortality during the coronavirus disease pandemic in Korea. BMC Public Health. 2023; 23(1):1698. PMID: 37660007.19. Butt AA, Dargham SR, Coyle P, Yassine HM, Al-Khal A, Abou-Samra AB, et al. COVID-19 disease severity in persons infected with omicron BA.1 and BA.2 sublineages and association with vaccination status. JAMA Intern Med. 2022; 182(10):1097–1099. PMID: 35994264.20. Ciuffreda L, Lorenzo-Salazar JM, García-Martínez de Artola D, Gil-Campesino H, Alcoba-Florez J, Rodríguez-Pérez H, et al. Reinfection rate and disease severity of the BA.5 omicron SARS-CoV-2 lineage compared to previously circulating variants of concern in the Canary Islands (Spain). Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023; 12(1):2202281. PMID: 37039029.21. Sheikh A, Kerr S, Woolhouse M, McMenamin J, Robertson C. EAVE II Collaborators. Severity of omicron variant of concern and effectiveness of vaccine boosters against symptomatic disease in Scotland (EAVE II): a national cohort study with nested test-negative design. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022; 22(7):959–966. PMID: 35468332.22. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Severity of COVID-19 associated with SARS-CoV-2 variants dominant period in the Republic of Korea. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2023; 16(43):1464–1487.23. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Response and Management Guidelines for Local Governments in South Korea. 13-3rd ed. Cheongju, Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2023.24. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act. Updated 2023. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2&query=INFECTIOUS%20DISEASE%20CONTROL%20AND%20PREVENTION%20ACT#liBgcolor1 .25. Aron J, Muellbauer J, Giattino C, Ritchie H. A pandemic primer on excess mortality statistics and their comparability across countries. Updated 2020. Accessed on May 1 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-excess-mortality .26. Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(18):1757–1766. PMID: 32329974.27. Filip R, Gheorghita Puscaselu R, Anchidin-Norocel L, Dimian M, Savage WK. Global challenges to public health care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of pandemic measures and problems. J Pers Med. 2022; 12(8):1295. PMID: 36013244.28. Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, Hall G, Denaxas S, Chang WH, et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(11):e043828.29. Kiang MV, Irizarry RA, Buckee CO, Balsari S. Every body counts: measuring mortality from the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173(12):1004–1007. PMID: 32915654.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Excess mortality in older adults and cumulative excess mortality across all ages during the COVID-19 pandemic in the 20 countries with the highest mortality rates worldwide

- Excess Deaths in Korea During the COVID-19 Pandemic: 2020-2022

- The epidemiologic characteristics of dog-bite injury during COVID-19 pandemic in Korea

- Age-Related Morbidity and Mortality among Patients with COVID-19

- Estimation of Excess All-cause Mortality during COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea