J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Nov;39(42):e310. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e310.

Rescue Cerclage in Women With Acute Cervical Insufficiency and IntraAmniotic Inflammation: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea

- KMID: 2560621

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e310

Abstract

- Background

To assess the effectiveness of rescue cerclage concerning pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women with acute cervical insufficiency (CI) complicated with intraamniotic inflammation (IAI) compared with those managed expectantly.

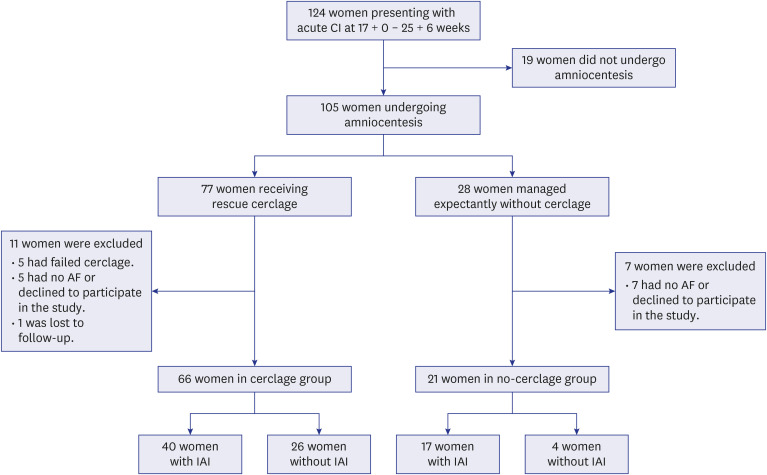

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included 87 consecutive singleton pregnant women (17–25 weeks) with acute CI who underwent amniocentesis to assess IAI. Amniotic fluid (AF) samples were assayed for interleukin-6 to define IAI (≥ 2.6 ng/mL). Primary and secondary outcomes were assessed in a subset of CI patients with IAI. The primary outcome measures were spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) at < 28 and < 34 weeks, and the secondary outcomes were interval from sampling to delivery, neonatal survival, neonatal birth weight, and histologic and clinical chorioamnionitis. Macrolide antibiotics were prescribed depending on the type of microorganism isolated from the AF, clinically suspected IAI, and the discretion of the attending clinician.

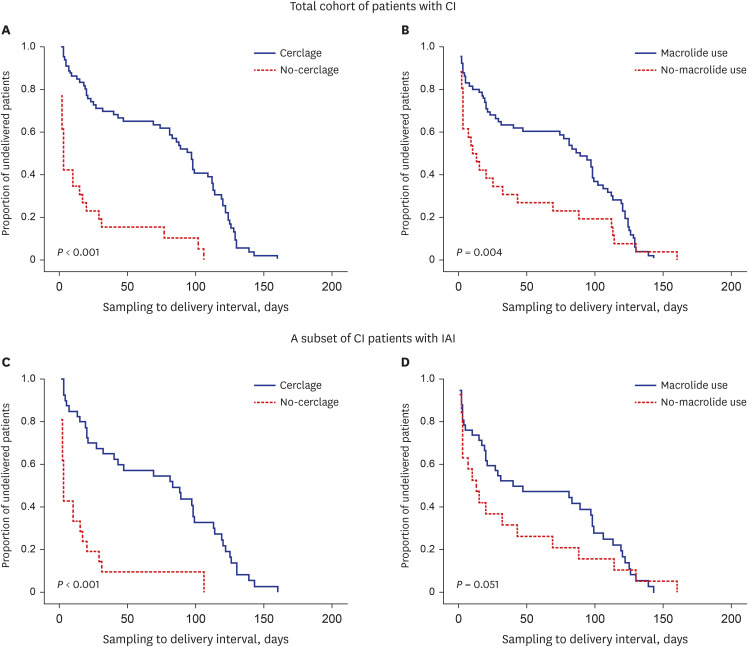

Results

IAI was identified in 65.5% (57/87) of patients with CI, of whom 73.6% (42/57) were treated with macrolide antibiotics. Among the CI patients with IAI (n = 57), 40 underwent rescue cerclage and 17 were expectantly managed. The rates of SPTBs at < 28 and < 34 weeks were significantly lower and the latency period was significantly longer in the cerclage group than in the group that was managed expectantly. The median birth weight and neonatal survival rate were significantly higher in the cerclage group than in the group that was managed expectantly. However, the rates of histologic and clinical chorioamnionitis did not differ between the groups. Multivariable analyses revealed that rescue cerclage placement and administration of macrolide antibiotics were significantly associated with a decrease in SPTBs at < 28 and < 34 weeks, prolonged gestational latency, and increased likelihood of neonatal survival, after adjusting for possible confounding parameters; however, macrolide antibiotic administration did not reach statistical significance with respect to SPTB at < 34 weeks and neonatal survival (P = 0.076 and 0.063, respectively).

Conclusion

Rescue cerclage along with macrolide antibiotic treatment may positively impact pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women with CI complicated by IAI, compared with expectant management. These findings suggest the benefit of cerclage placement even in patients with CI complicated by IAI.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lidegaard O. Cervical incompetence and cerclage in Denmark 1980-1990. A register based epidemiological survey. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994; 73(1):35–38. PMID: 8304022.2. ACOG practice bulletin No.142: cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 123(2 Pt 1):372–379. PMID: 24451674.3. Iams JD, Johnson FF, Sonek J, Sachs L, Gebauer C, Samuels P. Cervical competence as a continuum: a study of ultrasonographic cervical length and obstetric performance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 172(4 Pt 1):1097–1103. PMID: 7726247.4. Romero R, Gonzalez R, Sepulveda W, Brandt F, Ramirez M, Sorokin Y, et al. Infection and labor. VIII. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in patients with suspected cervical incompetence: prevalence and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 167(4 Pt 1):1086–1091. PMID: 1415396.5. Lee SE, Romero R, Park CW, Jun JK, Yoon BH. The frequency and significance of intraamniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198(6):633.e1–633.e8.6. Lee SM, Park KH, Jung EY, Cho SH, Ryu A. Prediction of spontaneous preterm birth in women with cervical insufficiency: comprehensive analysis of multiple proteins in amniotic fluid. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016; 42(7):776–783. PMID: 26990253.7. Lee KN, Park KH, Kim YM, Cho I, Kim TE. Prediction of emergency cerclage outcomes in women with cervical insufficiency: the role of inflammatory, angiogenic, and extracellular matrix-related proteins in amniotic fluid. PLoS One. 2022; 17(5):e0268291. PMID: 35536791.8. Chalupska M, Kacerovsky M, Stranik J, Gregor M, Maly J, Jacobsson B, et al. Intra-amniotic infection and sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in cervical insufficiency with prolapsed fetal membranes: clinical implications. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2021; 48(1):58–69. PMID: 33291113.9. Kim YM, Park KH, Park H, Yoo HN, Kook SY, Jeon SJ. Complement C3a, but not C5a, levels in amniotic fluid are associated with intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation and preterm delivery in women with cervical insufficiency or an asymptomatic short cervix (≤ 25 mm). J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33(35):e220. PMID: 30140190.10. Park H, Hong S, Yoo HN, Kim YM, Lee SJ, Park KH. The identification of immune-related plasma proteins associated with spontaneous preterm delivery and intra-amniotic infection in women with premature cervical dilation or an asymptomatic short cervix. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(7):e26. PMID: 32080985.11. Chatzakis C, Efthymiou A, Sotiriadis A, Makrydimas G. Emergency cerclage in singleton pregnancies with painless cervical dilatation: a meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020; 99(11):1444–1457. PMID: 32757297.12. Ehsanipoor RM, Seligman NS, Saccone G, Szymanski LM, Wissinger C, Werner EF, et al. Physical examination-indicated cerclage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126(1):125–135. PMID: 26241265.13. Wei Y, Wang S. Comparison of emergency cervical cerclage and expectant treatment in cervical insufficiency in singleton pregnancy: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023; 18(2):e0278342. PMID: 36827361.14. Berghella V, Ludmir J, Simonazzi G, Owen J. Transvaginal cervical cerclage: evidence for perioperative management strategies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 209(3):181–192. PMID: 23416155.15. Mays JK, Figueroa R, Shah J, Khakoo H, Kaminsky S, Tejani N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 95(5):652–655. PMID: 10775723.16. Diago Almela VJ, Martinez-Varea A, Perales-Puchalt A, Alonso-Diaz R, Perales A. Good prognosis of cerclage in cases of cervical insufficiency when intra-amniotic inflammation/infection is ruled out. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015; 28(13):1563–1568. PMID: 25212978.17. Aguin E, Aguin T, Cordoba M, Aguin V, Roberts R, Albayrak S, et al. Amniotic fluid inflammation with negative culture and outcome after cervical cerclage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012; 25(10):1990–1994. PMID: 22372938.18. Mönckeberg M, Valdés R, Kusanovic JP, Schepeler M, Nien JK, Pertossi E, et al. Patients with acute cervical insufficiency without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation treated with cerclage have a good prognosis. J Perinat Med. 2019; 47(5):500–509. PMID: 30849048.19. Jung EY, Park KH, Lee SY, Ryu A, Oh KJ. Non-invasive prediction of intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency or an asymptomatic short cervix (≤15 mm). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015; 292(3):579–587. PMID: 25762201.20. Oh KJ, Romero R, Park JY, Lee J, Conde-Agudelo A, Hong JS, et al. Evidence that antibiotic administration is effective in the treatment of a subset of patients with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation presenting with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 221(2):140.e1–140.e18.21. Premkumar A, Sinha N, Miller ES, Peaceman AM. Perioperative use of cefazolin and indomethacin for physical examination-indicated cerclages to improve gestational latency. Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 135(6):1409–1416. PMID: 32459433.22. Daskalakis G, Papantoniou N, Mesogitis S, Antsaklis A. Management of cervical insufficiency and bulging fetal membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107(2 Pt 1):221–226. PMID: 16449104.23. Althuisius SM, Dekker GA, Hummel P, van Geijn HP. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial: emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 189(4):907–910. PMID: 14586323.24. Pereira L, Cotter A, Gómez R, Berghella V, Prasertcharoensuk W, Rasanen J, et al. Expectant management compared with physical examination-indicated cerclage (EM-PEC) in selected women with a dilated cervix at 14(0/7)-25(6/7) weeks: results from the EM-PEC international cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 197(5):483.e1–483.e8.25. Park KH, Kim SN, Oh KJ, Lee SY, Jeong EH, Ryu A. Noninvasive prediction of intra-amniotic infection and/or inflammation in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Reprod Sci. 2012; 19(6):658–665. PMID: 22457430.26. Jung EY, Choi BY, Rhee J, Park J, Cho SH, Park KH. Relation between amniotic fluid infection or cytokine levels and hearing screen failure in infants at 32 wk gestation or less. Pediatr Res. 2017; 81(2):349–355. PMID: 27925622.27. Lee JY, Park KH, Kim A, Yang HR, Jung EY, Cho SH. Maternal and placental risk factors for developing necrotizing enterocolitis in very preterm infants. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017; 58(1):57–62. PMID: 27328638.28. Lee SY, Park KH, Jeong EH, Oh KJ, Ryu A, Kim A. Intra-amniotic infection/inflammation as a risk factor for subsequent ruptured membranes after clinically indicated amniocentesis in preterm labor. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28(8):1226–1232. PMID: 23960452.29. Yoo HN, Park KH, Jung EY, Kim YM, Kook SY, Jeon SJ. Non-invasive prediction of preterm birth in women with cervical insufficiency or an asymptomatic short cervix (≤25 mm) by measurement of biomarkers in the cervicovaginal fluid. PLoS One. 2017; 12(7):e0180878. PMID: 28700733.30. Kim SY, Park KH, Kim HJ, Kim YM, Ahn K, Lee KN. Inflammation-related immune proteins in maternal plasma as potential predictive biomarkers for rescue cerclage outcome in women with cervical insufficiency. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2022; 88(1):e13557. PMID: 35499384.31. Romero R, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Gomez R, Diamond MP, Kenney JS, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic value of amniotic fluid white blood cell count, glucose, interleukin-6, and gram stain in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 169(4):805–816. PMID: 7694461.32. Yoon BH, Yang SH, Jun JK, Park KH, Kim CJ, Romero R. Maternal blood C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, and temperature in preterm labor: a comparison with amniotic fluid white blood cell count. Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 87(2):231–237. PMID: 8559530.33. Gibbs RS, Blanco JD, St Clair PJ, Castaneda YS. Quantitative bacteriology of amniotic fluid from women with clinical intraamniotic infection at term. J Infect Dis. 1982; 145(1):1–8. PMID: 7033397.34. Terkildsen MF, Parilla BV, Kumar P, Grobman WA. Factors associated with success of emergent second-trimester cerclage. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 101(3):565–569. PMID: 12636963.35. Fuchs F, Senat MV, Fernandez H, Gervaise A, Frydman R, Bouyer J. Predictive score for early preterm birth in decisions about emergency cervical cerclage in singleton pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012; 91(6):744–749. PMID: 22375688.36. Namouz S, Porat S, Okun N, Windrim R, Farine D. Emergency cerclage: literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2013; 68(5):379–388. PMID: 23624963.37. Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, Pieterse ME, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM. Time-varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann Transl Med. 2018; 6(7):121. PMID: 29955581.38. Verlato G, Marrelli D, Accordini S, Bencivenga M, Di Leo A, Marchet A, et al. Short-term and long-term risk factors in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21(21):6434–6443. PMID: 26074682.39. Kragh Andersen P, Pohar Perme M, van Houwelingen HC, Cook RJ, Joly P, Martinussen T, et al. Analysis of time-to-event for observational studies: guidance to the use of intensity models. Stat Med. 2021; 40(1):185–211. PMID: 33043497.40. Jung EY, Park KH, Lee SY, Ryu A, Joo JK, Park JW. Predicting outcomes of emergency cerclage in women with cervical insufficiency using inflammatory markers in maternal blood and amniotic fluid. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016; 132(2):165–169. PMID: 26553528.41. Park JC, Kim DJ, Kwak-Kim J. Upregulated amniotic fluid cytokines and chemokines in emergency cerclage with protruding membranes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011; 66(4):310–319. PMID: 21410810.42. Kiefer DG, Peltier MR, Keeler SM, Rust O, Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM, et al. Efficacy of midtrimester short cervix interventions is conditional on intraamniotic inflammation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 214(2):276.e1–276.e6.43. Monsanto SP, Daher S, Ono E, Pendeloski KPT, Traina E, Mattar R, et al. Cervical cerclage placement decreases local levels of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 217(4):455.e1–455.e8.44. Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Espinoza J. Micronutrients and intrauterine infection, preterm birth and the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. J Nutr. 2003; 133(5):Suppl 2. 1668S–1673S. PMID: 12730483.45. Rehewy MS, Jaszczak S, Hafez ES, Thomas A, Brown WJ. Ureaplasma urealyticum (T-mycoplasma) in vaginal fluid and cervical mucus from fertile and infertile women. Fertil Steril. 1978; 30(3):297–300. PMID: 568567.46. Horváth B, Turay A, Lakatos F, Végh G, Illei G. Incidence of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum infection in pregnant women and gynaecological patients; the effectivity of doxycycline therapy. Ther Hung. 1989; 37(1):23–27. PMID: 2756511.47. Ahrens P, Andersen LO, Lilje B, Johannesen TB, Dahl EG, Baig S, et al. Changes in the vaginal microbiota following antibiotic treatment for Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One. 2020; 15(7):e0236036. PMID: 32722712.48. Witt A, Sommer EM, Cichna M, Postlbauer K, Widhalm A, Gregor H, et al. Placental passage of clarithromycin surpasses other macrolide antibiotics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 188(3):816–819. PMID: 12634663.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Recent Management of Cervical incompetence

- Emergency cervical cerclage in advanced cervical incompetence

- Emergency cerclage in cervical incompetence

- A Case of Successful Transabdominal Cervicoisthimic Cerclage in a Patient with Incompetent Internal as of Cervix

- Emergency Cervical Cerclage: A Retrospective Study of 5 Years' Practice in 71 Cases